How the internet helped Labour at the general election

- Published

The 2017 general election was the moment when the internet finally delivered on its long-awaited promise of having a big effect, both on how individual people voted and the overall outcome of the election.

A flood of young voters, many of whom had relatively low levels of political knowledge, used the internet to get news about the general election. This was crucial for boosting support for Labour and Jeremy Corbyn, according to new research on the dynamics of the 2017 vote.

In recent years, there has been talk about the power of the internet to affect elections. Ahead of the 2017 general election, some pointed to a growth of pro-Labour websites and online forums as a potentially powerful weapon in Labour's arsenal.

Our study is one of the first to document how this online activity really did help Jeremy Corbyn and his party.

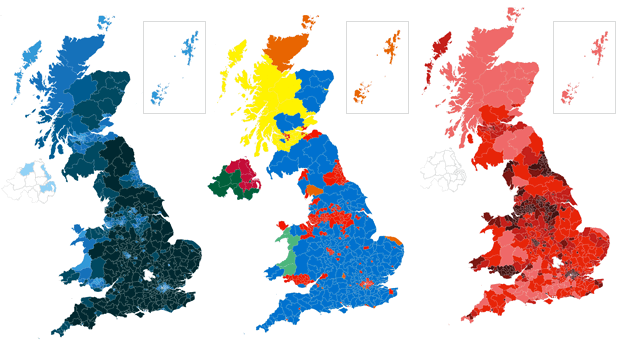

We've found that those who used the internet to get news about the general election were far more likely to have voted Labour. And we observed that those who used the internet less often to gather political news and information were much more likely to vote Conservative.

This relationship is true for the entire electorate and across all age groups.

And it continues to have a strong and positive effect on how people voted, even after we take into account a whole range of factors including age, gender, social class, party identification, how people voted in the referendum and levels of education.

Overall, among all respondents, our research suggests that 16% used the internet "a great deal" to get information about the election, 23% used it "a fair amount", 23% "not very much" and 38% "not at all" or said they did not know.

However, those who use the internet more often were significantly more likely to vote Labour. Sixty-one per cent of those who used the internet "a great deal" to gather news about the general election opted for Labour, compared with only 21% who voted Conservative.

Conversely, 56% who said they used the internet "not at all" voted Conservative, while 30% opted for Labour.

How much people use the internet also correlates with voting patterns among older people. Again, those who said they use the internet a great deal were strongly pro-Labour and pro-Jeremy Corbyn.

The study found that Labour's vote was boosted by young people who followed the election online

These effects involve a combination of two factors: "mobilisation" (things that influence people to turn out and vote) and "persuasion" (things that influence their choice of party). Turnout among people aged 18-29 was up by an estimated 19% on the previous general election in 2015.

Our data shows that both the decision to vote and the choices these young people made at the polls were associated with the volume of news about the election that they consumed online.

Another effect that we find relates to how knowledgeable people are about politics. In our surveys, we tested people's political knowledge by asking if eight randomly selected statements were true or false and then counted the number of correct answers.

The statements included assertions like: "The minimum voting age for UK general elections is now 16 years of age," and "The chancellor of the Exchequer is responsible for setting interest rates in the UK."

Though internet usage and political knowledge are only slightly linked, it is clear that, after rigorous statistical tests, how knowledgeable people are about politics had significant effects on how they voted.

If survey respondents were frequent internet users but did not know much about politics they tended to vote Labour. In contrast, if they weren't internet savvy but knew a fair bit about politics, they tended to vote Conservative.

These effects held across all age groups for both Labour and the Conservatives, with the exception of pensioners in the case of the Tories. This means that those effects weren't caused by the age of the respondent, which at first sight is the obvious explanation for differences in internet usage among the voters.

Put simply, political knowledge continues to have a strong effect on Labour and Conservative voting even after we take statistical account of all of "the usual suspects" that are used to explain voting - such as social class, age, gender income, people's "left-right" placement and how they voted in the 2016 referendum.

The effects of internet usage and political knowledge work strongly through voters' images of the party leaders. Even after we take account of a whole host of other things, like age and income, people with low political knowledge who used the internet to get their election news tended to like Jeremy Corbyn and dislike Theresa May.

Theresa May scored higher than Jeremy Corbyn among those who did not use the internet

For example, among those who said they used the internet "a great deal", the average score for Jeremy Corbyn on a 0 ("really dislike") to 10 ("really like") scale is 6.4, whereas among those who said they did not use the internet at all, his average score is much lower, only 3.4.

The pattern for Theresa May is the opposite: her average score among those who used the internet a great deal is 2.9, whereas among those who did not use the net, her average is considerably higher, at 5.3.

For Jeremy Corbyn, political knowledge, the survey suggests, has a negative effect on feelings about the Labour leader while internet usage has a positive effect. For Theresa May, political knowledge has a positive effect on feelings about the Conservative Party leader while internet usage has a negative effect.

In contrast, people with high political knowledge who did not use the internet for general election news liked Mrs May and disliked Mr Corbyn.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for outside organisations.

Harold Clarke is Ashbel Smith professor at the University of Texas, Dallas. Matthew Goodwin is professor of political science at the University of Kent, Canterbury, Paul Whiteley is a professor of government at the University of Essex and Marianne Stewart is a professor at the University of Texas, Dallas.

Discover more about the methodology they used here, external.

- Published10 June 2017