Green's Natalie Bennett on leadership, hugs and 'stupid' questions

- Published

Natalie Bennett: Green Party 'clearly different' to Corbyn's Labour

As the Green Party of England and Wales prepares to unveil a replacement for Natalie Bennett, who is standing down after four years as leader, she reflects on life in the media spotlight - and what she plans to do next.

The phrase "rapid rise through the ranks" is a standard line in profiles of political leaders. But it's rarely as speedy as in Natalie Bennett's case.

The Australian-born former Guardian journalist woke up on New Year's Day 2006 and decided she wanted to do something to change the world.

After pondering her options (should she get involved with an NGO or the UN?) she joined the Green Party. Within six short years she had become its leader.

Three years after that she was sharing a stage with the prime minister and other party leaders in a televised general election debate.

Her sudden arrival on the frontline of British politics was all the more remarkable because she had never won an election, other than the one that had made her party leader.

Her first aim when she took on the job was to insert the Green Party - routinely ignored or patronised by the mainstream media - into the national conversation.

Natalie Bennett had a tough time on the Today programme

But when media outlets finally began calling, on the back of a surge in support for the party, she sometimes found it difficult to get her message across in a suitably snappy way.

Her vision for the party was to show how "economic and environmental justice are indivisible", she explains, "the idea that tackling environmental problems isn't an add-on luxury".

It was "not a easy concept to get across", she confesses. "I still don't think I've got the 12 second soundbite. But I am going to keep working on it."

"It's a classic Shakespearean thing," she says of her struggles with the broadcast media. "It's both my strength and my weakness that I answer the question."

But, she adds, "when you get asked a stupid question, it's rather hard to know what to do at that point. And I guess I get tangled up in my desire to answer a question, even when it's a really stupid question".

Did she get asked a lot of stupid questions?

"Yes."

Asked for an example, she ponders for a minute, before highlighting an interview with the BBC's very own John Humphrys, which led to her having "to spend time, valuable peak time, explaining how the interviewer got the question wrong. And listeners don't particularly like that because it's all technical and boring and you are arguing with the interviewer but if it's entirely on the wrong track you have to".

The Green leader apologised for her 'brain freeze'

She says she has some sympathy with Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, who has also attracted criticism for broadcast interviews in which he has deviated from the usual prepared soundbites.

"The focus on the individual is a problem for British politics and it's very uncomfortable when the focus is on you," she says, arguing that the media in continental Europe are focused more on policies than personalities and trivia.

"I am not complaining - you have to work within those limits," she adds, but she believes British politics is "broken" and the media must take its share of the blame.

"There should be some pressure on the journalist to ask better, more sensible questions," she argues.

There was nothing particularly stupid about the question that prompted her darkest moment in a radio studio, however, when she struggled over several excruciating minutes, punctuated by coughing fits, to answer a question from LBC's Nick Ferrari on her party's housing policy.

She was quick to hold her hands up afterwards, apologising to supporters and blaming her sub-par performance, in the heat of the general election campaign, on "brain freeze".

"That was a very tough moment. And of course you take a bit of a punch to the stomach.

"But then a few weeks later I was up on the leader debates, able to look David Cameron in the eye and challenge him about his failure to welcome Syrian refugees to Britain, and that was one of the best moments.

"My great problem on that day was that I was in no way well enough to actually be doing anything. I'd had about three and a half hours sleep and I'd been throwing up most of the night. I should have just pulled the day but that's partly a function of how we got to that point.

"We weren't used to getting a lot of media attention and it was very, very hard to turn media attention down."

A moment that will inspire a new generation of female politicians?

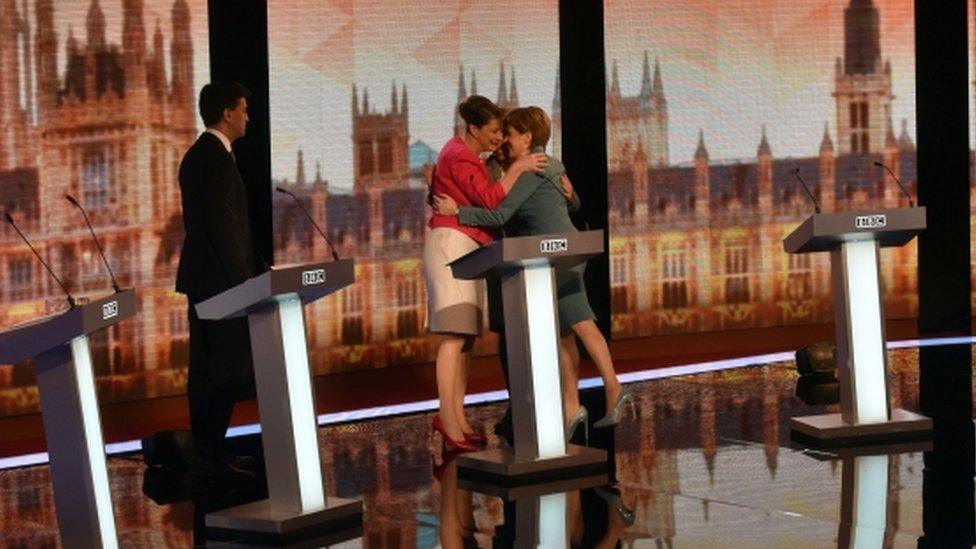

One of Ms Bennett's proudest moments came at the end of the BBC leaders debate when she joined Plaid Cymru leader Leanne Wood and Scotland's First Minister Nicola Sturgeon in a "group hug", while Labour leader Ed Miliband looked on awkwardly.

This felt like a watershed moment for women in politics, she says, sending out the message "that politics can not just be 'dog eat dog', it can be people agreeing on some things and disagreeing on others but supporting each other".

As a lifelong feminist, she is particularly pleased to have been told by "lots of young women" that they had been inspired by the "group hug", which she stresses had not been planned in advance.

"I hope and think that that moment really, in 15 years' time, 20 years' time, we might see a whole crop of MPs down the road who will reference that moment as the time they decided they were going to try and get there."

Ms Bennett's decision to pitch for the anti-austerity vote, positioning the Greens as a left-wing alternative to what was then Ed Miliband's Labour Party, struck a chord with idealistic young people who felt alienated by mainstream politics, and led to a surge in party membership.

But then Jeremy Corbyn came along and shifted Labour firmly to the left, inspiring idealistic activists to join his party in numbers the Greens could only dream about.

Would Corbyn supporters feel at home in the Green Party?

Hasn't the Green Party, which had a mixed set of results in May's elections, losing four councillors in England and failing to make progress in Wales but getting its best ever result in London, been crowded out of the picture by Labour?

Ms Bennett insists this is not the case, arguing that there is a "very clear distinction" between the Greens and Labour on a range of issues - from nuclear weapons to fracking - and that voters know exactly what they are getting when they vote Green.

But she is also open to the idea of a "progressive alliance" at the next general election, with local Green Parties potentially making electoral pacts with Labour, Plaid Cymru, the SNP or other parties who broadly share their outlook.

Leadership advice

She remains a passionate advocate of electoral reform. The Green Party fielded a record number of general election candidates in 2015, standing in 93% of constituencies, and gaining more than a million votes. By rights, she argues, the party should have 25 MPs. She believes the case for scrapping what she sees as Britain's outdated first-past-the-post electoral system is gaining ground in the country.

She says she has had an "amazing" four years as leader, and has no regrets, believing the party is in better shape now, having quadrupled its membership and gained a foothold in the national debate on issues such as welfare and the economy, than when she took over.

But she is also keen to stress that she will not be leaving politics.

"I'm aiming to turn former leader into a role in its own right, to keep travelling the country, supporting local parties, doing media. Leadership is a role we can share around. It's not you become leader, that's the pinnacle, and then you disappear."

Asked if she has any advice for the next leader, she says trust the party membership.

Anything else?

"Work out how to answer stupid questions," she laughs. "I still don't quite know the answer to that one myself."

- Published2 September 2016

- Published16 May 2016

- Published7 May 2016

- Published16 April 2015