Where did it all go wrong for UKIP?

- Published

The fracas between two UKIP members of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, which ended up with one of them being hospitalised, is the latest in a series of PR disasters for the party,

It follows the resignation of its leader Diane James after only 18 days in post, public rows over how the party is run, and a bitter battle over its leadership in Wales.

How did a party which won nearly 4 million voters at the last election and triumphed in the EU referendum get into such an apparent mess and where does it go from here?

How and when did the turmoil start?

Things were going so well for the party in 2014

The bad blood which is currently being spilt in the party can largely be traced back to the 2015 general election and its aftermath.

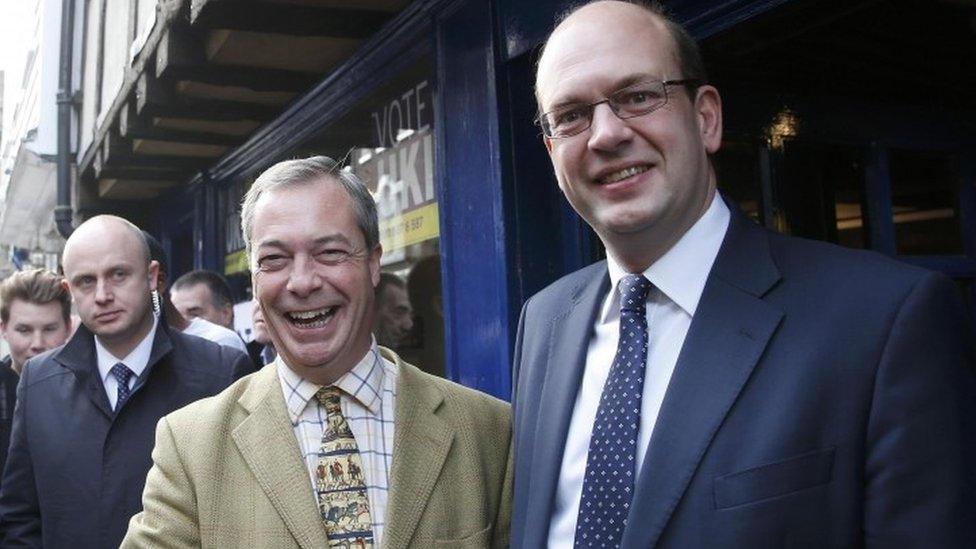

It was all very different back in the winter of 2014. At that point, the party was carrying all before it, having topped the polls in the European elections and persuaded two Conservative MPs - Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless - to cross the floor and join it.

All the talk was of further defections from Conservative ranks and UKIP winning up to a dozen seats in the following year's election.

Of course, none of this happened. UKIP surpassed expectations by getting nearly 4 million votes and 12.6% of the vote - an extraordinary performance by any measure.

But that only translated into one parliamentary seat while leader Nigel Farage, who had bestrode the party like a colossus for a decade, suffered personal disappointment by failing to get elected in Kent.

Farage's unresignation

Nigel Farage has resigned before but this time he says he is going once and for all

Mr Farage had vowed - many say unwisely - to stand aside if he wasn't elected to Parliament and he duly did so, naming rising star Suzanne Evans as his preferred interim successor.

But the party's ruling national executive committee refused to accept his resignation - arguing he had a key role to play in the forthcoming EU referendum - and within days his "un-resignation" was official.

This was a pivotal moment, with some grateful for the U-turn, others believing it tarnished Mr Farage's credibility and made the party look like a personality cult.

What followed were weeks of briefing, counter-briefing and manoeuvring, in many ways a less vicious precursor of the current strife.

The wounds that were inflicted during this period of conflict have never really healed, despite the party seeing its dream ambition - the UK voting to leave the European Union - realised.

This summer's at-times farcical leadership contest and the events in Strasbourg involving Steven Woolfe and Mike Hookem all indicate a party that is going through something of an identity crisis.

Is it all down to personalities?

Diane James was portrayed as a unifying figure but only lasted 18 days

Not entirely, but in this case it is wrong to pretend the schisms in the party are solely or even fundamentally about politics or the party's future direction.

Like a medieval court, personalities matter and the succession is the one issue that, above all, preoccupies the party.

This is a reflection of the success of Nigel Farage and the almost impossible task - like those who followed Sir Alex Ferguson at Old Trafford - that anyone hoping to take over from him faces.

Under his leadership, the party has advanced from the fringes of British politics - when it was derided by opponents as being full of "fruitcakes and loons" - to the mainstream, setting the agenda on many issues and seeing its policies adopted by other parties.

In her resignation letter, Diane James suggested there were some in the party unwilling to accept her authority and move on and it is unclear whether whoever follows her will fare any better.

Two tribes go to war

Senior figures have argued openly about UKIP's future

Although one has to be careful not to generalise, there are, broadly speaking, two factions in the party and the animosity between them is real.

One group is aligned around Nigel Farage, many of whose members would ideally prefer him to continue as leader but, knowing that he wants out, are focused on ensuring his successor is cut from broadly the same cloth and will pursue the same leadership style.

They grouped around Steven Woolfe this summer and, when he was barred from standing after submitting his paperwork late, transferred their allegiance to Diane James.

Among the most vocal members of this group are the party's main financial backer Arron Banks, Raheem Kassam - Mr Farage's former chief-of-staff who is now standing to be leader - and the party's former leader in Wales Nathan Gill.

On the other side of the trenches are those who, while respecting Mr Farage's achievements, believe he has taken the party as far as he can and feel it is time for a more collegiate approach and more inclusive, less polarising message. In this camp, you will find Suzanne Evans, Douglas Carswell and former director of communications Patrick O'Flynn.

They rallied round councillor Lisa Duffy in this summer's campaign but found themselves comprehensively outgunned by the other wing of the party - with James winning 46% of the vote.

Many UKIP-watchers believe the original contest should have been between Steven Woolfe and Suzanne Evans - who was suspended at the time - and this is what will play out this time around - assuming Mr Woolfe decides to continue after the trauma of recent days.

Not all the party's 22 MEPs fit snugly into either of the two groups and there are some key figures - such as former deputy leader Paul Nuttall or new Welsh leader Neil Hamilton - who have their own power bases and - some would argue - axes to grind.

Don't policies matter in all this?

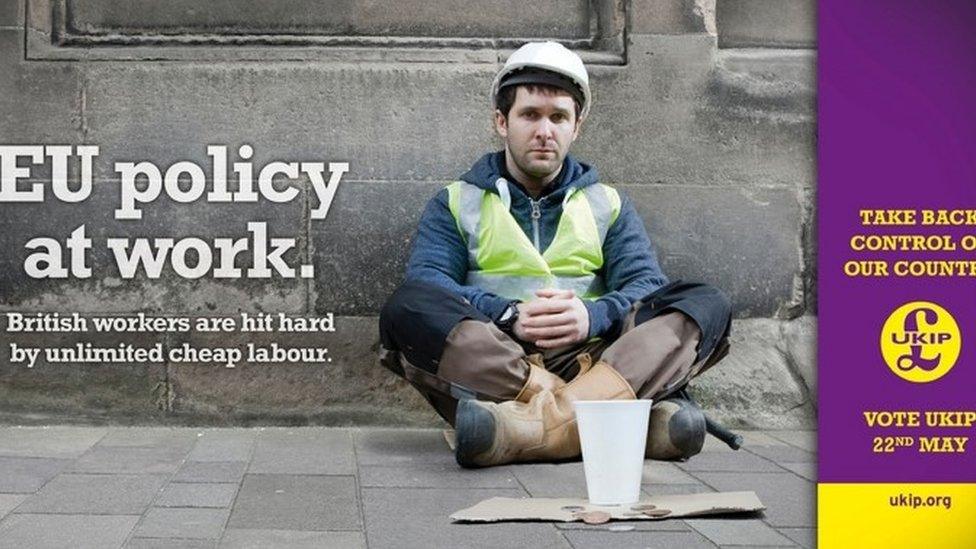

UKIP has been using concerns about immigration to target skilled workers in Labour areas

As is often the case with parties supposedly at war with each other, UKIP actually agree on an awful lot - leaving the EU as soon as possible, ending freedom of movement rules, slashing foreign aid, expanding selective education, less military intervention abroad and so on...

There is broad agreement that the party needs to become more professional, more disciplined and overhaul the way it makes decisions - including scrapping the NEC to reduce the power of voluntary members.

There is also consensus, in the post-referendum age and with David Cameron gone, that UKIP's electoral future - aside from a few Tory-held seats in the east of England - lies in going after "soft" Labour territory in parts of the Midlands, Yorkshire and the north-east of England.

These are all areas where UKIP did well last year, where there was a large Leave vote in the referendum and where, so the conventional wisdom goes, people are not warming to Jeremy Corbyn and his more liberal message on immigration and other issues.

While its long-term ambition is not in doubt - becoming the official opposition in England - it is how it gets there and the tone it adopts in doing so which really divides those vying to shape its future.

Five-star future?

Is Donald Trump's campaign a pointer to UKIP's future?

UKIP has come a long way in 20 years and it would be easy to dismiss its current problems as growing pains - were they not clearly more serious than that.

The party got where it is by cultivating a mixture of populism, nationalism and euroscepticism - with disdain for the global establishment and an outsider, underdog status thrown in for good measure.

It has mopped up protest votes in the past five years but, as the Lib Dems know to their cost, an insurgent party cannot take anything beyond its core vote for granted.

It is an open question how UKIP reacts to Theresa May's leadership and her apparent intention to colonise its ground on issues like immigration but also to appeal to Labour voters on the economy and public services.

Should UKIP try to outflank the Tories in working class seats in the north of England - where they are still treated with suspicion by many - or persist with a more traditional conservative, low-tax, small-state message?

Should it be copying the so-called post-ideological approach of the Five Star Movement in Italy - something Nigel Farage is reported to be keen on - or ape the blue-collar, culture war approach that has underpinned Donald Trump's unconventional tilt at the White House?

While the UK is still a member of the EU and the risk of a "soft Brexit" remains, UKIP has a single, over-arching issue that it can unite around.

If and when that is no longer the case, the party's ideological moorings may seem less secure and the search for a new purpose and direction is clearly at the heart of the current tribulations.

- Published7 October 2016

- Published4 November 2016