Pensioners: Are the untouchables still untouchable?

- Published

David Cameron has made a clear commitment to protect and reward Britain's pensioners for as long as he is prime minister. The "triple lock" on pensions, the winter fuel payment, free bus passes, TV licences, prescriptions and eye tests, all guaranteed "no question".

It's a promise that comes with a huge price tag, though. A hastily withdrawn official report from the Government Actuary's Department last year suggested the "triple lock" - raising the state pension annually by the highest of inflation, earnings or 2.5% - has added £6bn extra a year to the benefits bill.

That is a massive additional sum - particularly at a time when the government is insisting the overall welfare budget be reduced by £12bn.

Michael Buchanan: Pensions stance creates budgetary mayhem

Kamal Ahmed: Osborne 'boxed-in' by policy pledges

Laura Kuenssberg: No more welfare cuts, for now

Almost every attempt to find the savings within the benefits bill has ended in tears. Cuts to tax credits have been shelved, disability benefits are now protected and the new Work and Pensions Secretary, Stephen Crabb, has promised there are no further planned cuts to the welfare budget.

Even the chancellor's raid on housing associations and local authorities by cutting housing benefit has come back to haunt him, with the postponement of the policy in respect of supported housing projects.

The government has talked itself into a corner and inevitably, questions are being asked as to whether the prime minister's straight-to-camera promise not to touch pensioner entitlements can be sustained.

Price of broken promises

This afternoon in the House of Commons, Conservative MP Stewart Jackson said pensioner benefits needed to be reassessed. "It's wrong morally I believe to make large-scale transfer of wealth from the young to the old, and I think there has to be a consensus," he said.

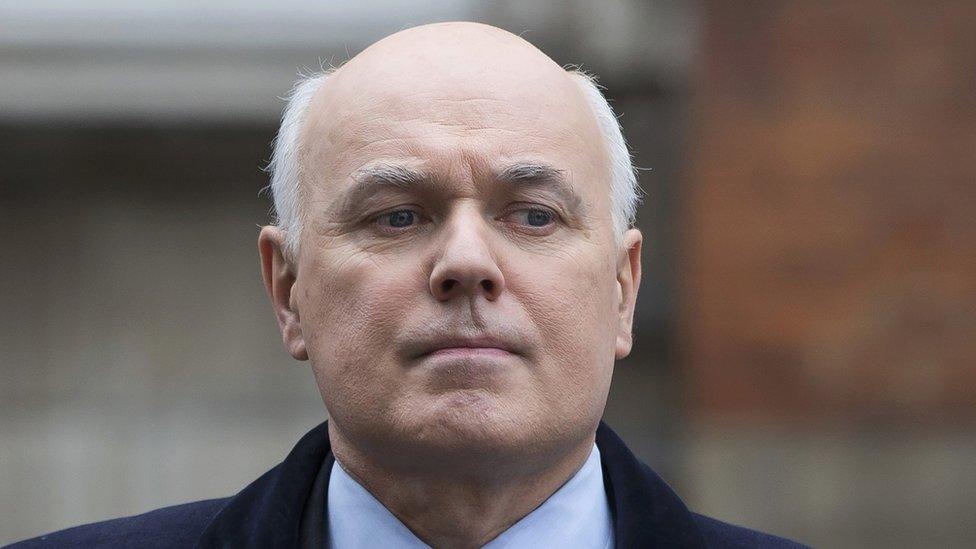

Before his resignation, Iain Duncan Smith had argued that universal pensioner benefits should be scrapped in favour of a means-tested system. Winter fuel payments and other pensioner benefits cost close to £3bn a year and the Sun newspaper was among those campaigning to "ditch handouts to rich OAPs", external.

Iain Duncan Smith had wanted a means-tested system for assessing pensioner benefits

But Mr Cameron, aware of the political price paid by former Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg when he went back on his promise to oppose student fees, is adamant that his government will not break its pledge to Britain's pensioners.

This special protection means that, once housing costs are considered, median pensioner incomes are higher than non-pensioner incomes. While young people tightened their belts during the downturn, the over-65s were getting richer.

The result of that is that poverty among pensioners is now lower than among people of working age. It is quite a turnaround - in the 1960s, about 40% of pensioners were living in poverty, compared with less than 10% of under-65s.

The pensioner has become a totemic force in British politics. They vote and their numbers are growing. The over-65s have become almost untouchable.

As David Cameron puts it, "I want older people across this country to know this: for all the decades you've toiled, for the years you've done the right thing - for the rest of your days you will have dignity and security."

75p cheques

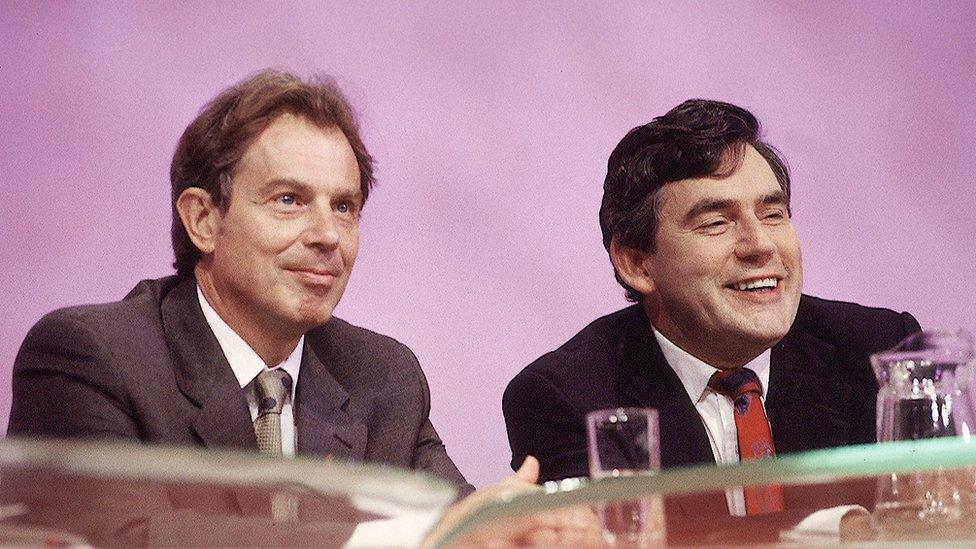

Labour raised the state pension by just 75p a week in 1999 - Tony Blair later admitted it was possibly his biggest mistake as prime minister

The political consequences of getting pensioner policies wrong can be highly damaging.

In 1999, New Labour made what Tony Blair regards as one of the greatest mistakes of his premiership when the basic state pension was increased by inflation - a "derisory" rise of just 75p a week.

It may have been a rise in line with the cost of living, but the government found itself attacked from all sides.

Many Labour supporters blamed Margaret Thatcher for breaking the link between pensions and earnings, and the idea that their own party should continue with the inflation link led to quite a few members sending cheques for 75p to Gordon Brown at the Treasury.

To add insult to injury, the department cashed them.

Labour did eventually restore the earnings link but the coalition went further, introducing the "triple lock".

How sustainable?

So pensioners are a powerful lobby group, but the question of whether their level of protection is too great has burst out into the open.

A committee of MPs has launched an inquiry into "intergenerational fairness" - investigating the extent to which government policies, such as the "triple lock", are leading to inequity between the young and old.

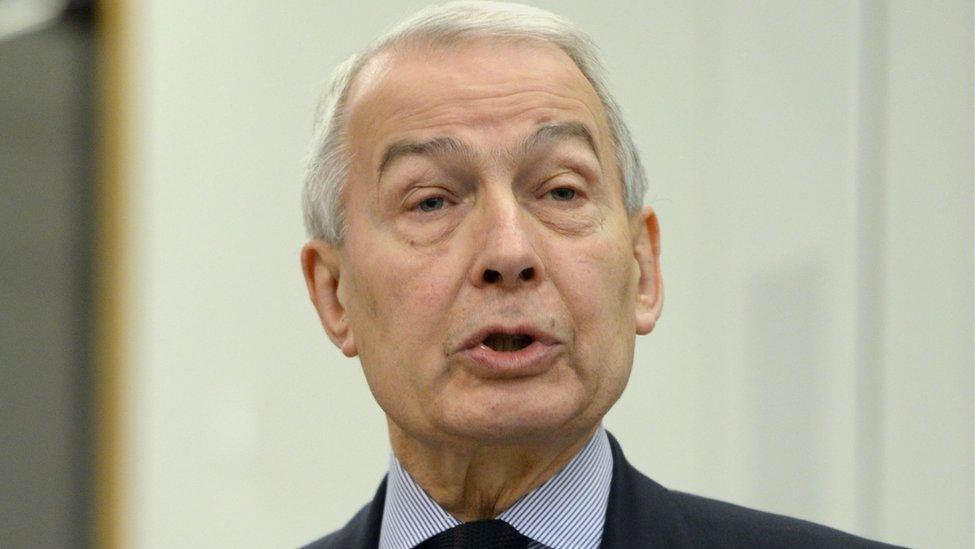

Labour's Frank Field chairs the work and pensions committee

"Is it fair and affordable to divert a large and growing sum of public expenditure towards pensioners - regardless of their circumstances - while mainly poor families with children face year-on-year restrictions on their income?" asks committee chair, the veteran Labour welfare reform campaigner Frank Field.

"Can the "triple lock" pension increase pledge be sustainable? Or are these policies necessary to guard against pensioner poverty?"

The committee points out that the group born in the middle of the baby boom (between 1956 and 1961) has been forecast to receive from the welfare state 118% of what they contribute, while recent research shows that younger people are on course to have less wealth at each point in their lives than earlier generations had acquired by the same age.

However, the basic state pension is still far from generous - the most you can currently get is £115.95 per week - and older people must bear the brunt of social care cuts with attendance allowance rates (which help with personal care if you're disabled and aged 65 or over) frozen in the most recent Budget.

Many would argue that the reduction in pensioner poverty is a cause for celebration, not jealous sniping.

If David Cameron refuses to entertain any change of tack on the commitment to "triple lock" and other pensioner benefits while protecting other spending, the question remains: where is he going to save the missing billions?