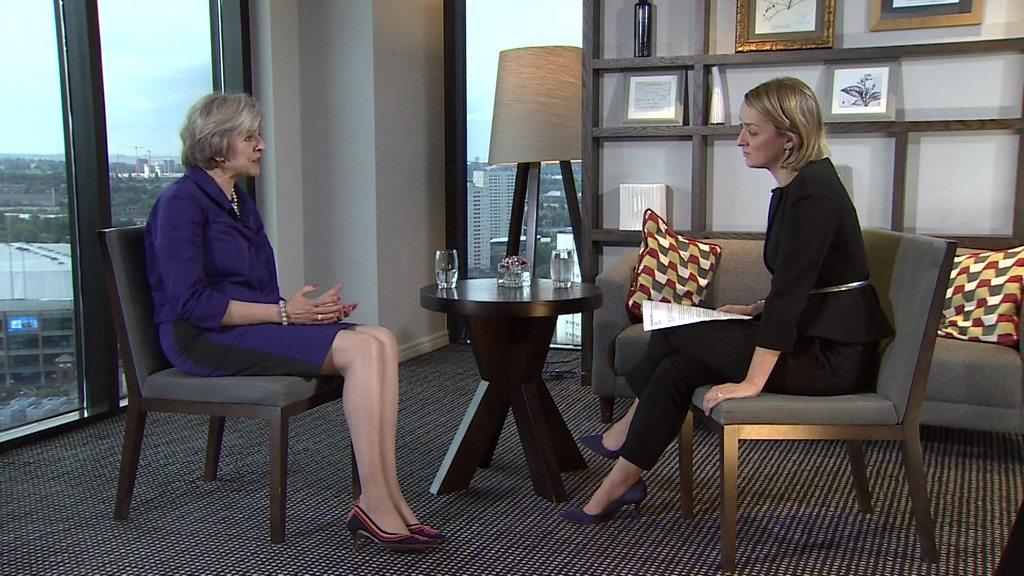

Theresa May and the charismatic clowns

- Published

Smart politicians ride the wave of the times, but the really special ones surf the coming curve, the wave of the future.

For years I have been watching and predicting the rise of those politicos who defy our stultifying times - who throw aside the conventions imposed by the media and their fellows and allow themselves to be themselves, whatever the risks.

Voters have been entranced by authenticity in an age of plastic politicians.

So it is fascinating that Theresa May bucks this trend for blokeish charm. Is she just an anomaly bucking the trend or does it tell us something more profound?

Of course, like anything else, political personas go in fashions and cycles.

After a parade of politicians who seemed from a different era to the majority of their voters, those such as Bill Clinton, Tony Blair, Gerhard Schroder, external and David Cameron deliberately struck a fresher note.

For many, Bill Clinton's political legacy was ultimately tarnished by his personal conduct

They played guitars and played along with popular culture. They were fathers, with families, with children.

But these masters of spin were also mastered by it - never a hair out of place, never a word not carefully chosen.

Well, Bill was always different, shall we say, the first of the "unbuttoned".

A personal grievous flaw? Or something that unwittingly highlighted the fact that some people could break all the rules and get away with it?

Nigel Farage, Boris Johnson and of course Donald Trump do things differently.

They all have a very personal style, grounded in a frankness that deliberately courts the accusation of offensiveness - funny to some, not to others - themselves, authentic.

They are willing to galumph through minefields regardless of the big bangs going off all around them.

But now the chain of explosion has completely altered the landscape, has the mood charged towards such casual disregard for the impact of words?

Boris Johnson projects an unkempt, humorous persona rarely seen in modern public life

For Theresa May is the antithesis of the these charismatic, chaotic, clowns.

Guarded, buttoned up, almost inscrutably private - no so-called "sofa government", and no chance of allowing emotional insights to spill over and stain the upholstery. She is upright and controlled behind her desk.

She is the most private person to become prime minister for years.

Her father died following a car accident when she was in her 20s, and her mother, who had multiple sclerosis, not long afterwards.

Asked recently about the impact of this loss, she paused and suggested, all of a rush, that it had impelled her towards success in public service.

Theresa May, pictured on holiday with her husband Philip, has guarded her personal life

If this was a true reflection of her feelings, she would be a psychopath. She is not - but she is unwilling to share her most private feelings with the rest of us just because she is running the country.

It is a personal instinct. But it is also a political tactic, and a very successful one.

She is the leader of our country precisely because of her sphinx-like opacity. During the referendum she was a lukewarm loyalist, her opinions modestly draped in seven veils when others were exotically dancing around leaving nothing to the imagination - Mrs May-be, maybe not.

This has allowed her considerable room for manoeuvre. She has backed the choice of 52% the British people - a choice she apparently thought was unwise a few short weeks ago - with enthusiasm. It is not brave, it is not bold, but it is the way to bring her party behind her.

But more importantly, as Andrew Rawnsley first pointed out, external - and as the prime minister set out explicitly in her conference speech - she understands that Brexit does not just mean Brexit. It points towards a whole swamp of discontent.

She is moving to occupy UKIP's territory, waterlogged old Labour ground, drain it and reclaim it for the centre.

But she is doing it in her own way.

Observers see parallels between Theresa May (left) and Angela Merkel

She may buck the trend of the open spirits, who are always ready with a glib quip, but she is not without compatriots.

Hillary Clinton and Angela Merkel are also people who weigh the balance, check their language and try not to talk about themselves.

They also happen to be women, which may or may not be a coincidence.

I am, in general, wary of drawing too many conclusions from these observations.

It is a pitfall of the job to want to tie everything up with a thesis or theory, either out of a desire for neatness, or just a pithy paragraph.

I will let you know when I have one - but for the moment, I just observe Mrs May is a politician who strives against the mood of the times.

The danger for her is that the less that is on show, the more people want to get under the surface.

And this Sphinx will in the end have to answer her own riddle - what does Brexit mean?

Mark Mardell presents The World This Weekend on BBC Radio 4 on Sundays at 13:00 or you can listen online.

- Published25 July 2016

- Published4 October 2016

- Published14 July 2016