Would UK military action against IS in Syria be legal?

- Published

One of the big questions facing MPs after the summer recess could be whether to authorise military intervention against so-called Islamic State (IS) extremists in Syria.

Labour leadership contender Andy Burnham says he is "struggling, external" with whether UK action would be legal or not. So what are the key legal questions?

Commons vote

Parliament has already rejected military intervention in Syria, in 2013. Ministers say circumstances have changed since then (notably with the rise of IS) and that they would only proceed this time with the backing of Parliament. But this is not technically necessary. Although it has become convention since the 2003 Iraq war, there is no legal requirement, external for Parliamentary approval for military action.

The government's view

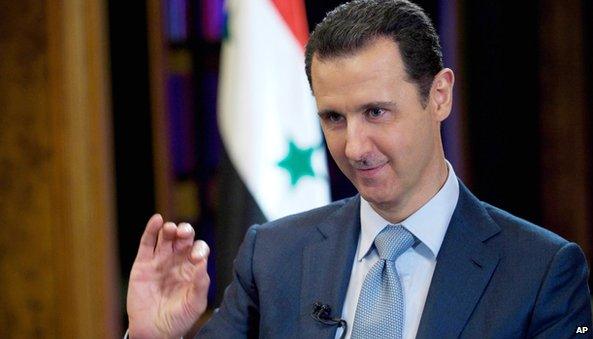

Ministers say they would not proceed without a Commons vote - but they believe they have the authority, under international law, to intervene. Last month, Defence Secretary Michael Fallon said there was "no legal bar" to the UK operating in Syria. In September, David Cameron suggested the UK could legally take military action in Syria without a request from President Assad, saying the Syrian president is "illegitimate".

Iraq comparison

The Iraqi government requested assistance in the fight against Islamic State

The UK is already carrying out air strikes on IS targets in Iraq. The UK says that, external as the Iraqi government requested intervention, this provides a "clear and unequivocal legal basis" for the military action. But no such request has been received from the Syrian government, and the UK sees the regime as illegitimate in any case. This means the legal arguments around intervention in Syria would be shaped by the complexities and conflicting interpretations of international law.

The United Nations

A United Nations resolution is seen a remote prospect

The UN Charter, external bans "the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state" unless used in self-defence or authorised by a UN resolution. Those are the two "classic justifications" for military action, Prof Philippe Sands QC of University College London told the BBC.

A UN resolution is unlikely given Russian opposition, leaving the option of self-defence. This would require ministers to show military action was needed to prevent attacks on the UK or its citizens emanating from Syria. Alternatively, the self-defence argument could be used in relation to Iraq, which has already requested military assistance. This is the argument used by the United States, which is carrying out air strikes in Syria.

As to whether this would work, "we simply do not know enough about the facts" to say definitely whether the self-defence argument is justified, says Prof Sands. He believes it would be "a bit of a stretch" on the basis of what is publicly available, adding that the UK appears to have "no strategy and no clear basis of information to explain to the public what it is doing, and why it believes it is entitled in law to use force by way of self-defence".

Humanitarian grounds

In 2013 the UK government argued in favour of intervention against President Assad's government on humanitarian grounds

Another option would be to justify the action on humanitarian grounds. This was the basis of the government's case for intervention in 2013, when it focused on the possible use of chemical weapons by Syrian President Assad. Its legal position, external, published in August 2013, set out the three conditions that had to be met:

There had to be convincing evidence of "extreme humanitarian distress on a large scale, requiring immediate and urgent relief".

There must be no "practicable alternative" to the use of force

The proposed use of force must be "necessary and proportionate" and "strictly limited in time and scope to this aim"

"This puts the evidential bar both high and wide," BBC legal correspondent Clive Coleman wrote at the time.

The question would be whether the changed circumstances, with IS - also known as ISIS - militants controlling parts of Syria and fighting against government forces, would meet the test.

Dr Jonathan Eyal, international director at the Royal United Services Institute, told the BBC there would be a "quite plausible case".

"Given the behaviour we know of ISIS, the circumstances of the horrific civil war in Syria, it's not difficult to construct a case that the humanitarian danger is grave and is immediate," he says.

Other options

As well as the UN rules, "customary international law" has been established over the years.

One option would be the right of "hot pursuit" of IS across borders, Dr Eyal says. Given that Iraq has requested international assistance in the fight against IS militants, the UK could argue that unless it can pursue them into Syria, they could "seek refuge across the border and the situation will never end", he says.

This argument is strengthened by the inability of the Syria government to control its own territory he says, adding that hot pursuit is "not an argument that lawyers are very comfortable with, but it has been made before".

Will everyone agree?

Defence Secretary Michael Fallon holding talks with Iraqi officials

No. Both the hot pursuit and humanitarian intervention arguments are "controversial and contested", Dr Eyal says, with governments accused of "abusing the system".

Some legal experts are not convinced any air strikes without specific Security Council authorisation would be consistent with international law, a Commons briefing paper, external points out.

Isn't the UK already involved in Syria?

Sort of. A US-led coalition is already carrying out air strikes in Syria. Last month it emerged UK pilots had been embedded with coalition forces and conducting air strikes over Syria against IS. Amid criticism from Labour, Mr Fallon said embedding forces was "standard practice" and their engagement was not a "British military operation".

Will politics play a part?

Very much so. The government's insistence on securing Parliamentary approval means it will be MPs' interpretations of these intricacies of international law that will be key.

Labour leadership contender Jeremy Corbyn is opposed to any military intervention

Last time MPs debated military intervention in Syria, opposition from backbench Conservatives and Ed Miliband-led Labour was enough to defeat the government.

However, MPs have since overwhelmingly backed action in Iraq, where the target was IS militants. Since those votes, the make-up of the Commons has changed, with the Conservatives holding a majority.

The identity of Labour's next leader - with surprise frontrunner Jeremy Corbyn certain to oppose any air strikes - is another complicating factor.

- Published10 August 2015

- Published20 July 2015

- Published30 August 2013