Tory MPs keep powder dry on Europe for now

- Published

David Cameron is set for talks over reform of the UK relationship with the European Union

The UK's future direction for at least a generation, external hangs precariously on an uncertainty, balanced on the tip of the unknown.

I am talking of course about the planned referendum, external on the EU.

The brilliant thing about referendums, and one of the features that makes them so irksome for politicians is their binary clarity - "Yes" or "No", "In" or "Out".

This one will be like that, but it isn't at the moment.

For now, the most important group of potential voters are the "Maybes".

They are not unsure because they are hesitant Harrys and Harriets who haven't grasped the big issues.

It is much more political than that. Some big names are rallying around the banner of "Maybe".

The Foreign Secretary Phillip Hammond is one of them, external, and perhaps the most important is the mop-headed mayhap Boris Johnson, external.

Their eventual decision depends, they say, on what change in the relationship David Cameron manages to negotiate - and that may well depend on what they and others argue, in political cabinet, he should demand.

Boris Johnson wants major reform to come out of negotiations

This is unknown because it is as yet undecided.

Indeed, I am fairly sure almost all Conservative MPs will be herded into the "Maybe" camp by a twitch of deferent loyalty on one flank, the cracking whip of strategic cunning on the other.

Playing the part

Those who know with certainty in their own hearts they will vote "No" may feel they have to give the prime minister a chance, or appear grossly disloyal.

This has the added advantage that having played the part of a loyalist waiting with open-jawed admiration for the prime minister to return home with a piece of paper, their eventual disappointment will pack more heft.

At the end of the process, they can declare that, despite all their high expectations, the deal is not good enough, and the obdurate EU has left them with no choice but to campaign for an "Out".

Equally, those who are determined to stay in might as well drape themselves in temporary Euroscepticism and mutter about how hard it is for Mr Cameron to "squeeze anything out of that lot".

When Mr Cameron returns with a deal, however paltry, they can proclaim it a master stroke that forces them into the "Yes" camp.

Still, some will have a genuine bottom line.

It is not clear if the prime minister himself is one of them.

He has set out, in rather loose terms, his aims, in the Sunday Telegraph, external last March.

The trouble with most of them is that success would be difficult to measure.

Conservative manifesto on Europe:

We will legislate in the first session of the next Parliament for an in-out referendum to be held on Britain's membership of the EU before the end of 2017.

We will negotiate a new settlement for Britain in the EU. And then we will ask the British people whether they want to stay in on this basis, or leave.

We will protect our economy from any further integration of the Eurozone.

The integration of the Eurozone has raised acute questions for non-Eurozone countries like the UK. We benefit from the single market and do not want to stand in the way of the Eurozone resolving its difficulties.

But we will not let the integration of the Eurozone jeopardise the integrity of the single market or in any way disadvantage the UK.

We want to see powers flowing away from Brussels, not to it. We want national parliaments to be able to work together to block unwanted European legislation.

And we want an end to our commitment to an "ever closer union", as enshrined in the treaty to which every EU country has to sign up.

What sort of change would ensure "businesses liberated from red tape" or "powers flowing away from Brussels"?

Words alone would not suffice for those who think such changes are vital, external if the UK is to stay in the EU - after all, the European Commission would say it backs both.

"Free movement to take up work, not free benefits" is more concrete and eminently achievable but may not look like the "fundamental" change in relationship that is promised.

Angela Merkel has ruled out any attempt to limit free movement of people

But "new mechanisms in place to prevent vast migrations across the Continent" looks much easier to declare as a "win" or "lose".

After persistent warnings, particularly from German Chancellor Angela Merkel, that "free movement of people" was not up for grabs, the prime minister appeared to drop the idea.

But he told the House of Commons only two months ago: "In the coming two years, we have the opportunity to reform the EU and fundamentally change Britain's relationship with it.

"We have the opportunity to build a European Union that is more competitive, more flexible and more accountable to the people, where powers flow back to member states, not just away from them, and where freedom of movement is no longer an unqualified right."

How much would the EU have to qualify that right, to persuade the doubters?

Would a promise to stop putative Serbians coming to Britain after their country joins, in perhaps 2030, do the trick?

Again, that is unknown and uncertain.

At the moment, most backbenchers are keeping their heads down and powder dry.

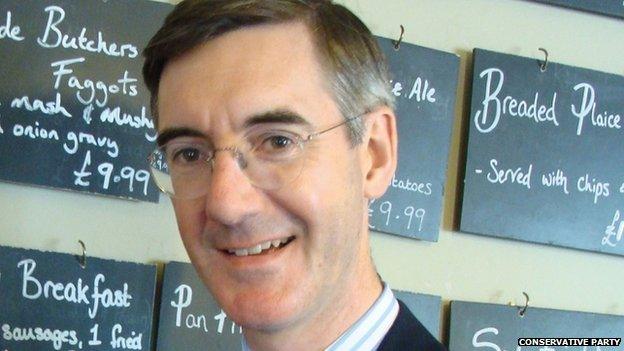

Jacob Rees Mogg says free movement of people is a key issue

But Jacob Rees Mogg, MP for North East Somerset and member of the European Scrutiny Committee in the last Parliament, told me: "I think the touchstone for renegotiation will be the free movement of people.

"It is one of the four freedoms of the European Union, and if the EU is willing to give ground on that it will show that it is willing to consider a fundamental reform rather than just tinkering at the edges.

"So it is symbolically important as well as representing a deep concern of the British people."

This is admirable in its clarity, and I suspect it will be a touchstone too for many of his colleagues.

Others may set the bar higher or lower, but one new MP told me: "I wouldn't like to be in the prime minister's shoes.

"He knows it has to be real - he can't just come back with a bit of polish on it."

The prime minister's challenge is to come back with a deal so bright and sunny that the snows of uncertainty melt away to reveal the sunny uplands of victory. Is that likely? Maybe.