Uncanny political parallels with 1974

- Published

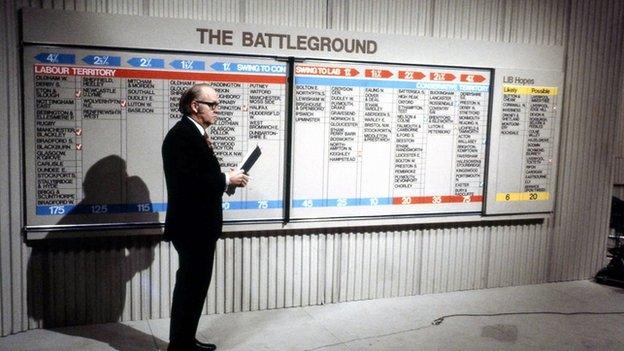

Much horse trading surrounded the February 1974 election

Both major political parties in Britain are profoundly unpopular with the electorate and their leaders regarded with some suspicion.

The outcome of the forthcoming general election is, in consequence, highly uncertain and there is much talk of coalition and of the potential political pulling power of various previously unconsidered minor parties.

The Scottish National Party is riding high and the Ulster Unionists have a new spring in their step because they know they need to be taken seriously.

The domestic economy is in deep trouble and the word "austerity" is on many lips.

There is widespread discussion of oil prices and concern about the fact that first-time buyers are being priced out of the housing market.

Legislation is proposed to curb the power of the trades unions.

The question of Britain's future in Europe is of primary political importance in the election, as is the prospect of our membership terms being renegotiated and then subject to a referendum.

Sounds like the agenda for the general election, just weeks away on 7 May?

Well, yes, although the wary may have spotted some obvious missing issues from the description of our current state of play.

The truth is that my above description of the state of British politics is actually that of the run-up to the first, external of the two general elections of 1974.

Heath's gambit

Then Edward Heath, as Conservative prime minister, propelled the country to the polling stations in February to answer the question: "Who governs Britain?" only to be rewarded with the answer: "We're not entirely sure, mate, but not you."

Edward Heath was expected to win in 1974

It was nightfall on 4 March 1974, and I was walking across Parliament Square towards Whitehall when I heard the cheers ringing and saw the flash-bulbs crackling into the blue-black sky from the direction of Downing Street.

It was four days after the election and the excitement heralded Harold Wilson's surprise return to office.

February 1974 Election: In Numbers:

Labour: Seats won: 301, up 20. Share of vote: 37.2%

Conservative: Seats won: 297, down 37. Share of vote: 37.9%

Liberal: Seats won: 14, up eight. Share of vote: 19.3%

Turnout: 78.8%

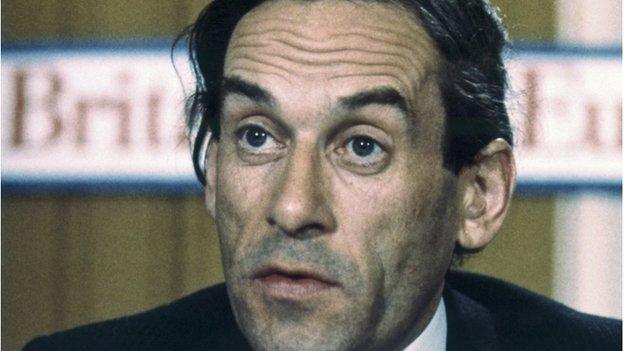

Over the previous weekend, Heath had remained in post, as the prime minister is constitutionally obliged to do, while trying unsuccessfully to form a coalition government with the Liberal Party which had enjoyed a hugely successful popular vote of six million, albeit only translating into 14 seats.

Their leader, Jeremy Thorpe, had been negotiating the post of Home Secretary for himself, but the Liberal Party executive put the kibosh on any coalition with the Tories in favour of a proposed Government of National Unity to sort out the country's myriad problems.

It was comprehensively rejected.

That led to Wilson's assumption of office as a minority prime minister and the inevitable second general election, the following October, which gave him a narrow overall majority of three.

What we have learned recently, as a result of Thorpe's death and the publication of much material that could not previously be printed, but most certainly didn't know then, was that the unconventional nature of the Liberal leader's private life, including allegations of homosexuality, was known in Whitehall - and to Wilson.

It would have been difficult, at the very least, for Thorpe to have become Home Secretary in such circumstances as his subsequent trial and acquittal on charges of conspiracy to murder would make only too clear.

Minority government

We knew little of any of that then, but we were to learn much in the coming years of what minority - or sliver-thin majority - government can mean in comparison to coalition.

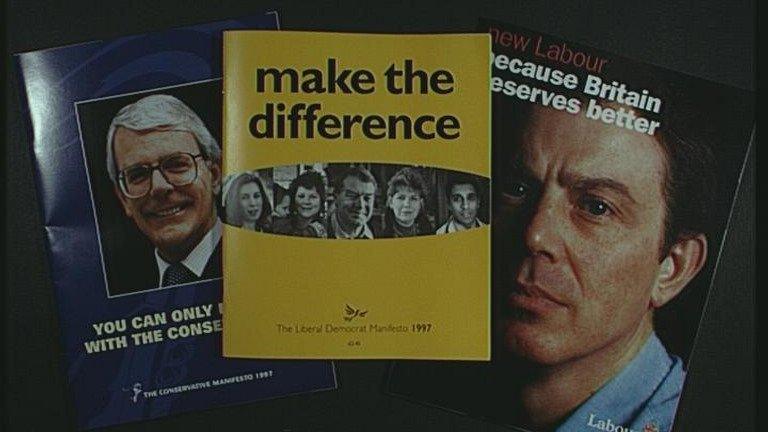

Since the Rose Garden accord between the Tories and the Liberal Democrats in 2010, the country in general and Nick Clegg in particular, has learned the price of coalition.

It has meant that the majority party has had things most of its own way and, from their point of view, the Lib Dems could go hang.

Nick Clegg may hum "it's my party and I'll cry if I want to" in the privacy of his morning shower and well he might; the opinion polls indicate that his party may lose , externalat least half of its Westminster seats in May, including possibly his own, which has been targeted, external by Labour.

That is a kind interpretation: the bald statistics indicate something even worse.

Their actual level of support in the polls, which has consistently been about 7%, equivalent to that of the Green Party, would mean that they would only win a small handful of seats were it not for the individual personal reputations of many of their 56 MPs.

Perhaps in 2010 Clegg should have considered the words of Harold Wilson, reverberating down the years when Heath, in the interim between the two 1974 elections, again proposed some sort of national coalition.

Wilson retorted: "Coalition would mean Con policies, Con leadership by a Con party for a con-trick."

It was, he said, a "desperate attempt by desperate men to get back into power by any means." (Note the gender specific which would never happen today).

Knife edge

The Wilson and Callaghan governments of 40 years ago lasted five years but provided enough news for a political generation.

They lived on a knife-edge, and so did we, up above in the press gallery.

The limited nature of the government's majority did not inhibit its choice of controversial legislation which made for endless nail-biting news.

Jeremy Thorpe hoped to serve in Cabinet

The 1975 referendum on Europe, replayed as it is today with extraordinary similarities, could well have brought down the government had Wilson as prime minister not allowed his dissident ministers the right to express their dissent.

The curiosity is, of course, that in those days being in favour of Europe was the right-on Establishment case.

It was only wild lefties who thought otherwise.

Try asking any elderly Tories now how they voted in 1975 and they will cough and hurrumph and say, well of course they didn't realise what was involved.

These are the people who UKIP have recognised as potential voters, and beside them the southern white working class, and those people in the north who feel disenfranchised by the nature of politics and the collapse of Labour's traditional voter base.

Add to this pot pourri, the Lib Dems' failure to offer any sort of alternative, the enthusiastic emergence of the Scottish Nationalists in the wake of their narrowly-defeated shot at independence, the Democratic Unionist's recognition of the power of their block vote, the Green Party's surprising emergence as a really different choice and we have a recipe for re-running the politics of the 1970s.

Feelings ran high during the campaign

We may have a minority government of either stripe.

We may have a coalition of unpredictable partners.

We may have a government with a narrow majority which will then be obliged to compromise.

What we know now, however, particularly since the events in Paris in recent weeks, is that important differences may well be imposed on our politics because of the extent to which terrorism has changed - and will undoubtedly continue to change - our world.

In uncertain times the electorate will seek certainty from the government.

That is something which may, unexpectedly, put a powerful card in the hand of David Cameron as the sitting prime minister.

- Published20 January 2015

- Published25 February 2015

- Published4 March 2014