Should voting (or actively abstaining) be compulsory?

- Published

Nearly 16 million registered voters did not turn out at the 2010 general election

In less than four months' time, Britain will go to the polls in what promises to be a tense and highly unpredictable general election. Politicians and campaigners are gearing up and there is already much excitement - in the Westminster village, at least.

But as with previous UK elections, millions of voters are expected not to turn out and many more will not be registered to vote in the first place. In 2010, a close election, the turnout was 65%; nearly 16 million registered electors did not vote. And recent estimates suggest 7.5 million eligible voters are not able to vote because they are either missing from the electoral register or not correctly entered on it.

The right to vote is the most fundamental tenet of democracy and yet millions do not exercise it. So should that right be made into a duty?

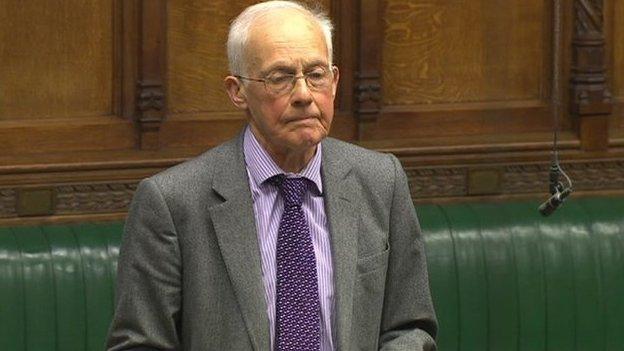

The senior Labour backbencher, David Winnick, MP for Walsall, is one of a number of politicians supporting more radical moves to get people voting.

Labour MP David Winnick is calling for voting to be made a "civic duty"

He has introduced a Commons ten minute rule bill - an opportunity to highlight an issue of concern - suggesting that voting should become a "civic duty".

Mr Winnick pointed out that, at the last general election, "those who did not vote were larger in number than those who voted for any one of the political parties contesting the election".

"If you add that figure to those not correctly registered that adds up to more than the votes for the two main parties in the election," he told MPs.

"I would have thought that should be a matter of much and serious concern to this House whether or not what I am proposing is accepted.

"If we want our democracy to flourish, commonsense dictates we should do what we can to get far more people to participate in elections than do at the moment."

Mr Winnick wants the UK to consider a system similar to that in Australia, where people who do not vote, or at least express their intention to abstain, are fined.

He insists his proposals do not constitute compulsory voting as such. Those who have religious or other objections would be able abstain but they would be required to register their abstention by contacting their electoral office in advance or doing so in person at the polling station.

However, Mr Winnick's vision does represent a radical move from the voluntary principle on which the British system has been based since universal suffrage was introduced nearly a century ago.

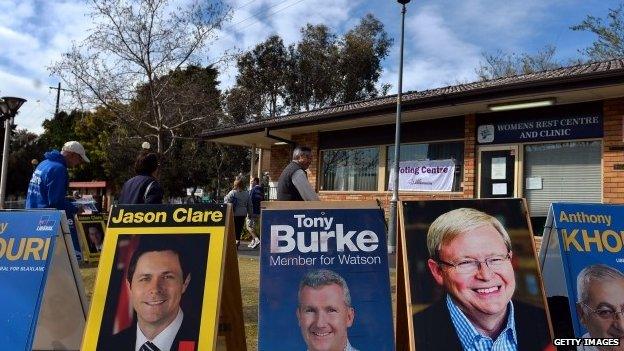

Turnout in Australia's 2013 general election was 93%

Australia's voting system

Registering to vote and going to the polls have been legal duties in Australia for citizens aged 18 and over since 1924.

Failing to vote can result in a fine of 20 Australian dollars - around £11 - and court action if fines are not paid.

Supporters say Australia boasts one of the highest levels of civic participation in the world.

Critics say a high turnout based on a mandatory system does not translate into a politically engaged electorate.

There have been several failed attempts to abolish the system.

Australia is one of only 11 countries which enforce participation in elections. Around a dozen more have adopted some kind of mandatory voting legislation but do not enforce it.

But the idea of enforcing civic duty such as jury or military service is established in democracies around the world.

The US, for example, has written certain civic obligations into the constitution - though it does not have mandatory voting.

Supporters of greater enforcement of voting such as David Winnick ask why participation in elections should not be seen as a similar obligation of the citizen towards the state.

"Don't we all have obligations?," asked Mr Winnick.

"We all have to pay local and national taxes and if we drive we pay road tax...we can't opt out and we don't want anyone to opt out. Is that an infringement of civil liberties?"

"I don't see why it should be argued that if there is a civic obligation to vote and being able to abstain there should be attack on the grounds that our civil liberties are being undermined."

But critics say such an idea is alien to British democracy with its unwritten constitution and its more ad-hoc approach towards the concept of citizenship.

In a report on voter engagement , externalin November, MPs on the cross-party Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee considered both sides of the argument.

The committee cited evidence that a mandatory system "would be politically very difficult to introduce in a country where it has no precedent" but also heard arguments in favour, including claims that inequality would be reduced through re-engaging disenfranchised communities.

The MPs were split but agreed to recommend a government assessment of how compulsory voting could work in the UK - a move hailed by the Labour MP chairing the committee, Graham Allen, a supporter, as a major step forward.

Some researchers suggest first-time voters should be compelled to take part in elections

"Our democracy is facing a crisis if we do not take urgent action to make elections more accessible to the public and convince them that it is worth voting," he said.

Mr Allen and fellow campaigners are particularly concerned about young people's disengagement with politics and democracy. Only 44% of 18-24 year olds voted in the 2010 general election and research suggests the gap between younger and older age groups in relation to participation in voting is widening.

The Institute for Public Policy Research, a centre-left think tank, highlighting a "dramatic social class divide in electoral participation", has advocated compelling first-time voters to turn out to try to "kick-start voting as a habit of a life-time", with the proviso that the option of "none of the above" should be available on the ballot paper.

Mathew Lawrence, research fellow at the IPPR ,said: "The state already requires people to do much more onerous things than to turn up at a polling station.

"At the moment, politicians can get away with not addressing issues affecting young people because they know that young people are less likely to vote. Why not reverse that and open up a whole section of the electorate? It would force politicians to have a conversation about the interests of young people."

But Mr Lawrence acknowledges British political culture is resistant to such ideas. "We need to find a way of changing the language and the way we present these thoughts; any suggestion of compulsion is very unpopular in Britain. One way round this would be to wrap up a law about voting and participation into a whole constitutional re-think about what it means to be a citizen of the UK in this globalised world."

Others considering the disengagement problem are highly sceptical of any moves to increase the role of the state.

Daniel Bentley, communications director at the Civitas think tank, says: "The problem with compulsory voting is that it does not promote real democratic engagement but just turns voting into one more thing that the state requires us to do, like filling in a tax form or taking the car for its MOT.

"We need people not simply to tick a box on polling day but to be as engaged as possible with decision-making, because that is the only way of ensuring our representatives work for the common good."

Self-styled revolutionary Russell Brand claims there is no point in voting

The government remains wary of any form of compulsory voting and none of the main political parties at Westminster has adopted it as a policy.

Registering to vote is slightly different - under a new system introduced by the coalition government, voters are now required to register individually rather than via the head of a household. A "small civil penalty" of £80 may be imposed on those who "refuse repeated invitations to register".

Meanwhile, campaigners for the option of "none of the above" to be included on ballot papers are continuing to make their case that conscious abstention is better than no participation at all in the democratic process.

Historically Britain has a tradition of resistance to radical reforms to the constitution. But campaigners say dramatic solutions may be required to tackle what is often described as a democratic crisis.

Critics question whether changes to mechanics of the voting system will address this crisis.

Some go as far as to reject the whole system of representative democracy, such as the comedian, campaigner and self-styled revolutionary Russell Brand, who says he's never voted and doesn't see any point in doing so in the future.

"It is not that I am not voting out of apathy," he famously said in a Newsnight interview with Jeremy Paxman.

"I am not voting out of absolute indifference and weariness and exhaustion from the lies, treachery and deceit of the political class that has been going on for generations."

Elections: Compulsory voting on UK polling days?

Daniel Bentley, of Civitas, says society has to find ways to show how voting makes a difference to people's lives.

"The main obstacle to higher turnout is the feeling that there is very little choice on offer - the main parties are fighting over such a narrow strip of territory, and are focusing their efforts on such a small number of swing voters - that voting won't change anything. The rise of parties like UKIP and the Greens, filling some of the space vacated by the three main parties, is a symptom of that.

"The same is true at a local level, where council turnouts are pitiful, but there it is because town halls are not felt to have any real influence over people's day-to-day lives because they don't have enough clout."

Mr Bentley suggests radical devolution to local communities, including of taxation, could be one way of encouraging active citizenship.

There will be a strong interest from all parties in turnout at this year's general election. Another figure seen as worrying low would give fuel to those who say our democracy is broken and to those who recommend radical solutions to fix it.

- Published27 August 2013

- Published22 May 2014