The old question at the heart of Labour's current conflict

- Published

When Jeremy Corbyn takes to the conference stage in Brighton this weekend, he will be greeted with delighted acclamation by the Labour Party's left wing, jubilant at the election of one of their own to lead the party towards the sunlit uplands.

Yet while the conference centre rings with applause, the air will also be heavy with the memory of the last time the left was in the ascendancy and fears it is, instead, the wilderness that once again awaits.

That this year's Labour Party conference will be one of the most interesting for a generation is not in doubt, but what is uncertain is the extent to which the team assembled under Mr Corbyn's new leadership will be able to present the party as a credible alternative government.

That of course was also the problem 35 years ago as the party, in pursuit of undiluted socialist purity, engaged in internal disputes of such acrimony that it dissipated into political oblivion for a couple of decades.

Blair's shake-up

It was the choice of Tony Blair as party leader and his subsequent triumphant election in 1997 that brought an end to that long, unhappy period for the party.

The irony is that in shaking up the "old" Labour Party and its organisation, Mr Blair and his "new" Labour acolytes so alienated the party's traditional supporters that they deserted in droves.

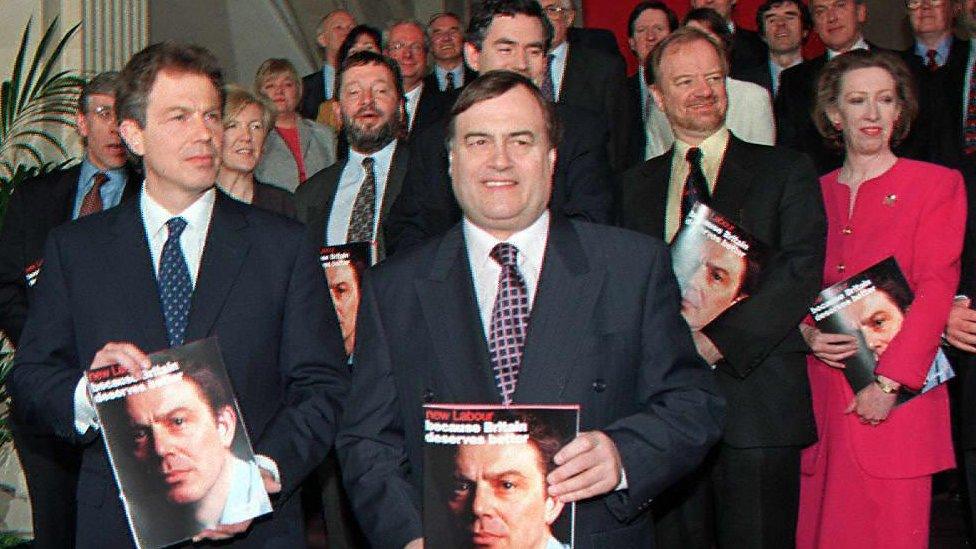

Tony Blair, John Prescott and Labour MPs hold the party's "New Labour" manifesto in 1997

Only now have they been inspired once more by Mr Corbyn's vision of the political road to a decent caring society, an ideal that has attracted also an army of youthful optimists with no previous political convictions.

And it is an army:

more than a quarter of a million people voted for Mr Corbyn

50,000 new members have joined the party since his election

the Labour Party is now almost equivalent in size to that of 400,000 members led by Blair in the glory days of 1997

There were even more members in the 1970s, but the figures were distorted into millions by the closer links with the then all-powerful trade unions.

It was their members and votes that also played an important part in the rows and ructions that marked the years under the leadership of Michael Foot in the early 80s.

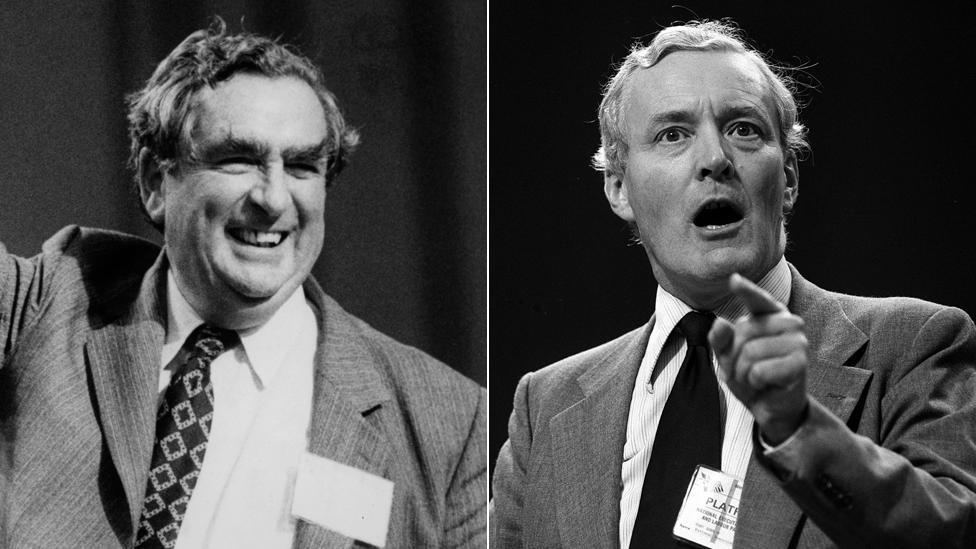

Michael Foot's leadership was marked by trade union rows

The conflict between left and right in 2015 will be very different from that which raged within the party from 1979 onwards, but in essence it will nevertheless boil down to a debate next week, as it did all those years ago, about the same significant question.

And that is whether some things are more important than winning elections.

Constitution questions

It seems extraordinary in retrospect, but the root of Labour's historical difficulties in the 1980s lay in attempts to reform its constitution.

There were disagreements and contested votes and crises at successive conferences about such iconic political issues as Britain's independent nuclear deterrent and the future of the UK's role in a developing European community.

The Gang of Four - William Rodgers, Shirley Williams, Roy Jenkins and David Owen - split from Labour in 1981 to form the Social Democratic Party

The swell of anti-European sentiment even produced the most acrimonious special conference at Wembley when the impassioned European enthusiasts led by David Owen (Roy Jenkins was then absent abroad, still at the European Commission) fought their last failed battle before leaving to form the breakaway Social Democratic Party.

And I recall watching a jubilant Neil Kinnock in Blackpool's Winter Gardens cheering the 1982 Labour conference decision in favour of unilateral nuclear disarmament, a decision which many argued would help lose the party the general election the following year.

But the basis of the real row was a campaign to democratise the party's internal structure, spearheaded by the late Tony Benn - whose latter-day political sainthood was much resented by many in the Labour Party who held him personally responsible for its subsequent 18 years out of office.

The issues were mandatory reselection of all MPs, thus holding them to account by party members, an electoral college of unions and party members as well as of MPs to elect the leadership and democratic control of the election manifesto.

Healey v Benn

Denis Healey (left) narrowly defeated Tony Benn in the Labour deputy leadership contest in 1981

It was these issues that caused the bitter dissension in the party, not only between left and right, but within the left between hardliners and moderates.

That latter fight was led by Mr Kinnock and culminated in the extraordinary battle for the quite unimportant role of deputy party leader between Denis Healey and Tony Benn.

Mr Healey won what was actually the battle for the party soul by 50.4% to 49.5% of the newly formed voting college.

He only did so because Mr Kinnock withdrew his own support from Mr Benn's campaign by abstaining from the vote.

Mr Kinnock was publicly jeered.

I was there in Brighton when Dame (as she is now) Margaret Beckett asked him why, as a "Judas", he did not contribute "30 pieces of silver" to the collection at a Tribune rally.

Despite Mr Benn's defeat, those "reforms" were all duly enacted for a while, but were they more important than winning elections?

The Labour Party didn't think so by the time Tony Blair took it in hand and won three in a row.

The reforms had been largely forgotten by 1997 when Mr Blair's landslide ensured that all such left-wing fancies went down the equivalent of Orwell's "memory hole".

Ironically, it was the change of those controversial rules for the leadership election - that went through unnoticed under Ed Miliband - which then allowed the £3 registered supporters to help vote Mr Corbyn into the post.

And now? Is power more important than principle? Well, that is what we might find out next week.

Julia Langdon is a political journalist, broadcaster and author. She is the former political editor of the Sunday Telegraph and Daily Mirror.

- Published25 September 2015

- Published24 September 2015

- Published24 September 2015

- Published14 September 2015

- Published12 September 2015

- Published12 September 2015

- Published24 September 2016