Corbyn and Kinnock: Leading Labour in difficult times

- Published

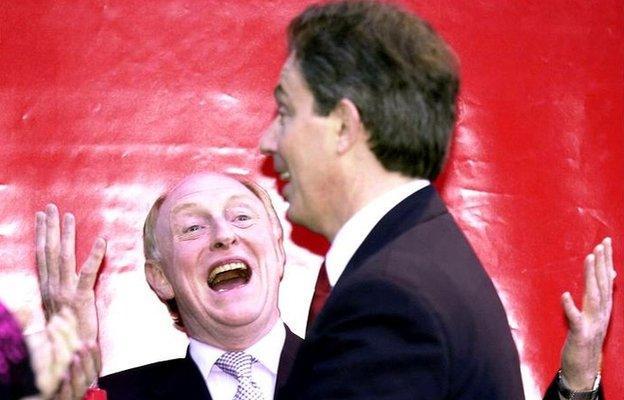

Neil Kinnock celebrates with his wife Glenys after winning Labour's 1983 leadership contest

When Neil Kinnock was elected Labour leader in the wake of the party's devastating 1983 election defeat, he told me privately that while he did not believe it possible for his party to recover sufficiently in the next four years, "if we don't win in 1987 it won't be through any fault of mine."

And so it proved. Neil Kinnock took on the worst possible job in British politics, leading a raggle-taggle movement that was more at war with itself than with the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher it was meant to oppose, and by dint of firm leadership he did what he could to present his party as one that was fit to govern.

Yes, he failed twice, in 1987 and 1992, but he did the groundwork that paved the yellow brick road for Tony Blair. And no, those two defeats were not his fault.

The situation Kinnock faced all those years ago now seems extraordinarily similar to that ahead of Jeremy Corbyn today.

The Labour Party was thrashed in this summer's general election, as it was then. An ascendant Tory party with an unexpected overall majority is revelling in its ability to do what it likes in government without the brakes of an effective parliamentary opposition in the House of Commons. Just as Thatcher found it.

Neil Kinnock paved the way for Tony Blair

Labour MPs are divided among themselves about policy and principle and what to do next about anything.

And just as the Social Democratic Party in the early 1980s was limbering up towards a potential for real power, so there is talk again of that fundamental split on the left between the Socialists and the Social Democrats to resolve the question that has never been answered in the Labour Party, then or now.

Different politics today

All this against a backcloth of an uncertain world, the growing threats of terrorism, economic inequality, how to meet the defence budget and how to pay the heating bills for global warming.

And yet, despite these similarities, the politics of where we are today for Mr Corbyn as he reaches the 100th day of his leadership is profoundly different from that of yesteryear.

A charming illustration of that was provided by Harriet Harman, for many years with a hand on the helm of the Labour Party, who recently tweeted a photocopy of her 1983 constituency report, external to illustrate the perceived historical coincidences.

She wrote of the party's political collapse, the loss of the ideas battle, the threat of the political wilderness and the dangers of a drift to the right. But it was all as out of date as the typewritten script of her document.

Labour MPs may be split among themselves but the greater division is between them and the Labour Party members.

Labour MPs may be divided over Mr Corbyn but the leader is popular among the party's members

The one counter to the despair of today's bewildered Labour MP lies in the number of those who have joined the party since the general election and the subsequent choice of Mr Corbyn as leader.

They are truly extraordinary: 183,000 between May and September and at least another 50,000 since. The Labour Party hasn't known anything like this since before Tony Blair.

Jeremy Corbyn's first 100 days as leader

12 Sep: Elected leader of the Labour Party, winning a landslide 59.5% of the vote, after starting the contest as the rank outsider

14 Sep: Unveils his shadow cabinet, which includes his left-wing ally John McDonnell as shadow chancellor

16 Sep: Uses his first PMQs as leader of the opposition to ask David Cameron questions emailed to him from the public

12 Nov: Sworn in to the Privy Council, the historic group which advises monarchs, though Labour did not confirm whether Mr Corbyn, a lifelong republican, knelt before the Queen

2 Dec: Clashed with Mr Cameron as the Commons debated the case for air strikes in Syria, but did not impose his opposition to military action on Labour and allowed his MPs a free vote

11 Dec: Attended a fundraising dinner for the Stop the War coalition, despite calls from some of his MPs not to attend

Mr Corbyn was Labour's most rebellious MP during the party's 13 years in power, defying the whip 428 times

In principle, things really can only get better. The practical problem is that Mr Corbyn has to sort out how to harness the democratic authority he gained from his triumphant election success to a degree of parliamentary respectability.

Someone who has enjoyed the luxury of principled rebellion over three decades as an MP, solely because no political responsibility rested upon his personal righteousness, has somehow got to demonstrate that he now concedes he understands the consequences of every stand he takes.

If he can find a route to do that, his political authority would be enormous, his MPs would be obliged to fall into line and the Labour Party could begin to offer a coherent opposition. The doubts are about whether he can do it.

At a recent gathering of the old left, in its historic cultural home, The Gay Hussar in Greek Street, the "Goulash Co-Operative" - formed to try to buy the restaurant from its current owners - held a celebratory lunch.

To the tune of the folk song There is a Tavern in the Town (if you're unfamiliar with it, think of the children's song Heads, Shoulders, Knees and Toes, which is sung to the same tune) they sang four verses of a newly penned pastiche, led by the impressive bass Welsh Valley thundering tones of one Neil Kinnock.

"We'll put the Ed Stone up in Soho Square.

"And blame it all on Tony Blair," they sang.

I asked Mr Kinnock what he would do if he was Jeremy Corbyn. He said he wouldn't start from here.

Julia Langdon is a political journalist, broadcaster and author. She is the former political editor of the Sunday Telegraph and Daily Mirror.

- Published16 December 2015

- Published14 September 2015

- Published12 September 2015

- Published12 September 2015

- Published24 September 2016