Brexit: The mind games

- Published

Psychology is always part of tense negotiations. In her Lancaster House speech this week Theresa May sought to seize back the advantage before the real battles start at the end of March. She wanted Europe to know that Britain would not be coming to meetings on the defensive, cap in hand.

During the 40 minutes of her speech she managed to shift the balance of power a little. A few days before she spoke I had been in Brussels and had spoken to a very senior European figure.

He was pessimistic. Mrs May, in his view, did not have a good relationship with other European leaders. He thought the negotiations could "go wrong from the start" and was in no doubt that in those circumstances the UK would be the loser.

He pointed out that Brexit was not high on the agenda for voters in the other 27 EU states. It was a way of saying that in the forthcoming negotiations the UK was the needy one. Britain would have to compromise.

What he reflected is the widely-held view in the EU that the divorce will be messy, that real damage will be done to the British economy.

Mrs May chose to exude confidence. The UK was determined to become a "champion of world trade" and was unafraid of negotiations turning difficult. The message was delivered with clarity and was intended to shape the mindset of those with whom Britain would be negotiating.

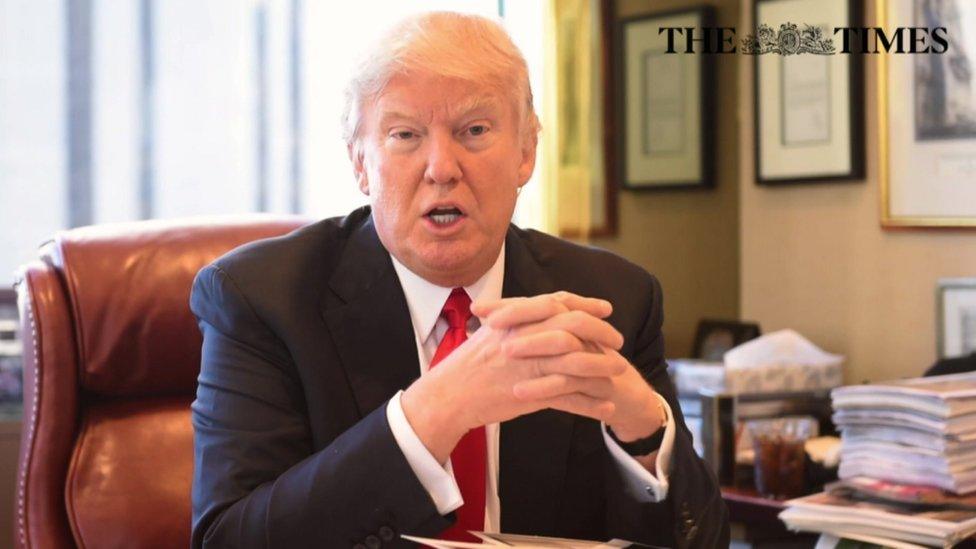

Donald Trump has intimated that he wants a fast-track trade deal with the UK

Two factors had strengthened Mrs May's hand. Firstly, the intervention of Donald Trump. The president-elect declared he was willing to fast-track a trade deal with the UK. There was no more talk about Britain being consigned to the back of the queue.

Secondly, and most importantly, the British economy has performed much better than was predicted. Consumer confidence has remained high and crucially the economy has bought Mrs May some political space and strengthened her hand.

Her speech was conciliatory in part. She made it clear she wanted the EU to succeed and did not seek the unravelling of the European Union and wanted Britain to "remain a good friend".

That was an important gesture because it is quite clear that some of those who backed Brexit would relish the break-up of the EU. And her stance was in marked contrast to that of Mr Trump who predicted last weekend that "others would leave" and that it would be difficult to keep the EU together. One EU ambassador to the UK said it sounded like Nigel Farage had briefed Mr Trump.

What Mr Trump has done is to encourage European leaders to circle the wagons by accusing Angela Merkel of making a "catastrophic mistake" with her welcoming of refugees, so chipping away at her authority. Mrs May, in contrast, was offering to be a good neighbour.

But, much as she offered friendship, there was no disguising the fist inside the gloved hand. If there was any attempt to punish the UK for breaking away it would do "calamitous self-harm" she said and "would not be the act of a friend".

Slovakia's Prime Minister Robert Fico has warned against an agreement that would strengthen the UK at the expense of the EU

Britain, if necessary, would go it alone. "No deal would be better than a bad deal." It was an attempt to seize the psychological advantage in the talks, by reducing the threat of them failing.

She was clear that the UK was leaving the single market but sought a "bold and ambitious free trade agreement". If that was denied and high tariffs were introduced then Europe's leaders would have to answer to their voters.

"I do not believe," she said, "that the EU's leaders will seriously tell German exporters, French farmers, Spanish fishermen… that they want to make them poorer, just to punish Britain and make a political point."

That was a way of saying that if the talks turned ugly then all sides would suffer damage but that Britain would not flinch from telling European voters that their leaders were putting ideology above economic self-interest.

This is an important undercurrent to the negotiations. I have never seen Europe's leaders so unsure and anxious about the future of the European project. They genuinely fear that if another country was to leave it would mark the end of the EU. That is what underpins the unity they have shown so far.

It is also why they insist that Britain must not be able to walk away with a deal that was better than they would have got by staying on the inside. Slovakia's Prime Minister Robert Fico said it would not be "right for the 27 remaining EU countries to emerge weakened and Britain strengthened".

So, in its negotiating strategy, the UK has to talk up the mutual economic benefits of compromise.

Regarding the City of London, the message is that there is a mutual interest in its continued health. Here again, the UK is arguing that the EU needs access to pools of capital and it needs the financial skills that only the City offers.

Protecting the pre-eminence of the City will be central to the UK's Brexit aims

The UK also wanted to leave a threat on the table: that if a deal could not be done the UK would take any measure to protect its economy, including turning it into a low tax area on the edge of mainland Europe.

May wanted to give her European audience some incentives. Firstly, that Europe needs the UK economy but also that it needed Britain's intelligence services and armed forces.

She was not offering security as a bargaining chip but she knew her pitch would resonate in parts of Eastern Europe and the Baltic States where they have grown uncertain of the Nato umbrella and are grateful for the sight of British forces on training exercises.

These are all strings that can be pulled as negotiations unfold over the next two years.

For all the strategy that lay behind Mrs May's speech, the headline that resonated around Europe was that Britain was leaving the single market. Some European papers accused Britain of turning inwards and of being "Little Britain".

The UK can live with those opinions but its position over the customs union is far more problematic. The UK wants to leave the customs union because it wants the freedom to negotiate trade deals with other countries. At the same time it wants to avoid tariffs and trade barriers.

The prime minister has spoken of negotiating associate membership of the customs union with special access for certain sectors like car manufacturing. This will be a tough part of the negotiations. To other EU states it looks like the cherry-picking they have vowed to resist.

Securing a trade agreement will take time and, almost certainly, some transitional arrangement. Mrs May, however, insists a trade deal can be negotiated within two years. That is hugely ambitious but she fears a transition would involve continuing to pay into the EU budget and accepting EU rules and that would be rejected by elements within her party.

Failure, however, conjures up the danger of the UK going over the cliff edge without a deal. That is a powerful card for the other EU countries and for MEPs in the European parliament who will have to vote on all this.

The dilemma for the 27 EU members is this: they believe it is necessary to demonstrate that leaving the EU is painful and risky. The UK must be seen to suffer, but the question is whether they can do that without hurting themselves.

What Mrs May did was to remind Europe that it does not hold all the cards. This was round one in the psychology of doing a deal.

Many European leaders did not like the message and warned that "Britain can't dictate the terms of separation", with the President of the Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, saying it would be like negotiating not with an EU member but with a '"third country".

- Published17 January 2017

- Published30 December 2020

- Published16 January 2017

- Published27 June 2016