7/7 anniversary: Is the UK any safer now?

- Published

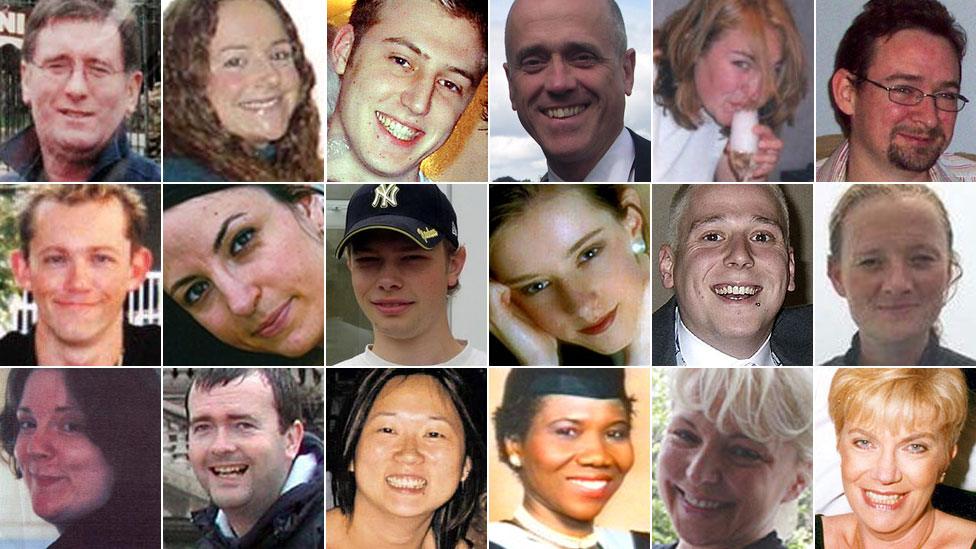

It is 10 years since 52 people died and hundreds were injured in London in a series of attacks on the capital's tube and bus network. A decade on, are we any safer than we were then?

The short answer? Yes and no.

Since the London bombings there have been enormous improvements in the way the police, the security service, community leaders and the public all tackle the threat from international terrorism.

The authorities believe that it would be far harder, in 2015, for terrorists to carry out a complex, co-ordinated bomb plot like 7/7 without being detected. But conversely, that threat has diversified into something far harder to detect and stop.

Listed below then is a simplified balance sheet, as it were, of the ways we in Britain are safer, or not, from a terrorist attack.

Improved detection

Ministers have said the security services have foiled numerous planned attacks since 2005

MI5, whose job it is to detect terrorist plots using covert intelligence, has roughly doubled in size to about 4,000 people over the past decade. These now come from a wide range of backgrounds, languages, religions and ethnicities, more representative of the urban populations from where threats tend to emanate.

Old rivalries with the Metropolitan Police have largely been set aside. The two organisations work in tandem and have set up a number of regional counter-terrorism units (CTUs) all over the country to give them a national picture of the threat.

MI5 also works more closely with the Secret Intelligence Service and GCHQ to use both human intelligence, for instance overseas-based spies, and intercepted communications to get ahead of plots at the earliest stages.

Conversely, this has led to accusations from some quarters of excessive surveillance, harassment and the erosion of civil liberties. Some security experts are highly critical of the government's approach.

"Despite the erosion of civil liberties, invasive security checks and greater state access to our personal information, we are seemingly further from defeating terrorism than ever," says Prof Lee Marsden, from the University of East Anglia.

Raffaello Pantucci, an expert on jihadism and author of the book, We Love Death as You Love Life, takes a different view of the track record of MI5 and the police in the light of 7/7 and the Woolwich murder of Fusilier Lee Rigby in 2013.

"We have had two successful attacks in 15 years which is a pretty good standard to be operating by, a pretty good success rate," he says.

"On the other hand I think they are dealing with a very dynamic, evolving threat picture, that in some cases the security services have been slow to pick up on."

Read more - 7 July attacks

The Syria factor

Islamic State extremists are believed to be encouraging British jihadists to commit attacks on their return

Almost the entire UK government apparatus underestimated both the appeal and the threat now emanating from the Syria-based terror group that calls itself Islamic State (IS).

Latest estimates put the number of foreign fighters flocking to join the group, or live under its control, in excess of 20,000. That is more than the number who went to Afghanistan to train in al-Qaeda camps when the Taliban were in charge for five years.

Official estimates put the number of Britons who have gone to Syria to join IS at 700, with around half that number returning to the UK. Real figures are probably higher.

Not all those who return need to be watched. Some come back disillusioned, some come back traumatised and need counselling.

But counter-terrorism officials believe there are concerted efforts by IS leaders in Syria to persuade Britons to carry out attacks in the UK, in some cases urging followers who have not even travelled to the Middle East.

The sheer numbers getting drawn to IS, for a whole range of reasons, means that the 'Syria factor' places an enormous workload on those trying to head off the next plot.

"Since 7/7 lots of different places have started to emerge as a source of a potential threat," says Aimen Deen, a former member of al-Qaeda who now works for a Middle East-based consultancy.

"Be this in Yemen, be this in North Africa, be this in Somalia or more recently in Syria and Iraq, where we can see that there are different groups and networks that are trying to launch attacks."

Multiplication of ways of attack

So-called "lone wolf" attacks such as that seen in Tunisia are among those most feared by the authorities

Al-Qaeda's primary modus operandi was big, co-ordinated, centrally planned attacks using synchronised suicide bombings. 9/11, 7/7, the Madrid and Bali bombings were all examples of this.

So too would have been the 2006 liquid bomb airline plot, if it had not been intercepted in time. That threat has not gone away.

There are still jihadist planners in Yemen, Syria and Pakistan who would like to execute just such a big, signature attack on a list of Western countries, of which Britain, the US, France and Denmark are at the top.

One of the most serious threats the UK has been rehearsing for, ever since the Mumbai siege of 2008, is a "marauding attack" by heavily-armed gunmen targeting defenceless citizens in a crowded city centre.

Powerful, automatic weapons are much harder to obtain in Britain than they are on the continent but that may not always be the case.

Most of today's would-be jihadist attackers are interested in a much simpler, cruder approach, one with minimal communications that can be intercepted, with as small as possible a circle of people in the know.

MI5 are believed to have between 2,000-3,000 people "on their radar", meaning people who are known to have extremist views or be in contact with extremists, but who have not necessarily committed a criminal offence.

Trying to second guess when someone's extremist views are going to translate into action, like the killers of Lee Rigby in Woolwich, is an ongoing challenge for the police and spooks.

They point out that "being on the radar" is not the same as "being under the microscope" and that to watch all those people all the time would require a network of informants akin to the Stasi in the former East Germany.

"Plots are harder to detect right now because they moved from being centralised plots, organised by cells overseas into plots that are basically carried out by lone wolves, who are recruited in isolation and who are not in touch with other cells," says Aimen Deen.

"Therefore when they decide to take action it is difficult to detect them in advance so it became harder and harder for security agencies."

Encryption

Deciphering encrypted messages can be a laborious process

Back in 2005 international terrorists communicated mainly by email or mobile phone.

Today the choice of methods at their disposal has ballooned, from easily encrypted messages to those hidden in online games. GCHQ has enormous and controversial powers to tap into communications but its operatives have to know what they are looking for.

Often, says one expert, it is not so much a case of looking for a needle in a haystack as looking for a certain type of needle in a haystack made up of needles.

Decrypting terrorist communications, once they are zeroed in on, is labour intensive as they can pass through dozens of stages of encryption using multiple nodes around the world.

Sometimes it can prove a false alert and sometimes the trail can reach a dead end, as plotters switch seamlessly to a different means of communication.

Threat level

Britain is currently at a national terror threat state of "severe", the second highest in a ranking of five.

Officially this means a terrorist attack of some sort is thought "highly likely", ranging from a single jihadist with a machete on the High Street to a 7/7-style attack.

This assessment is based on the intelligence being fed into a unit called JTAC, the Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre, but it is far from complete.

MI5 and the police have stopped a very large number of plots since the 7/7 bombings but they also missed the 21/7 plot two weeks later - it failed because the bombs did not work - and the Woolwich attack of 2013.

Although today Britain has an almost negligible military presence in Iraq and Afghanistan (one of the main reasons given by jihadists for their targeting a decade ago), the threat has still multiplied and morphed.

How long will it last?

"Well it started a generation ago," says former jihadist Aimen Deen. "There is no reason to believe that it won't last another generation or possibly even two".

- Published3 July 2015