Budget 2015: A brief history of pre-election Budgets

- Published

George Osborne will deliver his sixth Budget as Chancellor on Wednesday, 50 days before the General Election.

He has pledged no "gimmicks" but newspaper reports have suggested he is considering tax cuts and could have as much as £5bn for a pre-election "giveaway".

Pre-election Budgets are invariably controversial with many entering political folklore, although former Chancellor Ken Clarke has claimed that no Budgets "in living memory" have changed the outcome of a subsequent election.

How have some of Mr Osborne's predecessors dealt with the twin pressures of securing the nation's finances while trying to deliver their party an election victory?

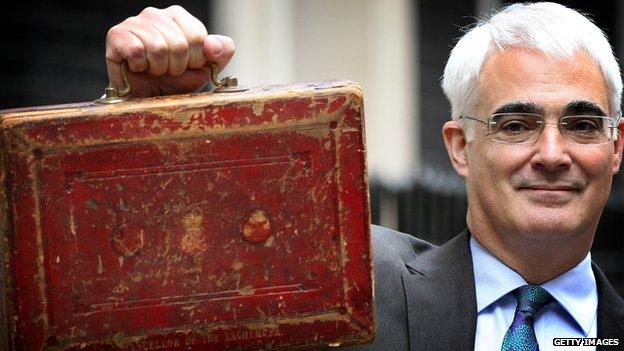

2010: Alistair Darling (24 March)

What was announced: In the run-up to his third Budget, Mr Darling ruled out any pre-election giveaways, saying his package would be "sensible and workmanlike".

With the UK having recently emerged from recession and with the annual budget deficit running well in excess of £150bn, Mr Darling said his priorities were to get borrowing down and secure the economic recovery.

He announced plans for a number of tax rises on the better-off, saying he would curb personal tax allowances for those earning more than £150,000.

With one eye on May's election, he vowed to phase in planned rises in fuel duty, promised an extra £600m for winter fuel allowance and offered to suspend stamp duty on home purchases by first-time buyers of up to £250,000.

Among the more eye-catching proposals was a planned 10% rise in duty on cider.

There was no increase in VAT despite speculation in advance that it had been considered and rumours of a disagreement between Mr Darling and then Prime Minister Gordon Brown.

What happened next? Mr Darling stood down as chancellor five days after the general election when the Conservatives and Lib Dems formed a coalition government, although he remained as shadow chancellor for a further five months.

In his "emergency" Budget in June, the new chancellor George Osborne reversed some of his predecessor's measures, including the 10% tax on cider - although Labour had already effectively ditched the plan due to opposition.

However some other measures in Mr Darling's Budget - including a four-year freeze on inheritance tax thresholds - survived the change of government.

Mr Osborne also chose not to reverse a rise in the top rate of tax from 40p to 50p, announced by Mr Darling in 2009 but which only came into force in April 2010.

The main announcement in Mr Osborne's first Budget was a rise in VAT from 17.5% to 20%, something Labour had flirted with but decided against a few months earlier.

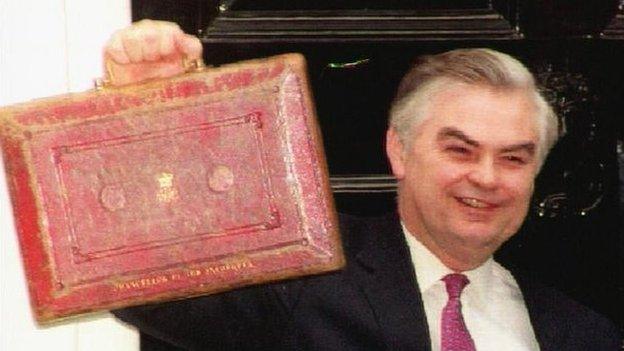

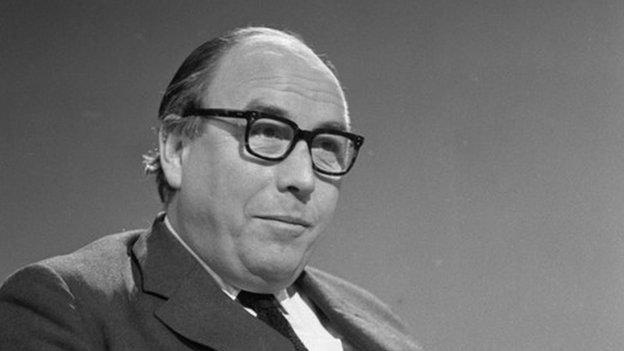

1996: Ken Clarke (26 November)

What was announced: Although the 1997 general election was held in May, the Conservatives - trailing Labour badly in the polls at the time - opted to announce their final Budget nearly six months earlier, at the end of November 1996.

In his speech, Chancellor Kenneth Clarke said the UK was experiencing a "Rolls-Royce recovery - built to last" and predicted economic growth of 3.5% in 1997.

He cut the basic level of income tax from 24p to 23p and raised inheritance tax thresholds to £215,000.

Mr Clarke, the last Chancellor to sip alcohol during his Budget address, reduced duty on spirits but announced a 40% increase on tax on so-called alcopops.

What happened next? Following Labour's landslide, Mr Clarke stood for Conservative leader but was defeated by William Hague and had returned to the backbenches by the time Gordon Brown delivered his first Budget in July 1997.

Labour had already said it would stick to Conservative spending plans for the first two years and it left a number of other measures in Mr Clarke's final Budget untouched.

However, Mr Brown increased tobacco duties by 2p on top of what the Conservatives had done and announced an inflation-linked rise in alcohol duties pending a review of taxation on the industry.

Mr Brown also outlined plans to introduce a 10p "starting rate" of tax on incomes - which took effect in 1999 - and, in the most headline-grabbing move, confirmed the long-trailed £3.5bn windfall tax on the profits of the privatised utilities.

1992: Norman Lamont (11 March)

What was announced: Norman Lamont delivered his second Budget as chancellor on 11 March, less than six weeks before the general election.

Branding it as a "Budget for recovery" after the 1990-1991 recession, Mr Lamont announced a £2bn tax giveaway, halving the sales tax on new cars, cutting betting duty and introducing a new 20% income tax band on the first £2,000 of taxable income.

Labour attacked the package as a "panic-stricken pre-election sweetener" while some economists questioned the lack of action to reduce double-digit interest rates.

What happened afterwards: The Conservatives narrowly won the 1992 election but Mr Lamont's joy was short-lived as the UK crashed out of the Exchange Rate Mechanism and interest rates rose briefly to 15%.

The government's reputation was tarnished by the debacle but Mr Lamont survived to deliver the next Budget in March 1993, where he began a major fiscal consolidation to deal with rising deficit levels.

Mr Lamont' decision to introduce VAT on domestic fuel bills - initially at 8% but rising to 17.5% - was attacked as "shameful" by Labour which said it directly contradicted election promises. He was replaced as chancellor by Ken Clarke two months later and although the economy bounced back the party lost heavily in 1997.

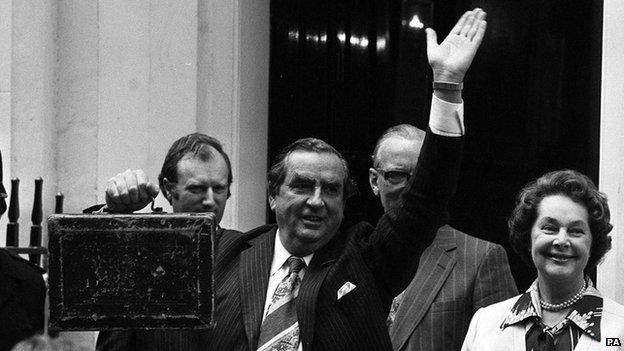

1987: Nigel Lawson (17 March)

What was announced: His Budget speech may have been the shortest for more than 100 years but Nigel Lawson's package - delivered weeks before the general election - was one of the most political of the Thatcher era.

The Budget contained across-the-board tax cuts worth billions.

In what Labour described as a "bribes Budget", Mr Lawson cut the basic rate of income tax by 2% to 27%, froze excise duties, abolished the tax on on-course betting, cut the duty on unleaded petrol and further reduced so-called "death duties".

What happened next? The Conservatives were comfortably re-elected, albeit with a smaller majority than four years earlier.

A year later, Nigel Lawson continued his tax-cutting push, cutting the basic rate of income tax to 25% and increasing personal tax allowances by double the rate of inflation - moves which critics said helped contribute to the inflationary boom which followed.

1979: Denis Healey (April 3)

What was announced: Known as the "caretaker Budget", it came shortly after Labour government lost a vote of confidence in the House of Commons, triggering an election.

Prime Minister Jim Callaghan still had to keep the business of government going and Chancellor Denis Healey's statement was designed to ensure taxes continued to be raised until a new administration was elected.

Mr Healey had limited room for manoeuvre politically and economically, significant net tax cuts having been agreed the year before, and critics said the whole episode was little more a Finance Bill in disguise.

Although child benefit was increased, Labour MPs complained the Budget, which was framed with the co-operation of the Conservatives, was not political enough.

What happened next? After Labour's defeat, the new Conservative government delivered an emergency Budget in June, marking a major change in economic direction.

Chancellor Geoffrey Howe raised VAT from 12.5% - on luxury items - and 8% on most other goods to a single rate of 15%, a move strongly criticised by Labour.

The basic rate of income tax was cut from 33% to 30% and the top rate was reduced from 83% to 60% on "earned income".

1970: Roy Jenkins (April 15)

What was announced: Labour Chancellor Roy Jenkins pledged a "modest stimulus" to an economy that was still recovering from the devaluation of sterling three years earlier.

New tax reliefs worth £220m were announced as was a cut in interest rates to 7%.

But by proceeding, in his words, "fairly cautiously", Jenkins incurred the wrath of some Labour MPs who believed the Budget was not generous enough while the package was labelled in the media as a "non-election" Budget.

What happened next: Labour surprisingly lost the election to the Conservatives. In the 1971 Budget new Chancellor Anthony Barber announced a new value added tax (VAT) would come into force in 1973.

- Published9 March 2015

- Published9 March 2015

- Published17 March 2014