Reality Check: What do we know about 100bn euro Brexit bill?

- Published

Calculating a final bill for the UK is likely to be the focus of a huge political row

An estimate of the likely "divorce bill" for the UK to leave the EU has risen sharply from 60bn euro to 100bn euro (£50.7bn-£84.5bn), according to a report in the Financial Times on Wednesday.

But how has this figure come about? What will the money be used for? And what happens if the UK decides not to pay? BBC Reality Check correspondent Chris Morris answers your questions on the EU Brexit bill.

Where does the 100bn euro estimate come from?

The figure is just one of the many estimates - the highest so far - of the amount that the UK might have to pay when it leaves the EU.

As yet, there are no official figures coming from either Brussels or the UK, although senior EU politicians have spoken publicly of a figure of about 60bn euro.

Calculating a final total will involve detailed technical and legal negotiations. It is also likely to be the focus of a huge political row.

The EU's draft negotiating directives, released on Wednesday, speak of a single financial settlement that "should be based on the principle that the United Kingdom must honour its share of the financing of all the obligations undertaken while it was a member of the Union".

Will the financial settlement be itemised?

The EU directives do begin to itemise what that means.

The financial obligations, they say, should include the EU budget, the termination of UK membership of EU institutions such as the European Investment Bank and the European Central Bank, and the participation of the UK in specific funds and facilities related to union policies such as the European Development Fund and the Facility for Refugees in Turkey.

Michel Barnier said Britain's financial obligations to the EU were "indisputable"

Releasing the draft directives, the EU's chief negotiator, Michel Barnier, said: "We are going to enter into rigorous and objective work, which in my mind must be indisputable."

But there will be disputes over how much of all of this the UK is actually liable for.

Dispute number one will be about how you calculate the overall total. If anything, the attitude of EU member states like Germany and France has hardened over recent weeks.

Initially the European Commission recommended that the UK's share of EU assets should be subtracted from a final bill, but that is no longer the case.

EU officials say this is because assets are owned by the EU as an entity, rather than by the individual member states.

Dispute number two will be about what the UK share of the overall total should be. It could be about 12% (which is the average UK contribution to the EU budget over the last few years) but it could conceivably be as high as 15% based on the size of the UK's gross national income.

What is a reasonable price to leave?

It's impossible to say what that would be - it depends on your perspective. If compromise can be achieved, and if payment is spread over many years, the amounts involved may not be significant economically. But politically this debate will be dynamite.

Why are we still paying?

We are still paying because we are legally part of the EU until the end of the Article 50 negotiations - ie until 29 March 2019 (unless all EU countries agree they want more time to negotiate).

As long as we are a member, we pay into the EU budget and that money is then used to pay for all sorts of projects, from infrastructure to art and conservation across the EU - including in the UK.

If both parties agree on a transition phase to ease the passage from full membership to a new relationship in the future, some form of budget payments will continue after Brexit.

Even after a transition is completed, we may well choose to pay money into the EU budget to take part in specific EU schemes, such as student exchanges and research projects.

What if we pay nothing? Is there a legal requirement to pay?

If we stopped paying at the moment, we would be breaking the law. So yes, there is a legal requirement.

In the event of negotiations falling apart and no deal being done, we could - according to a House of Lords committee report - walk away without paying anything.

But that would lead to legal disputes that could eventually end up in the International Court of Justice in The Hague. A legal case at the ICJ would be a messy and undesirable outcome for almost everyone.

What will the money be used for by the EU?

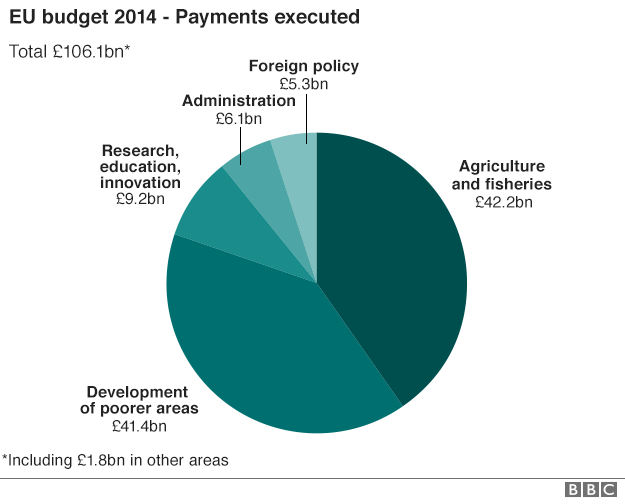

The EU will use the money for all its continuing projects. Here are the main current areas of EU spending.

Click here for more detail of what falls into each category.

The EU spending priorities might change when the bloc agrees a new long-term budget which will run from 2021 for seven years.

What will the EU lose when the UK leaves?

The EU will lose around 12% of the total that is paid every year into its budget. The figure is the average that the UK has paid over the past five years. But it will save some money too, because it would no longer pay for farmers or for other projects in the UK.

On average, the UK pays around 10bn euro a year net into the EU budget. That is the amount that the EU will have to find elsewhere after Brexit. Alternatively, it will have to cut such an amount from its future spending plans.

Will it cost us more to leave or stay?

This will depend on the economy as a whole. The UK's EU budget contribution is very small compared with the amount of money at stake in sorting out a future trade relationship. So getting a good trade deal with the EU in the future is more important for the health of the UK economy than the size of the divorce settlement.

In trying to analyse the cost, you also have to take account of timescale. In the short term, leaving could be much costlier than staying. But in the long run it will depend on how well the economy as a whole performs.

Will there be an impact on UK trade deals with non-EU states?

The negotiations about a financial settlement will have no impact on UK trade deals outside the EU. But Brexit itself will have a significant impact on such agreements.

At the moment the UK does international trade deals as part of the EU - it is EU officials that negotiate them on our behalf.

After Brexit, we will have to agree upon a new trading relationship with the remaining 27 EU countries. And we will have to negotiate our own separate trade deals with other countries around the world.

The government hopes that the UK acting alone will more nimble, and more able to finalise deals quickly. Its critics say the UK will have less influence when it is no longer negotiating as part of a larger trading bloc.

- Published3 May 2017

- Published1 June 2017