Lib Dem leader resigns: The Nick Clegg Story

- Published

Nick Clegg's political journey has seen him win a bitter Liberal Democrat leadership battle, rise to become deputy prime minister, and face furious criticism over his U-turn on tuition fees.

But despite retaining his own parliamentary seat in 2015, he has resigned as Lib Dem leader after disastrous election results saw the party crushed at the polls.

He was once mentioned in the same breath as Winston Churchill and took his party up to notable highs and now down to painful lows in its popularity.

Personally, he has taken the well-trodden path of failed novelist, American road tripper and schoolboy prankster.

Born in 1967 in Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire, he is the third of four children of Nicholas Peter Clegg CBE, chairman of United Trust Bank.

Nicholas senior is half Russian and his aristocratic grandmother fled St Petersburg after the tsar was ousted.

The younger Nicholas's friends at Westminster School, one of the country's top private schools and located a few hundred metres from the Houses of Parliament, recall the future politician a "spotty" but self-confident teenager with a keen sense of fun.

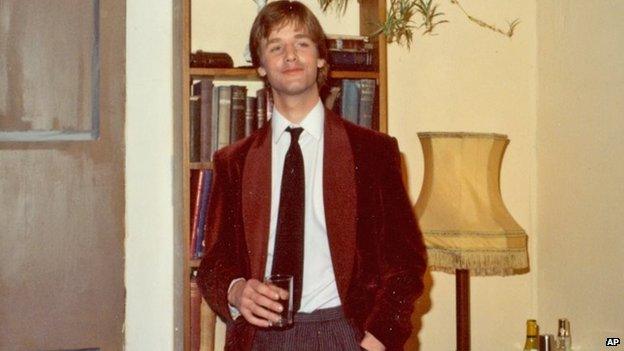

Nick Clegg, second left, on a tennis court with friends in London in 1984

Mr Clegg performed at Westminster School in Noel Coward's comedy Blithe Spirit

He apparently sought out the limelight in school plays, providing a grounding for the grilling he was one day to face when in the political spotlight.

All that energy seems to have spilled over somewhat when, as a 16-year-old exchange student in Munich, he and a friend were arrested for setting fire to a collection of rare cacti belonging to a professor.

Mr Clegg has described the incident as a "drunken prank," of which he was "not proud". He was sentenced to community service and had to spend the summer digging gardens.

After studying anthropology at Cambridge, he briefly became, in his own words, a "ski bum" and tried to write a novel, which he later described as "embarrassingly bad".

He took a road trip across America with his friend Louis Theroux, the documentary maker, and his novelist brother, Marcel.

It was during this time, in the best traditions of road trippers everywhere and to the amusement of the Theroux brothers, he practised transcendental meditation.

After completing a postgraduate scholarship at the University of Minnesota, Mr Clegg began a career in journalism as an intern in New York on left-wing magazine The Nation.

He then had a spell in Hungary, where he was sent as the first winner of the Financial Times David Thomas Prize, before going to work for European Commissioner Leon Brittan in Brussels.

Nick Clegg's leadership battle with Chris Huhne was an uncomfortable one

Nick Clegg, with his wife Miriam, celebrated becoming Lib Dem leader in December 2007

The new Lib Dem leader took over aged 40 from 66-year-old Sir Menzies Campbell

The Tory grandee says the young Mr Clegg always resisted attempts to recruit him to the Conservative Party.

While at the European Commission, Mr Clegg managed aid projects in the poorest parts of Russia and led the EU's negotiations on China and Russia's entry into the World Trade Organisation.

Little wonder that, after all his travels, he should be able to speak French, Dutch, German, and Spanish.

A brief spell as a lecturer at Sheffield University followed before he became a Liberal Democrat MEP in 1999.

In 2000, Mr Clegg married leading commercial lawyer Miriam Gonzalez Durantez,, external a former Middle East expert at the Foreign Office. The couple, who met while studying at the College of Europe in Bruges, live in south-west London with their three children, Antonio, Alberto and Miguel.

She has revealed that she and their three boys have been writing an anonymous cookery blog, external for three years.

In it, the family share recipes including shrimp tortillas, milk buns and lemon posset, apparently without Lib Dem advisers knowing. What they think of the Cleggs' cooking is also unclear.

Nick Clegg: "I must take responsibility and therefore I announce that I will be resigning as leader of the Liberal Democrats''

Eventually the young MEP was talent-spotted by the then-Lib Dem leader Paddy Ashdown and it was not long before he was swapping Brussels for Westminster.

Despite his relative inexperience, he was tipped as a future leader almost from the moment he arrived in the Commons in 2005, as the MP for Sheffield Hallam.

He did not have to wait long to get his chance, when Sir Menzies Campbell unexpectedly quit as leader in 2007.

Mr Clegg was part of a new generation of Lib Dem MPs who saw themselves as classical liberals - believers in free trade, free markets and individual liberty.

But despite starting as firm favourite, he was nearly beaten to the leadership by a figure from the left of the party, Chris Huhne, after a closely fought, and at times fractious, contest.

Mr Huhne had to issue an apology , externalover a briefing paper printed during the leadership battle which described his leadership rival as a "calamity".

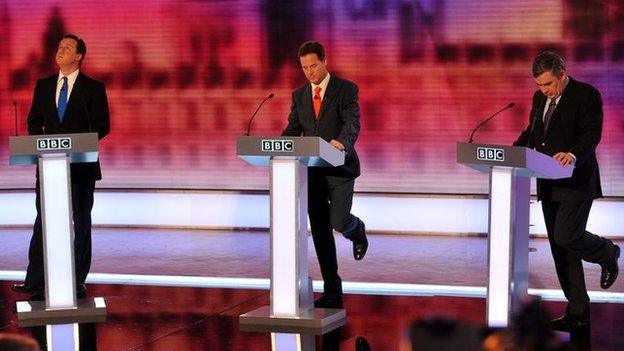

Mr Clegg was widely acknowledged to have come out best of three party leaders in the first TV debate in 2010

David Cameron and Nick Clegg formed a coalition government in 2010

The defining moment of Mr Clegg's political career came in the May 2010 general election campaign, when he took part in Britain's first televised leaders debates.

The Lib Dem leader outshone David Cameron and Gordon Brown in the first of their three encounters, with "I agree with Nick", external becoming the catchphrase of the debate, falling from the lips of his opponents on several occasions.

Mr Clegg's performance sparked headlines claiming he was the most popular politician since Winston Churchill and vitriolic attacks from right-leaning newspapers who had previously ignored him.

The expected poll boost largely failed to materialise, but the Lib Dems still had enough MPs to effectively hold the balance of power in a hung Parliament when the votes had been counted.

Mr Clegg, as the new deputy prime minister, famously stood next to the new prime minister, David Cameron, in the garden at 10 Downing Street for the new government's first press conference.

In a light-hearted moment, Mr Cameron admitted he once branded his new coalition partner a "joke". At which point the deputy PM then pretended to storm off - prompting Mr Cameron to plead with him to "come back".

His unfavourable assessment of the man who was now his closest new government colleague was recorded in a 2008 book by GQ editor Dylan Jones, who asked him for his favourite joke.

"Nick Clegg, at the moment," Mr Cameron had apparently told him.

When asked by a reporter about the jibe and whether he said it, Mr Cameron turned to Mr Clegg and confessed: "I'm afraid I did."

Nick Clegg fought his second general election campaign as Lib Dem leader in 2015

Mr Clegg's campaigning has taken him to such locations as this nursery in Bearsden, Scotland

This verbal battering did not seem to get the pair off on the wrong foot, however.

When making his deal with the Conservatives, Mr Clegg reasoned that he could secure more of the Lib Dems' priorities in coalition with Mr Cameron than with Labour - and he won the backing of his party for the deal at a special conference.

He pointed to his early successes where he won a "pupil premium" to pump money into schools in disadvantaged areas, a referendum on electoral reform - which he lost - and an increase in the tax-free allowance to £10,000.

In return, he accepted the scale and speed of the Conservatives' spending cuts, sparking a mass defection of left-wing Lib Dem members and voters.

He also decided to support a rise in tuition fees, something he had opposed when in opposition.

In fact, he, along with all Lib Dem MPs elected in 2010, had signed a National Union of Students (NUS) pledge to vote against any rise.

It was a move that split his MPs, led to much agonising among his ministers and a cry of betrayal from students who had voted for him - and who now took to the streets in protest.

The Lib Dem leader said last year, external that he had "perhaps rightly" received a lot of criticism over the tuition fees U-turn. His apology even went viral after being set to music., external

The Liberal Democrat leader remains an influential figure in British politics

That, and other compromises of coalition are being seen as the major reason for the Liberal Democrats' disastrous general election performance, with the party forecast to retain just eight of their 57 House of Commons seats.

Mr Clegg retained his Sheffield Hallam seat, but in a speech resigning as Lib Dem leader, he said results had been "immeasurably more crushing and unkind than I could ever have feared", adding that he "of course... must take responsibility".

His role in government is now over, but what influence he will be able to bring to bear on the unpredictable British political landscape remains to be seen.

Nick Clegg: "I must take responsibility and therefore I announce that I will be resigning as leader of the Liberal Democrats''