What is the row around PIPs all about?

- Published

At the heart of the row between the now former work and pensions secretary Iain Duncan Smith and his government are PIPs - Personal Independence Payments.

But why have they become so controversial?

What are PIPs?

PIPs are benefit payments made to help people aged 16 to 64 cope with the extra costs they face due to ill health or disability. Not means-tested, they are gradually replacing Disability Living Allowance (DLA).

Nearly 700,000 people currently claim PIP, with another 1.5 million still to be reassessed.

Who gets it?

DLA was commonly based on self-assessment, whereas eligibility for PIP includes a test carried out by Atos or Capita on behalf of the government. Money is allocated according to a points system and eligibility is kept under regular review.

The criteria for PIP were already stricter than DLA - for example, in the past someone was considered to be "virtually unable to walk", and therefore eligible, if they could not walk more than about 50 metres. Under PIP, that was dropped to 20 metres, excluding, at the government's estimate, more than 420,000 people.

Ministers wanted to make the criteria stricter still and that desire is at the crux of the current row.

What is PIP for?

There are two components - daily living and mobility - and eligibility is based on ability to carry out 12 activities, including eating and drinking, washing, going to the toilet, communicating and getting around.

The more severe someone's needs the more they will receive - up to a maximum of £139.75 a week.

The money can be spent on a wide range of things. The mobility element often goes towards specially adapted cars, scooters or wheelchairs, paid for via the Motability scheme. The daily living element can cover anything from a prosthesis to specially designed utensils, hand rails and toilet seats.

What did the government want to change?

The plan was to reduce the weighting given to two of the 10 criteria for the daily living element - dressing and managing toilet needs. So, instead of someone who needs grab rails to use the toilet receiving two points, they would have only received one.

That single point difference could have meant an individual getting less money, or losing PIP altogether if it put them below the points threshold for qualifying.

Why did it want to do that?

An independent review, external carried out for the Department for Work and Pensions found that "a significant number of people are likely to be getting the benefit despite having minimal to no ongoing daily living extra costs".

The department says it reviewed a "number of cases" and in 96% of them the "likely ongoing extra costs of daily living were nil, low or minimal" - for example, because many of the aids and appliances which people are currently getting points for are provided free by the NHS and councils, or could be bought cheaply.

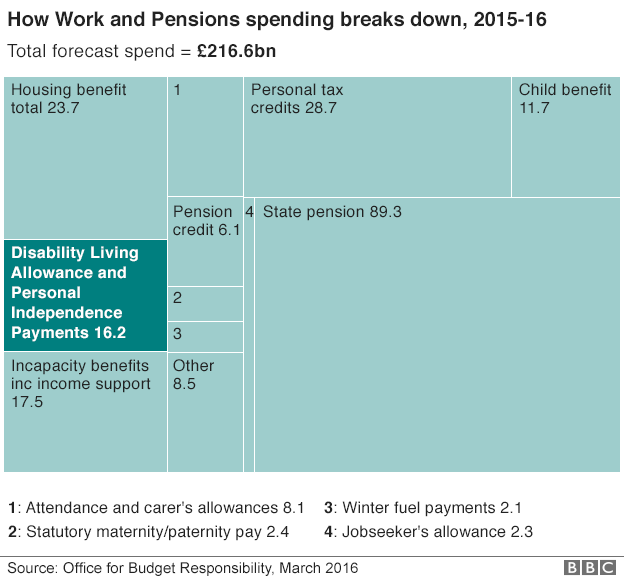

Number 10 also says the cost of PIPs is rising by around a billion pounds a year and needs to be brought under control.

Was PIP supposed to save money?

Yes. In his first Budget in 2010, George Osborne made reforming DLA a priority.

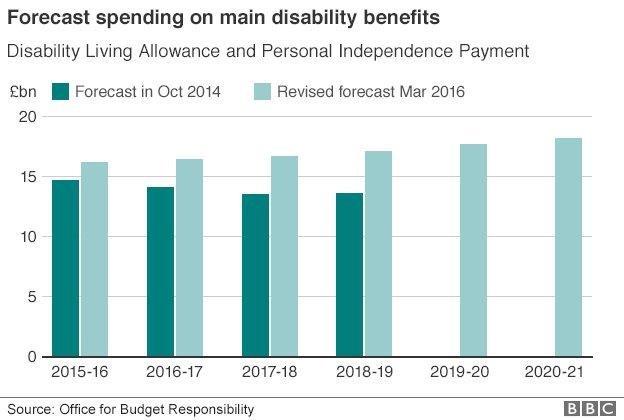

Four years later, in October 2014, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast that spending on disability benefits between 2015 and 2019 would total £55.9bn. By March 2016, that figure had risen to £66.4bn.

The switch to PIP was designed to save money - something sources close to Mr Duncan Smith are continuing to insist it will ultimately do - but things are not as simple as that.

Those same sources have told the BBC the problems are "to do with people transferring to PIP from DLA. They are sicker than the DLA system said they were."

The OBR said the rising costs were because of higher-than-expected caseloads - and people getting more money than ministers had predicted. The average payout is now £100 a week, 14% higher than expected.

Costs have also risen because claimants are being increasingly successful in appealing against officials' decisions, often helped by charities.

What impact would the latest changes have had?

Not everyone would have lost out, and those who did would have only lost cash as and when their conditions were reassessed.

However, charities said up to 640,000 people would be affected by 2020, each standing to lose up to £100 a week.

Labour said the changes would have removed the ability of many people to live independently.

And of course, the loudest critic of all has been Mr Duncan Smith, who said the decision to "juxtapose" the changes with tax cuts for the better off in the Budget was the final straw.

For its part, the government says making the criteria stricter would have saved £1.2bn a year and made the system "fairer". More broadly, it puts the changes in the context of the planned introduction of Universal Credit - the new single monthly payment of benefits and tax credits due for roll-out from 2017 - under which it says some people will be better off.

What happens now?

The proposals have been shelved.

However, the government said just a few days before the Budget that it wanted to save a further £4.4bn from the UK welfare bill. Asked how the chancellor would cover the shortfall created by not going ahead with the PIP changes, Downing Street suggested the issue would be looked at in the Autumn Statement.

Number 10 has, though, stressed that PIP will still have to be reformed in the future as the cost is "unsustainable."

More broadly, there is the political fall-out. What damage has been done to George Osborne and indeed, David Cameron, and the impact Mr Duncan Smith's resignation will have on the EU referendum campaign, all remain to be seen.

- Published21 March 2016

- Published17 March 2016

- Published17 March 2016