General election 2017: How much do the parties know about you?

- Published

From the campaign leaflet pushed through your letterbox, to the party message on social media, election material is increasingly targeted at individual voters. So, just how much do political parties know about you?

You can expect to receive a lot of communications from political parties in the coming weeks, as they prepare for June's election.

It's the same for everyone on your street, a place full of different characters - some with children, some younger, some older.

There is likely to be just as much political difference among your neighbours, from the loyal party supporters to those changing their vote at each election.

In other words, whether your constituency is described as a "middle class suburban seat", a "traditional working class community", or a "Remain voting area", there are still significant differences between individual voters.

The election leaflets you receive may depend on what the parties know about you

This matters a great deal to the parties and it's highly likely that friends and neighbours will receive very different campaign messages from the parties - even different ones from the same party.

Winning over the waverers

For several elections now, parties have been making use of many different sources of data to target information at voters.

This use of big data has become very important to them for three key reasons.

First, we voters have changed quite a bit. In fact, we've been changing quite a bit for the last 40 years.

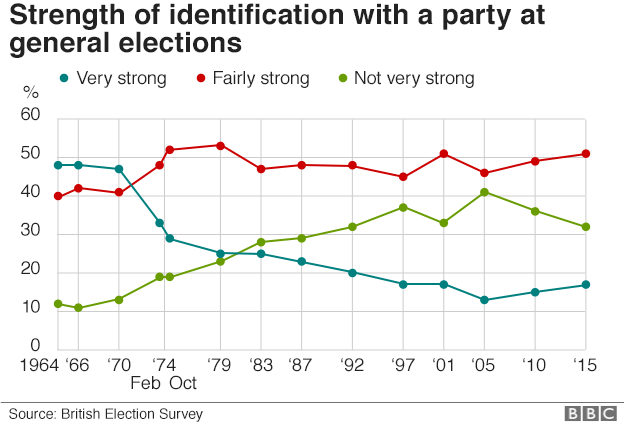

Traditional allegiances between voters and parties have declined rapidly and while there are still strong party loyalists, there are far fewer than there used to be.

This means more voters are unsure as to how they'll cast their vote - a big opportunity for the parties, because winning the backing of these voters means they will not just be relying on their core support.

As a consequence, parties have been targeting seats much more intently and with greater precision.

The second reason is that while membership of many political parties has risen in recent years, they have generally had fewer volunteers that they can call on come election time.

This means that technological developments such as using data to target voters have provided a useful alternative.

Thirdly, parties have become more efficient.

There is little point in seeking to convert voters who are committed to another party, or indeed strong supporters already on your side.

Instead, parties are increasingly focused on the "waverers" and "undecideds" - the people whose votes are going to win elections.

Finding 'Essex Man'

To do this, the parties go to great lengths to combine a whole range of data sources.

First, they use their own canvass returns - information about voting intentions - collected on the doorstep and the telephone over the course of a few years.

The most recent information collected from voters is now uploaded in real time.

This tells the parties if the would-be voter is a committed supporter, "waverer" or "undecided".

They then combine this with market research data, which tells them more about the individual - demographic characteristics such as age, sex, education level, income and family size.

This is the information which has led parties to create key target groups at past elections - so-called "Essex Man" or "school gate mums", for example.

In turn, these are then combined with further information the parties have gathered on the doorstep, from telephone calls and social media engagement.

Tailored leaflets and other messages reflecting the voter's interests and concerns can soon follow.

So, while a family with young children might receive a leaflet about what has been done for primary schools in the area, their retired neighbour may receive a different circular about what is being done to help pensioners.

Facebook is increasingly important, offering the possibility of sending targeted messages to certain groups of voters and different messages to those with other concerns.

The human touch

So does it make any difference? The short answer is yes.

This use of big data to target key voters and decide where to focus resources invariably leads to stronger electoral performances.

This was well illustrated at the last general election, where all three of the main parties improved their performance as a result of their targeting strategies.

All three parties ran their most intensive campaigns in the seats that mattered most.

Indeed, had Labour and the Liberal Democrats not targeted voters so well, their results would have been even worse.

Yet for all that, big data alone will not win elections.

Over the last six elections, the one approach that works better than all others when persuading voters is face-to-face contact.

Face-to-face contact - still the best way to connect with voters

So, while the use of big data matters - and makes election messages more personal - it plays a supporting role to human contact, rather than replacing it.

All of which makes this election a particularly interesting one.

Campaign techniques which focus on big data usually begin long before polling day - maybe six or nine months before.

But this snap election doesn't afford that luxury and there is a danger in bombarding voters with the same volume of communications in four weeks.

So ironically, this election may prove to be more traditional - still informed by big data, but with a stronger focus on the human touch.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Justin Fisher is professor of political science, external at Brunel University London. Follow him @justin_t_fisher, external.

His research on election campaigning has been funded by the Economic and Social Research Council, external.