Ten days that toppled Margaret Thatcher

- Published

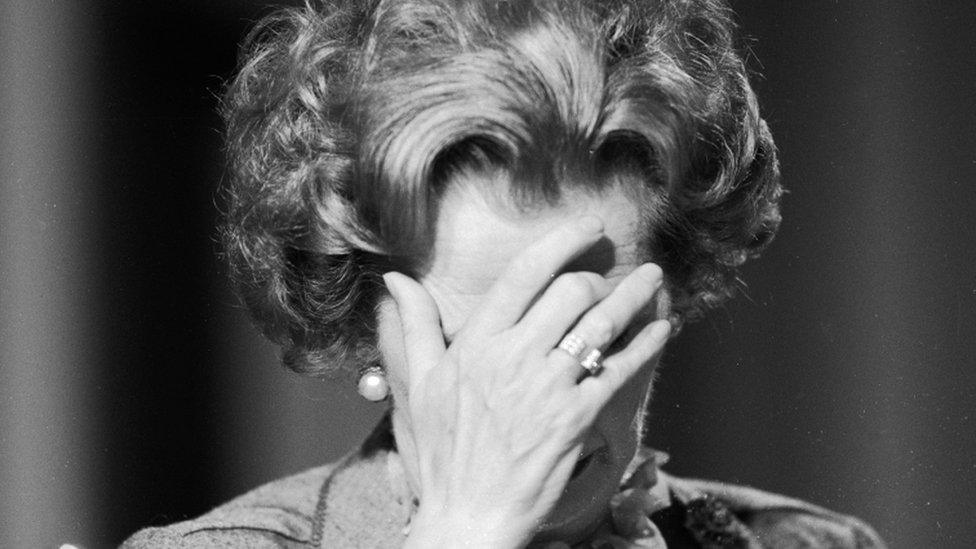

Mrs Thatcher was visibly upset as she left Downing Street after her resignation

Twenty five years ago next month Margaret Thatcher resigned as prime minister.

Yes, it is now almost a quarter of a century since the longest-serving premier of the 20th Century was unceremoniously booted out of office.

And even after all that time, her shadow still hovers over British political life: as a lodestar in the mythology of the Tory right; and as a hate figure for many on the left.

But what if she had not exited the political stage in November 1990? It is one of the interesting "what ifs" of modern British history. For there was nothing inevitable about her departure.

I have been re-examining the final days of Mrs Thatcher's government for a Radio 4 documentary to be broadcast on Sunday at 13.30 GMT.

Along with my colleague Rob Shepherd, we have spoken to many of the key figures in that final drama including Michael Heseltine, Ken Baker, John Wakeham, Ken Clarke, Chris Patten and John Whittingdale.

We have looked at the familiar issues that led to Mrs Thatcher's resignation including the unpopularity of the poll tax, the divisions over Europe, the resignation of Geoffrey Howe, and the self-inflicted mistakes during her leadership campaign.

An anti-poll tax rally in London, 1990 was one of the worst riots seen in the capital for a century

But it was splits over Europe which cemented Thatcher's downfall, with Geoffrey Howe's resignation helping to topple the leader

But in doing so, we have teased out several key moments when events could have taken quite a different tack, especially after the first ballot when Mrs Thatcher won more votes than Michael Heseltine but not enough to win outright.

No holding back

One of Mrs Thatcher's key supporters, John - now Lord - Wakeham, reveals for the first time that it was he who told her to meet the cabinet one-on-one, something which allowed them to tell her the truth - that they did not think she could win the second ballot.

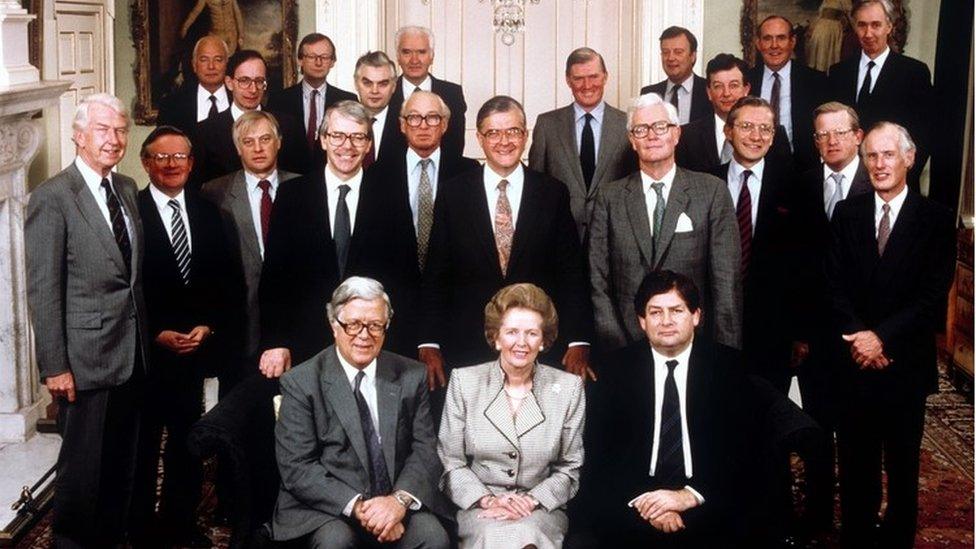

All smiles: Mrs Thatcher with her cabinet in October 1989

"I said to her 'the first thing you want to do is consult the cabinet' and she said 'I am very happy to do that' and I said 'but no, one-on-one'.

"My worry was that they were saying things to me which I was worried they didn't have the guts to say to her and I felt that they ought to say to her. She ought to know where she stood.

"I did that out of loyalty to her, not in order to get rid of her, but in order that she could make a decision as what to do. I made her know what the situation was and she then decided what she wanted to do."

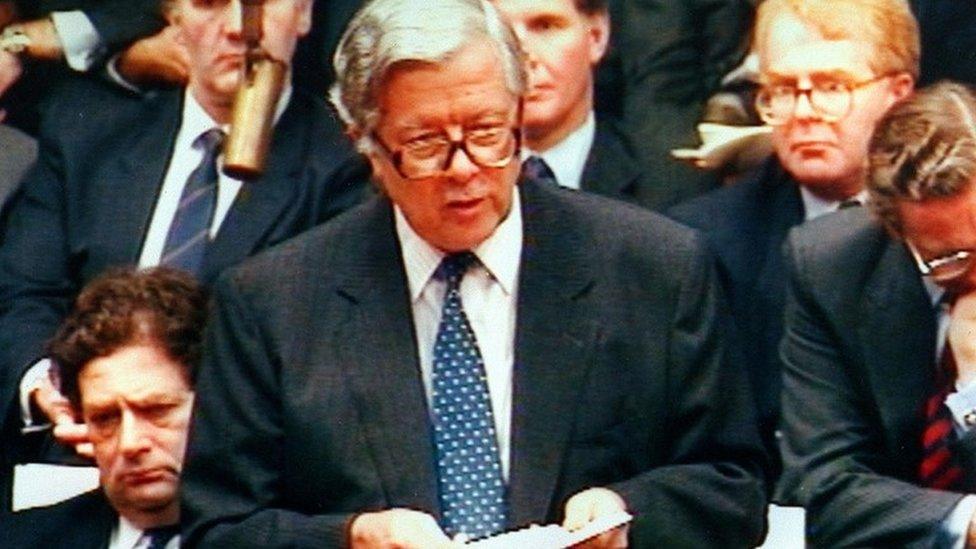

John Major would succeed as Tory leader five days after Thatcher's resignation, seeing off Douglas Hurd (r) and Michael Heseltine

Many of Mrs Thatcher's supporters believe that this was bad advice and that if she had been given the chance to rally the support of her cabinet collectively, she could have survived.

But instead she gave ministers the opportunity to tell her that she was losing support without facing the peer pressure of more loyal colleagues.

If she had fought on, the then-Chancellor John Major and Foreign Secretary Douglas Hurd would not have thrown their hats into the ring and she would have gone head-to-head with Michael Heseltine once again.

Damage limitation?

Culture Secretary John Whittingdale, who was then Mrs Thatcher's political secretary, says the leader believed she could have won the second ballot but it would have come at too high a cost.

"[What] she said to me, and I think it was a large part of her thinking for not standing, was that if she had won, it would have been so damaging for the party that it would probably have made it impossible for us to win the election."

Thatcher v Heseltine

Michael, now Lord, Heseltine reveals that after losing the first ballot, it never crossed his mind that he could stand aside - but he now admits he should have considered the option.

"There was another speech I never made and never thought about at the time. It was a year or so later that someone pointed out the option of saying 'I am not interested in winning on a technicality, I accept the verdict'. It did not occur to us to think of it. We should have done but didn't.

"It would have meant that I would have created a position in the party beyond peradventure which sooner or later someone would have had to recognise. I always believed I would be back. I never thought my political career was over, but I would not have created quite such animosity in the party."

Lord Heseltine says that if Mrs Thatcher had decided to fight on, he might have beaten her: "It is possible I would have won, but not certain. But I do know that when I heard that she was not going on, I knew there was no chance of me winning."

Thatcher's assurances

Ken Clarke reveals that Mrs Thatcher tried to win his support by promising to stand down as prime minister before the election. But during their one-on-one conversation, she insisted she could not go yet.

"She said there were things she had to do. There was no one else. She would go, she assured me. She was going to step down before the next election, but first of all she had to see us through this war against Iraq in Kuwait, and she had to get the economy back on its feet again."

'You've done enough'

Lord Wakeham reveals the decisive role that Margaret's husband, Denis Thatcher, played in persuading his wife to resign.

"I knew perfectly well that Denis wanted her to resign. He was very keen on her resigning at the time. He said 'you've done enough, old girl. You've done your share. For God's sake, don't go on any longer'."

'Over-complacent'

In happier times: Margaret Thatcher dances with Kenneth Baker at Conservative party conference in 1989

The-then party chairman, Ken, now Lord, Baker (pictured above) reveals the complacency of Mrs Thatcher's campaign chief, her parliamentary private secretary Peter Morrison.

"I went to see Peter Morrison one day and he was fast asleep in his chair. He was quite confident they were going to win. I said it was not my feeling at all. You are going to have to get out and persuade people. It was absurdly over-complacent."

10 Days That Toppled Thatcher can be heard on BBC Radio 4 on Sunday 1 November at 13.30 GMT.

- Published10 October 2015

- Published16 July 2015

- Published19 June 2015