Reality Check: What does nationalising the railways mean?

- Published

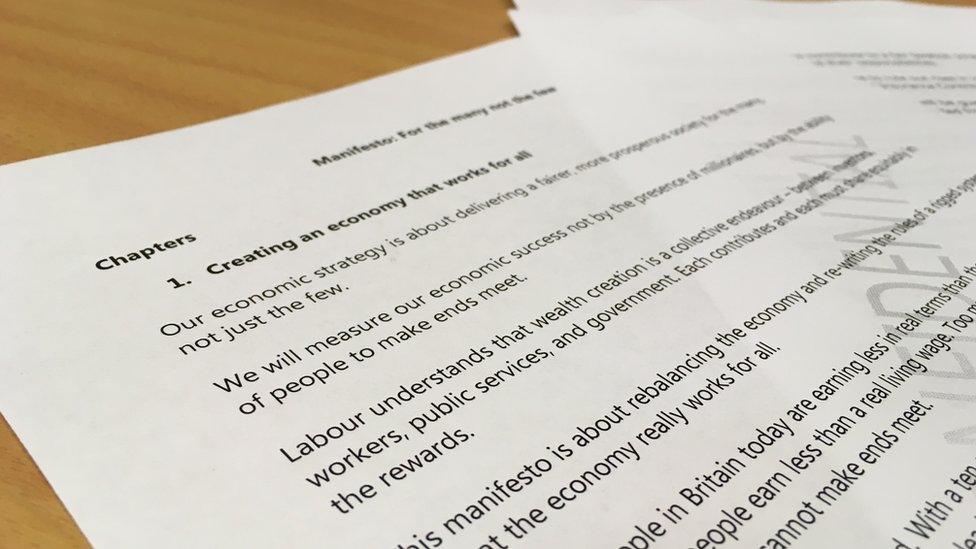

A draft of Labour's leaked election manifesto pledges to bring Britain's railways back into public ownership. Reality Check has been looking at how this renationalisation might work.

Britain's rail network was first nationalised by Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee in 1948 and then privatised again under Sir John Major's Conservatives in 1993. Now, 24 years on, Labour says our railways have become inefficient and expensive; it wants to see a return to public ownership.

Labour's pledge appears to resonate with the public. Two years ago, a YouGov poll suggested half of voters would prefer trains to be run by the public sector, while one in four favoured private ownership.

Since privatisation, the number of passenger journeys have increased from 735 million in 1994-95 to 1.7 billion in 2015-16, according to the Office of Rail and Road.

Passenger Focus says that in 2016 customer satisfaction was 81%, down from 83% the previous year.

So how would nationalisation work?

Under the existing system, Britain's railway lines are run by train operating companies as franchises for a fixed length of time.

There are currently 18 franchises in England, Scotland and Wales.

With the odd exception, the shortest contracts run for seven years, although 10 years is more common.

Northern Ireland's rail system has remained nationalised since 1948.

The train operating companies are not responsible for track maintenance, this falls to Network Rail, which is publicly owned.

The government also pays subsidies to the rail industry of more than £3bn a year, of which £0.6bn goes to the franchised train operating companies.

Subsidies might be needed to deliver services in areas that would otherwise not be commercially viable, such as some rural communities.

Maintenance costs for UK railway lines falls to Network Rail, which is publicly owned

According to Sim Harris, managing editor of the industry newspaper, Railnews, the most painless way to achieve renationalisation is to simply let each private franchise run out and phase in public ownership one by one, which is what Labour favours.

However, some contracts still have many years to run; the Caledonian Sleeper franchise, for example, does not expire until 2030.

A faster way of renationalising would be to make companies end their contracts prematurely.

But Mr Harris says this would be problematic as the operating companies would almost certainly challenge the decision in the courts.

This means it could be nearly two decades before full nationalisation could be achieved.

Another consideration is the trains themselves - known as rolling stock.

Rolling stock companies own most of the trains, which they lease to the operating companies.

Labour says it would consider establishing a new public rolling stock company, but this could be expensive as trains would have to be bought back from the private sector or built from scratch.

How does Brexit impact on this?

Brexit should - in theory - make renationalisation much easier.

European Union directives ensure "open access" operations for private companies on all railway lines within the EU.

While that would not mean the government would be prevented from taking over lapsed railway franchises, it does mean the government would not be able to stop a private company from operating their own trains on Britain's railway lines.

Recent public ownership

In 2009, a rare experiment in public ownership was launched after National Express's franchise of the East Coast Main Line collapsed.

A state-run body, called Directly Operated Railways (DOR), was brought in to take over.

In its six years of existence, DOR contributed more than £1bn to the Treasury.

Once that arrangement came to an end, the line was returned to private hands after Intercity Railways - a consortium of Stagecoach and Virgin - promised to invest £140m in the route over eight years, and pay the government £3.3bn for the contract.

Correction 19 May 2017: The £3bn figure referring to government subsidies has been amended to clarify that it covers the whole rail industry.

- Published11 May 2017

- Published11 May 2017

- Published16 August 2016