What did the Brexit vote reveal about the UK?

- Published

The vote for Brexit was a thunderous rumble of national indignation, an outpouring of frustrated fury that shook the foundations of the British state. We misinterpret its meaning at our peril.

"Brexit means Brexit" does not cut it.

This was much more than a simple referendum about membership of the European Union. Neither Brussels bureaucrats nor Polish plumbers were really the motivation for a popular revolt unparalleled in almost five centuries.

This was an act of extraordinary defiance against a system that does not and will not listen to people's concerns and anxieties.

We need to be honest. Our governance, our democracy, does not function properly. It is failing the people of this country. That is the message of Brexit.

The reason the referendum result caught pundits and pollsters so totally by surprise is that they were applying the outdated rules of our 20th century politics to a 21st century question.

Westminster power is constructed around an ideological divide forged in the furnaces of the industrial revolution. Our politics is still routinely discussed in terms of left and right, workers and bosses, socialism and capitalism.

But look at the Brexit vote and you realise these historic distinctions simply did not apply in the referendum. The working class tended to vote Leave and yet most Labour supporters voted Remain. The professional middle-class tended to vote Remain but most Conservatives voted Leave.

The rich Tory shires and the poor post-industrial Labour heartlands found common cause. They both voted to leave.

I was very struck by the attitude of people I met in Port Talbot in South Wales.

Mark Easton reports from Port Talbot

Here was a place that has in the last decade received around a billion pounds in EU aid. It was due to receive around a billion pounds more over the next few years - money that is now very much in doubt.

And yet they voted emphatically to leave. Port Talbot is virtually untouched by the waves of immigration that some suggest was the driving force behind the referendum vote. I did not detect any profound ideological concerns over UK sovereignty either.

What I did hear were people who did not think anyone was listening to them. They felt powerless and ignored.

It is understandable. Everything in Port Talbot depends on the steelworks and its future is decided by people whose names they do not know in a boardroom in Mumbai. Globalisation has robbed the people of this proud Welsh town of their voice and they are far from alone.

There was a time when people up and down the land believed they had some kind of control over their destiny. But one by one those traditional connections to power have been snapped.

Trade unionism has been neutered, local government is a shadow of its former self and political activism is, for the most part, simply shouting into the wind.

National elections are all but meaningless in Port Talbot, a town that has consistently returned a Labour MP since 1922. Across Britain, there are said to be fewer marginal seats than at any time since 1945 and many more very safe ones, including Aberavon in south Wales.

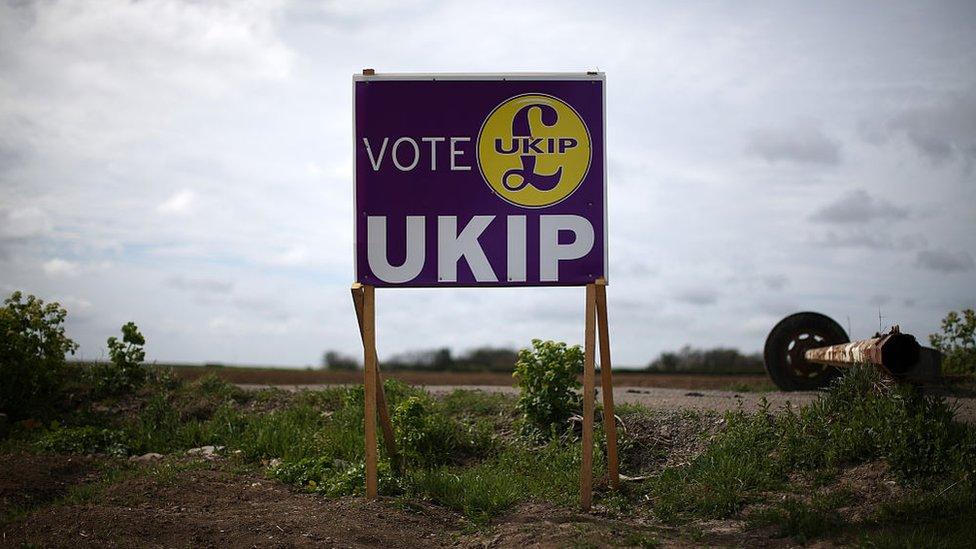

One person in eight voted UKIP at the 2015 general election - 3.8m people - but the party has only one MP, Douglas Carswell.

Our first-past-the-post system entrenches traditional power structures, incubating resentment among millions of electors who know, rightly, that in general elections their votes and their voices are of no consequence.

That sense of a system disconnected from ordinary people is just as evident in the towns and villages of rural England, places which also voted emphatically to leave the EU.

In the true blue Cotswolds, I met a Conservative Party member who despaired that, in his own words, two whole aisles in his local Tesco had been given over to Polish food.

He was not a racist, nor even a xenophobe, but he was frustrated that cultural change had come to his neighbourhood without notice or consultation.

Decisions made in Westminster and Brussels resonate down to the supermarket shelves of Gloucestershire and local people do not feel they have had any say in the matter.

The Brexit campaign was centred on the idea of taking back control. That is what it said in huge letters on the red bus - a slogan that went far beyond the demand for control of our borders.

The point was that people all over Britain were desperate for a democratic system that gave them some semblance of control over their destiny, in a globalised and interconnected world where decisions often seem to be made by anonymous elites a long way away.

To them, the European Union was one obvious villain.

It conjures up a mental picture of mirrored glass and chrome, black limos with tinted windows and unfamiliar faces speaking in foreign accents after meetings behind closed doors.

It gives no impression of listening.

The "metropolitan Westminster elite" was another. Britain has one of the most centralised governments in the developed world.

Only 5% of tax revenue is raised locally in the UK - by far the lowest figure in the G7 - and much of what local politicians do is dictated by the powers in Westminster under statute.

The complaint of many is that national politicians are not listening either.

Shortly after the referendum, the then Local Government Secretary Greg Clark told English council leaders: "When we are transferring powers from the EU to Britain, I think it is essential that Whitehall is not the default destination for them.

"Among the answers to the challenge that the referendum result poses has to be a much bigger role for the local in our national life."

And he is surely right. Brexit was a cry of pain from a country that no longer believes that traditional democracy offers the answer.

Prime Minister Theresa May also referred to the political disconnect highlighted by the Brexit vote in her party conference speech: "It was about a sense - deep, profound and let's face it often justified - that many people have today that the world works well for a privileged few, but not for them."

"We need them to know that they have a voice that will be listened to," Mrs May went on. "In our democracy no citizen will ever be rendered voiceless or powerless by a mighty state or a mighty bureaucracy."

That is the challenge of Brexit - how to give people their voice.

But, of course, making that happen will require profound courage and imagination from our national political leaders because it necessarily means they give up some of their own power.

They are sustained by and steeped in traditional national party politics, an old-fashioned left-right approach to the world that does not reflect the Brexit vote or the subtle views of most voters.

What the British people want, I believe, is a democracy honest enough to reveal the trade-offs and the complexities of contemporary politics, responsive enough to reflect nuanced opinions, and convincing enough that people believe they are genuinely connected to the decisions that affect their lives.

When we cut our ties with EU power, we must also reform Britain's archaic power structures.

That is surely what Brexit must mean.

- Published21 December 2016

- Published20 December 2016

- Published28 March 2017

- Published30 December 2020