Deficit, the budget charter and Labour's U-turn explained

- Published

Jeremy Corbyn appointed John McDonnell as his shadow chancellor

Labour's decision to change its policy on George Osborne's plan to try to make it legally binding on future government's to balance their books each year, has brought to the surface some of tensions within the party following Jeremy Corbyn's journey from rank outsider to party leader.

Few MPs had backed the member for Islington North, and many were unhappy that he chose his ally from the Labour left, John McDonnell, as shadow chancellor.

When Mr McDonnell explained his decision to reverse his support for Mr Osborne plan - which are set out in an updated Charter for Budget Responsibility - to labour MPs, shouts of criticism were audible outside the room, and one ex-minister described the process as a "shambles".

What the charter says

The charter commits the government to keep debt falling as a share of GDP each year and achieve a budget surplus by 2019-20. Governments will then be required to ensure there is a surplus in "normal times".

This will be when the independent Office for Budget Responsibility judges that the UK is experiencing real GDP growth of less than 1% a year, as measured on a rolling four-quarter basis.

Key terms explained

If there's a budget surplus: The government is raising more in tax than it is spending

If there's a deficit: The government is spending more than it is receiving

National debt: The amount of money owed by the UK government, built up over many years

Fiscal: A word that basically means "the government's finances"

Osborne's objective

Chancellor George Osborne's plan has been seen as a potential trap for Labour and a test of its willingness to commit to spending cuts. His number two at the Treasury, David Gauke, however, insists that is not a political stunt.

He told the BBC it would improve accountability and help ensure a "sound framework for delivering sound public finances" with any chancellor having to suffer the "political embarrassment" if they did not meet its requirements.

The U-turn

There were anti austerity protests outside the Conservative Party conference in Manchester

Soon after his appointment, Mr McDonnell said he would support, external the charter, saying Labour was serious about deficit reduction - although he had a markedly different approach to the Conservatives towards balancing the books (he says Labour would spend more and grow the economy and collect more taxes from companies to balance the books rather than balancing the books by cutting spending).

But he has now pointed to a "growing reaction" to the "nature and scale" of public spending cuts, saying Labour will vote against the charter to "underline our position as an anti-austerity party". Labour will set out an alternative plan for tackling the deficit, he says.

The reaction

Many Labour MPs agree the charter should be opposed, but are unhappy at the way the decision has been reached.

Mr McDonnell's predecessor as shadow chancellor, Chris Leslie, says the decision to "go from one extreme to the other... sends the wrong message to the general public".

Mr Corbyn's supporters say the Parliamentary Labour Party should accept the mandate of his comprehensive victory in the leadership contest, with shadow international development secretary Diane Abbott saying some in the party are still "coming to terms" with his victory.

Wednesday's vote on the charter will not be the final time Mr Corbyn's leadership is tested in the House of Commons.

Other potential flashpoints

Nuclear weapons is an issue where Mr Corbyn's views are in direct conflict with party policy. Labour is presently committed to renewing the Trident missile system, but the party's leader is committed to opposing it, and has said he would not fire nuclear weapons if he were prime minister.

Mr Corbyn says Trident will form part of a defence review being carried out by shadow defence secretary Maria Eagle. But unless he can change Labour's policy - and a bid to get it debated at conference last month was rejected - he faces the unusual prospect of rebelling against his own party when Parliament votes on the issue next year.

Labour MPs could be given a free vote, which means they will not be bound by party lines, to avoid this happening.

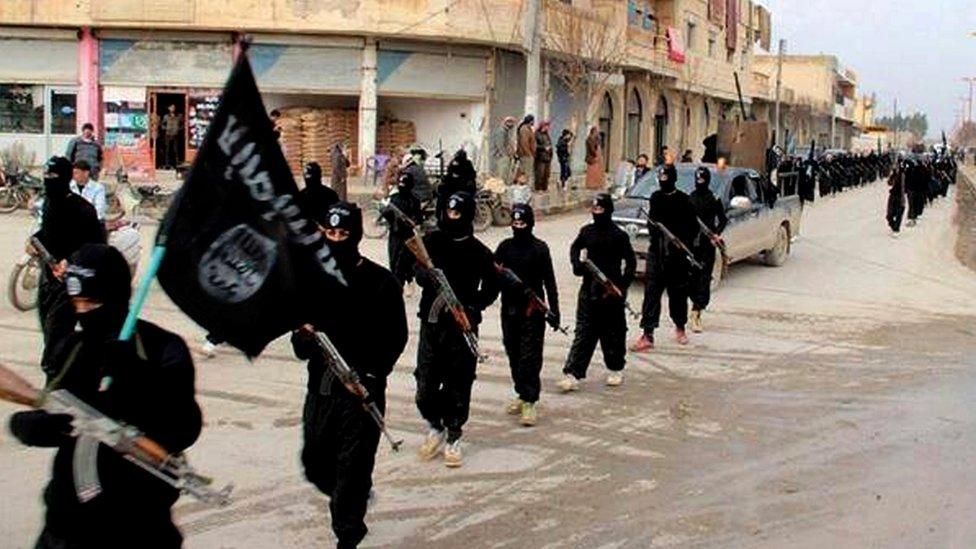

Syria air strikes

David Cameron is hoping to build Commons support for air strikes on so-called Islamic State militants in Syria. Mr Corbyn is opposed to any military intervention, but not all of his MPs - or his shadow cabinet - share this view.

The divisions were underlined by a bad-tempered Twitter exchange , externalinvolving shadow international development secretary Diane Abbott, who criticised Labour MP Jo Cox for proposing , externalmilitary action to protect civilians. Ms Abbott was branded an "internet troll" by Labour MP John Woodcock after she accused him and Ms Cox of wanting to "support Cameron in his long held desire to bomb Syria".

In his party conference speech, Mr Corbyn said "the answer to this complex and tragic conflict can't simply be found in a few more bombs".

Also at the party conference, Mr McDonnell suggested a free vote could be held, saying he did not expect consensus within the party and that he believed a vote on military action in Syria should be made "on the basis of conscience".

Welfare cap

There is a limit on the total benefits a household can receive

The government's cap on overall household benefits had already split the Labour Party before Mr Corbyn took over, with 48 of its MPs opposing the Welfare Reform and Work Bill, which will reduce the cap to £23,000 in London and £20,000 in the rest of the country, in defiance of the then interim leader Harriet Harman's order to abstain.

Mr Corbyn has said he wants to scrap the cap altogether, calling the policy "devastating". But Owen Smith, his shadow work and pensions secretary, has said Labour is only opposing plans to reduce it.

Crises averted

On some key policy issues, Labour has managed to defuse potential rows. One big one that was looming was over the EU referendum - would Mr Corbyn, who had appeared lukewarm during the leadership election, go against almost all his MPs and push for a UK exit?

Had he done so, he would have risked mutiny from his MPs and resignations from his front bench. But last month, under growing pressure to clarify his position, he told the BBC while policy was "developing" he could not foresee a situation where Labour would campaign for a "Brexit" under his leadership.

Labour appears united in its opposition to tax credit cuts, and on one of Mr Corbyn's flagship pledges - rail re-nationalisation - after the leader said he would adopt the line-by-line approach put forward by Andy Burnham in the leadership contest.

Outside the Commons

The nucleus of Mr Corbyn's support lies away from Westminster, in the party's wider membership which propelled him to his overwhelming victory in the leadership contest. Given the lack of support for the leader among the Parliamentary party, some MPs fear they will be ousted as party candidates by Corbyn supporters.

This fear has been fuelled by the creation of a new group, Momentum, external, which aims to capitalise on Mr Corbyn's victory and create a "mass movement for real progressive change".

Former shadow Cabinet member Mary Creagh is among those to suggest the group could lead to a purge of those in the centre-left of the party, and MPs voiced their concerns during Monday night's Parliamentary Labour Party meeting. Corbyn-supporting MP Richard Burgon, who was reportedly heckled at the meeting, has said his colleagues have "nothing to fear" from Momentum, which will not be "inwardly meddling".