David Cameron's complex balancing act on Europe

- Published

The UK wants to take a tougher line on EU migrants

In Britain's tense renegotiation with the rest of the EU, nothing is quite what it seems.

There are riddles and enigmas aplenty. Over dinner on Thursday, at a summit in Brussels, David Cameron will make a big pitch to find a compromise over EU migration.

In January 2013, many of us were huddled in Amsterdam to await the prime minister's first major speech on what Britain wanted from Europe.

It was postponed and delivered a short while later in the Bloomberg office in London.

Mr Cameron outlined three major challenges that would be the basis of the UK's renegotiation. Neither migration nor benefits were among them - they didn't even get a mention.

Fast-forward to November 2014 and David Cameron delivers his next big set-piece speech on Britain and Europe. The central theme is migration.

He said: "We have to maintain the faith in the government's ability to control the rate at which people come to this country.

"The British people need to know that changes to welfare to cut EU migration will be an absolute requirement in the renegotiation."

UKIP effect

So what had changed? Firstly, politics and the rise of UKIP, who in May of that year had won the European elections.

The Conservatives feared for the unity of their party and were full of foreboding about UKIP's likely impact at the general election due in 2015.

UKIP won the last European elections

Nigel Farage, the UKIP leader, said one consequence of their victory in the European campaign was that "David Cameron would have to take a much tougher negotiating stance" with Europe.

So come the election this year, a major Conservative pledge was that EU migrants would need to wait four years, external before they could claim certain in-work benefits or social housing.

Gradually this demand, which did not exist in 2013, came to be the centrepiece of the UK's renegotiation.

It was reinforced by the polls, which indicated that when it came to Europe it was the issue that mattered most to voters and could be one of the main factors that determined how they would vote in the referendum.

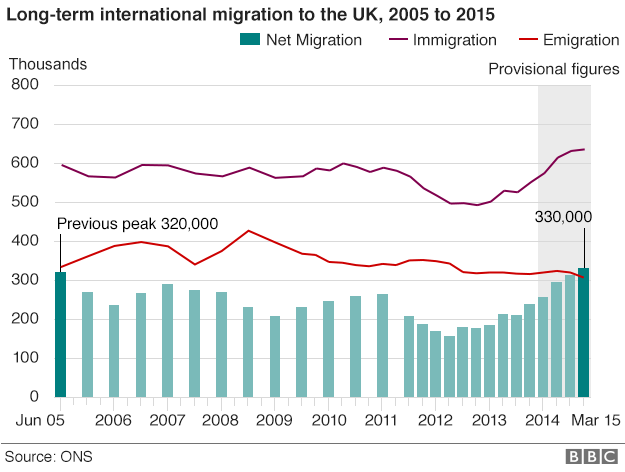

Since coming to office, the government's aim had been to demonstrate it was reducing the numbers of migrants arriving from Europe.

The history of miscalculation was widely known. When Poland joined the EU in May 2004 the then Labour government estimated that 13,000 Poles would move to the UK, external. By 2011 that figure was closer to 600,000.

So the focus of the government was on "pull factors" - what drew migrants to Britain.

Welfare factor

A key draw was identified as welfare. The prime minister spoke of "the right to work not to claim".

It has proved, however, very difficult to know how much of a pull factor benefits are.

David Cameron has promised to win significant concessions for the UK

The latest figures, external suggest that 61% of EU migrants had definite jobs to go to when they arrived in the UK. There was little evidence that migrants were coming to claim benefits.

Yet the government believed that it had strong support when it said that it was wrong for migrants to be able to claim benefits on arrival when they hadn't paid any taxes into the system.

The prime minister spoke of "people wanting grip" and of the need to "maintain faith in the government's ability to control the numbers".

For some the renegotiation came to be defined as regaining control of the UK's borders.

Yet it was proving equally difficult to reduce the numbers coming from outside the EU, where the government had control of who entered the country, as coming from inside it.

For the year ending June 2015, net migration of EU citizens to Britain was up 53,000 to 183,000. But for non-EU citizens, the numbers also rose by 39,000 to 196,000.

When the government put changes to welfare at the centre of its renegotiations there were warnings that it would contradict the principle of free movement and discriminate between UK and other EU citizens.

Such a step would be open to legal challenges and it would stoke strong opposition from countries in Central and Eastern Europe. And they could block making any changes to the EU treaties.

Yet to the surprise of some other European leaders the prime minister has pushed on in the face of opposition.

Conflicting signals

Ahead of Thursday's summit there have been conflicting signals that the government was backing off making this key demand whilst also insisting the idea remained on the table.

Some of those in Brussels who have been party to the negotiations have long suspected that the government might stage a row in December in order to demonstrate to the voters that it had fought a hard campaign for Britain's interests.

Others had questioned whether there had been a calculation that the EU, reeling from successive crises, might be more willing to give the UK what it wanted.

If so it would be a misreading of the dynamics of European politics.

It has become almost a cliché in Brussels that no crisis should be allowed to go to waste and that the response to a faltering single currency or to migrants or to terror is to deepen integration.

It has happened over the migrant crisis.

With the suspension of passport-free travel in parts of the Schengen area, the commission has reacted by proposing a new European border and coastguard agency which it could deploy to defend the common European frontier, whether countries liked it or not.

There may well be resistance to the idea when it is proposed this week but if it were backed it would involve one of the largest transfers of sovereignty to Brussels since the launch of the single currency.

I digress, but however embattled the EU may feel it would be unwise to doubt its determination to defend the principle of freedom of movement.

On migrants and welfare there may well be a compromise.

Gut response

Commentators have been suggesting for months that the answer to the accusation of "discrimination" lies in the UK applying a residency test for in-work benefits that would apply equally to EU migrants and returning British expats.

Angela Merkel and Francois Hollande will have to be persuaded of the UK's case

Or it could be that the UK settles for an "emergency brake" on migrants when the numbers arriving put pressure on social services.

And here is another layer to this complex negotiation. The Office for Budget Responsibility says that changes to budget rules are "unlikely to have a huge impact" on the numbers of migrants.

So if David Cameron wins a deal on migration - and that is looking unlikely to be until February at the earliest - what will the voters make of it?

Will they see it as the negotiation for "fundamental change" as promised?

Will they focus on what has been agreed; less regulation, an opt-out to "ever closer union" and protection against eurozone countries damaging key British interests?

Will voters focus on the detail or will in the end this vote be determined by something far less tangible - a gut response to the EU, or to migration that may well pick up again in the spring?

The strange aspect to this argument about migrants and benefits is that neither side of the debate believes it is the core issue.

Those inclined to leave the EU insist that the referendum is about the return of democratic powers.

Those who want to remain inside the EU say it is about economic security and that the "leavers" will have to describe what life would be like outside. Layers of complexity.

UK's EU referendum in-depth

- Published14 December 2015

- Published14 December 2015

- Published8 December 2015