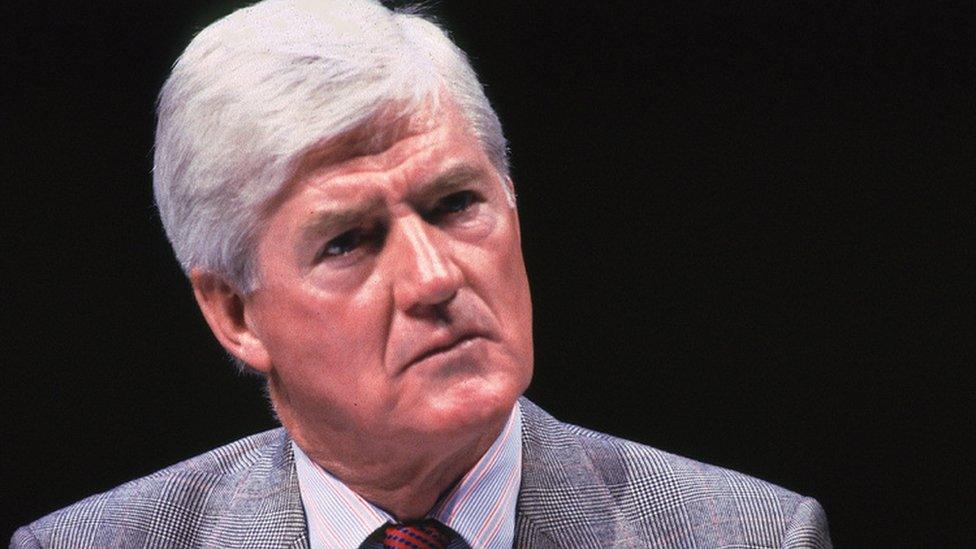

Obituary: Cecil Parkinson

- Published

Lord Parkinson has died aged 84 after a long battle with cancer

As Conservative Party chairman in 1983, Cecil Parkinson was given much credit for his party's landslide election victory that year. But by the time of the party conference in the autumn, the scandal over his affair with his secretary Sara Keays - who was pregnant with his child - forced his dramatic resignation.

Humble beginnings

Cecil Parkinson - picture here with his family - joined Parliament in November 1970, as the MP for Enfield West

Cecil Parkinson was a political shooting star, who rose from humble beginnings to a point at which many saw him as a future prime minister - until the scandal that engulfed him.

He had previously succeeded as a businessman, a government minister and as the Conservative Party's most attractive, high-powered public relations man. He possessed charm, flair for organisation and political sophistication.

Born at Carnforth, in Lancashire, Cecil Parkinson was the son of a railwayman and in his youth he was left-wing, a pacifist and considered becoming a clergyman.

He attended the local grammar school before studying at Cambridge, where he graduated with a third in law. At this point his interest in politics seemed to have disappeared and he moved south to work in the City of London, where he became a chartered accountant.

It was his marriage - in 1957 to Ann Jarvis, the daughter of a rich builder in Harpenden, Hertfordshire - that pointed him in the direction of the Conservative Party. His wife was an ardent Conservative, and her father helped to set up Lord Parkinson in the business world.

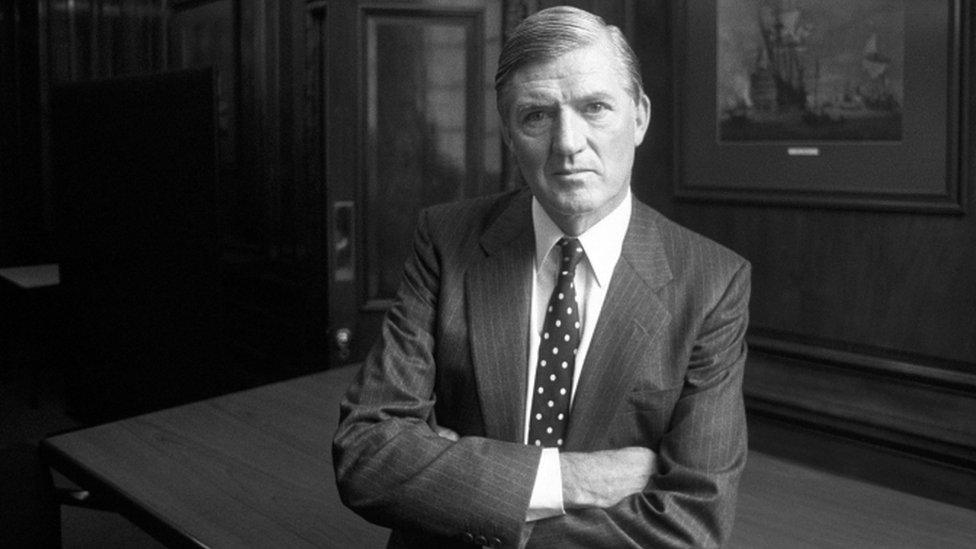

Rising through the ranks

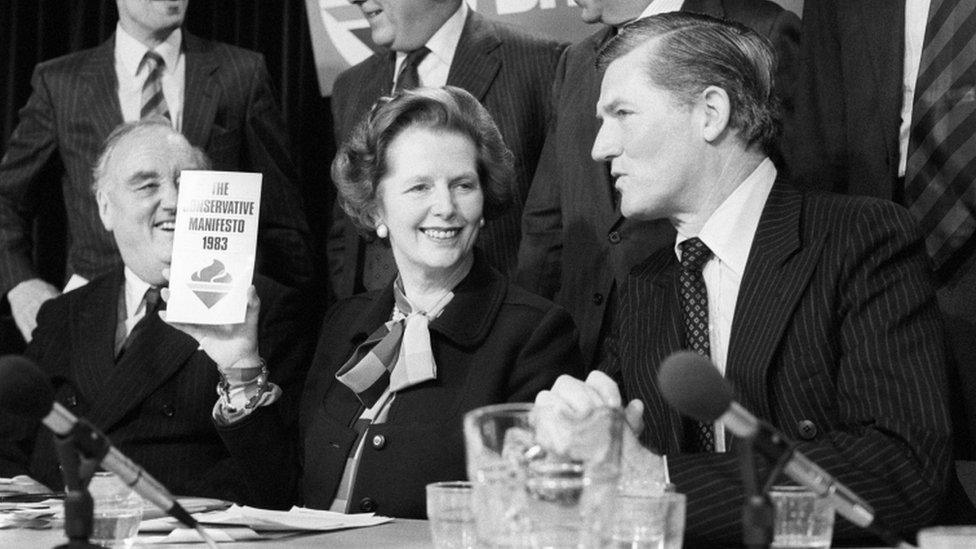

Cecil Parkinson was regarded as one of Margaret Thatcher's closest political allies, and instrumental in the party's 1983 election victory

Elected to Parliament in a by-election in 1970, he represented the constituency of Enfield West and subsequently Hertfordshire South and Hertsmere, seats which were affected by boundary redistributions.

In 1974 he was made a whip and promoted to spokesman on trade two years later. Following the party's election victory in 1979 he was appointed a junior minister at the Department of Trade.

At that point he was still virtually unknown outside Westminster and not that well-known inside it, but all that changed in 1981 when Mrs Thatcher made him party chairman - an appointment which catapulted him into the top ranks of the party.

Read more about Cecil Parkinson

He was also given the post of Paymaster General and a seat in the cabinet, and a year later he became chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster.

These rapid promotions led many to see him as a pawn of the prime minister, especially when he was made a member of the "War Cabinet" during the Falklands crisis.

But he proved that he, better than anyone else, could go before the television cameras and - in a relaxed, reasonable and appealing manner - tell the nation what the government was up to; something he did to great effect.

Lord Parkinson's greatest triumph, however, was the 1983 election campaign, which was a model of discipline, timing, co-ordination and organisation. For this he was rightly given most of the credit, and when the new government was formed he was given the post of trade and industry secretary.

Political downfall

Mr Parkinson was the fourth Conservative MP at the time to hit the headlines for scandal since Mrs Thatcher took office in 1979

It was reported that Mrs Thatcher intended to make him foreign secretary as a reward for masterminding the victory, had it not been for what came next. His secret affair with Miss Keays, and the revelation that she was pregnant with his child, became public knowledge - during the Conservative Party's 1983 autumn conference.

He issued a statement admitting that he had offered to marry Ms Keays at one time, but added that he had later changed his mind, and was staying with his wife. He promised to make adequate financial arrangements for the child, and he firmly denied he was going to resign.

When he addressed the party conference he got a sympathetic, if somewhat lukewarm, reception. He seemed to have survived the storm.

Sara Keays, pictured with her baby, made a public statement to "put the record straight" about her relationship with Cecil Parkinson

But it was Ms Keays' statement to The Times - designed, she said, to "put the record straight" on their relationship - that ultimately resulted in his demise. It appeared on the final day of the conference, and revealed facts which Cecil Parkinson's statement had omitted. He immediately resigned his government post, though he remained an MP.

An influential figure with Mrs Thatcher, he was regarded as one of her close private friends. Over the next few years there were regular reports that she was anxious to bring him back into the government, but his return was opposed by some senior ministers.

It was probably delayed also by Sara Keays, who made sure she and her baby daughter remained in the public mind. She wrote a book, published in the autumn of 1985, giving details of her 12-year affair with Lord Parkinson, and implying that he had told her government secrets. Scotland Yard was asked to investigate, and later the Director of Public Prosecutions announced that no action was being taken.

Ms Keays's book was serialised in newspapers. She later gave magazine interviews and appeared on television. Lord Parkinson was also hit by another personal issue: his eldest daughter developed a heroin addiction.

Political comeback

However, he was re-elected in 1987 with an increased majority and brought back into the cabinet as energy secretary, to prepare the electricity industry for privatisation.

Two years later he took over transport, which had become something of a political hot seat, after much criticism of Paul Channon's handling of a series of rail and air disasters, and particularly airport security.

Lord Parkinson became Conservative Party chairman for a second time in 1997, under William Hague's leadership

Almost inevitably he, too, suffered criticism, but he did manage to win from the Treasury a substantial increase in the money available for improving Britain's roads and railways.

One of his arch-critics was Labour's chief transport spokesman, John Prescott, whom Lord Parkinson denounced for his attitude to transport tragedies. He was a political vulture, he said, with an almost obscene passion for television appearances.

Lord Parkinson resigned as soon as John Major succeeded Mrs Thatcher as prime minister, but he said he was delighted the party had elected such a fine leader to succeed her, and promised him his total support from the backbenches.

Lord Parkinson stepped down as an MP in 1992 and was elevated to the House of Lords.

While that might have been expected to be the end of his career in frontline politics, he returned to the fray in 1997 when William Hague asked him to rerun his previous role of party chairman after their election defeat.

But in the end that role - where two of the younger Conservatives who worked for him were George Osborne and David Cameron - only lasted until 1999 when he retired and, barring the occasional media interview, was rarely back in the political spotlight.

- Published25 January 2016