Lady Thatcher's Falklands memoir tells of her 'anguish'

- Published

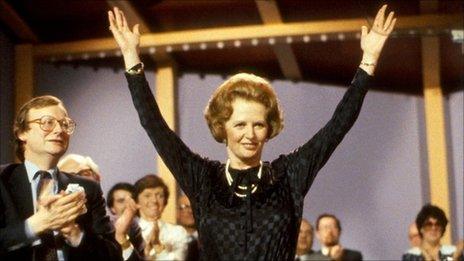

The retaking of the Falklands was a defining moment in Margaret Thatcher's premiership

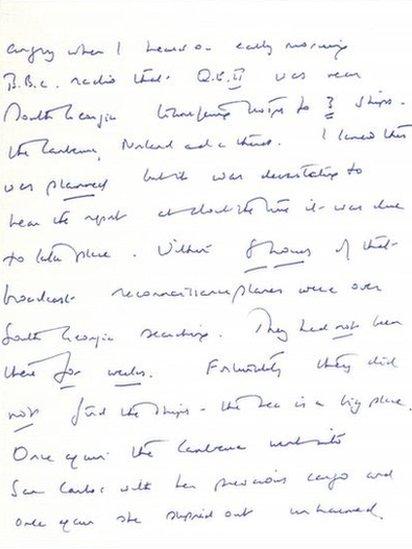

A private memoir of the Falklands War written by Margaret Thatcher, detailing disagreements with ministers and her "guilt" over British casualties, has been published for the first time.

In the 17,000 word document, external, written a year after the war, she laments the loss of "our bravest and best".

The document also highlights concerns about media coverage of the conflict.

It is among a selection of private papers given to the nation by the ex-PM's estate in lieu of inheritance tax.

Other material released include her personal account of the Fontainebleau Summit of European leaders in 1984, when she secured the UK's budget rebate, the final draft of her remarks when she entered Downing Street for the first time in 1979 and the text of her "lady's not for turning speech" at the 1980 Conservative Party conference.

Lady Thatcher made a number of additions to the text after 1992

The donation of the papers to the Churchill Archives Centre, external, which already holds the bulk of the former Conservative leader's personal and political files, has settled an inheritance tax bill in excess of £1m that was owed by her estate.

'Miracle'

Lady Thatcher, who died in 2013, was Britain's long-serving post-war prime minister, serving between 1979 and 1990.

The 1982 Falklands conflict, in which a British taskforce recaptured a group of British overseas territories in the South Atlantic after their invasion by Argentine troops, was a defining moment in Margaret Thatcher's premiership.

The 128-page memoir, written at Chequers over the 1983 Easter holiday, is a candid and, at times, highly personal account of the political and diplomatic manoeuvrings in the run-up to the conflict and the conduct of the military campaign itself.

The account of the war, which she described as a "miracle wrought by ordinary men and women with extraordinary qualities", reveals:

She was "at loggerheads" with her foreign secretary Francis Pym for much of the period, disagreements which came to a head over whether to accept a US-brokered agreement to try and avert military action

She accused the BBC and ITV of "assisting the enemy" by discussing possible military developments before they happened

Chancellor Geoffrey Howe was excluded from the committee set up to prosecute the war on the advice of former Conservative prime minister Harold Macmillan

Ministers and commanders discussed the threat posed by the Argentine warship, the Belgrano, shortly before it was sunk

Stocks of napalm bombs were discovered after UK troops took Argentine positions at Goose Green

Margaret Thatcher insisted the Pope did not cancel a planned visit to the UK during the conflict but said it would be wrong for him to meet her or any other ministers

The prime minister rejected US attempts to "mediate" between the two sides in the run-up to the conflict but praised the Reagan administration's "magnificent" support for the UK's position

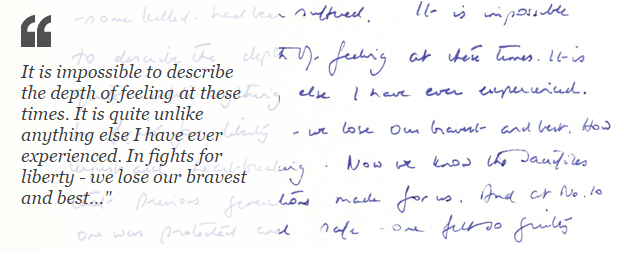

Among the most striking passages in the memoir are the former prime minister's reactions to military successes and setbacks during the hostilities, which cost the lives of 255 British servicemen and 655 Argentineans.

Reacting to the attack on HMS Glamorgan, 14 of whose personnel were killed when it was struck by an Exocet missile, she wrote:

"It is impossible to describe the depth of feeling at these times. It is quite unlike anything else I have ever experienced."

It is impossible to describe the depth of feeling at these times. It is quite unlike anything else I have ever experienced. In fights for liberty - we lose our bravest and best..."

"In fights for liberty - we lose our bravest and best. How unjust and heart-breaking. Now we know the sacrifices that previous generations made for us. And at No 10 one was protected and safe - one felt so guilty at the comfort."

Reflecting on the "bitter battle" for Darwin and Goose Green, the most fiercely fought infantry engagement of the war, she praises the personal sacrifice of Lieutenant Colonel Herbert 'H' Jones, who was awarded a Victoria Cross posthumously after leading the attack on Argentine positions.

"At one point it seemed impossible to break through. At that time 'H' made his famous courageous advance. His (Victoria Cross) life was lost but his bravery was the turning point in the battle."

'Total retreat'

While recognising the contribution made by other ministers, including the "splendid" defence secretary John Nott and deputy prime minister Willie Whitelaw, the prime minister lays bare the differences between her and Mr Pym, who became foreign secretary after his predecessor Lord Carrington's post-invasion resignation.

Margaret Thatcher disagreed with her foreign secretary over the desirability of a political solution

Despite her disagreements with the BBC, Mrs Thatcher praised the reporting of the late Brian Hanrahan

She notes that she had to overcome his "objections" on a number of occasions, over the establishment of an maritime exclusion zone around the islands and over her belief that any diplomatic solution that rewarded aggression and did not respect the wishes of the islanders for self-determination should be rejected out of hand.

Their differences came to a head after Mr Pym recommended the UK sign up to a US-brokered agreement to avert war which she described as "complete sell-out" and which would lead to a "complete takeover" of the islands by the Argentines.

Mr Pym, she suggested, agreed with the US government which was "sceptical about our capacity to achieve a satisfactory military solution and thought international support would evaporate quickly after the first shot had been fired".

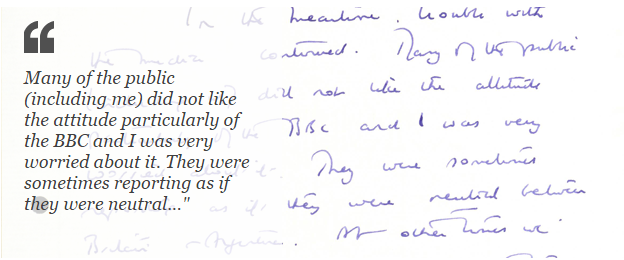

Many of the public (including me) did not like the attitude particularly of the BBC and I was very worried about it. They were sometimes reporting as if they were neutral..."

Mrs Thatcher suggested she would have had to have resign if the war committee sided with Mr Pym rather than her.

"I repeated to Francis that we could not accept them. They were a total retreat from our fundamental position. He said he thought we should accept them. We were at loggerheads.

"A former defence secretary and present foreign secretary of Britain recommending peace at that price," she added. "Had it gone through the (war) committee I could not have stayed."

'Assisting the enemy'

In the memoir, Lady Thatcher elaborates on her "trouble" with the reporting of the war by the British media, particularly the well-documented battles between the government and broadcasters over the content and tone of their coverage.

"Many of the public, including me, did not like the attitude particularly of the BBC and I was very worried about it. They were sometimes reporting as if they were neutral between Britain and Argentina.

"At other times we felt strongly that they were assisting the enemy by open discussions with experts on the next likely steps in the campaign. This applied to ITV as much as to BBC.

"This of course was the first conflict we had fought without censorship. The media and the government took totally different views. My concern was always the safety of our forces. Theirs was news."

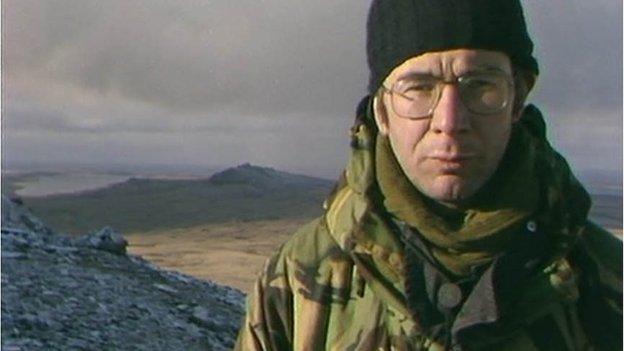

However, she complimented the work of one of the BBC's most senior correspondents, Brian Hanrahan, whose description of a sortie by Royal Navy harrier jets from HMS Hermes was among the most famous of the war.

"The Argentineans were in a position to send photographs to the outside world - we weren't," she wrote.

"They claimed many of our planes were shot down but Brian Hanrahan in a famous broadcast put the record straight when he said 'I counted them all out, and I counted them all back'. What a relief - there was some damage but not a lot."

- Published8 April 2013

- Published8 April 2013