Brexit: How are the talks really progressing?

- Published

So it's come down to money. Who would have thought it?

After five rounds of negotiations on Brexit, the EU remains insistent: there will be no discussions with the UK on a transition period, or on future relations, until financial commitments have been clarified.

So what exactly is it about the money that is proving so difficult to resolve?

It comes down to the detail (or lack of it) contained in Theresa May's carefully crafted speech in Florence.

Overall, the speech was greeted across the EU with a considerable sense of relief. It suggested that progress was at least possible at a time when some countries were beginning to fear the worst.

The prime minister opened the door for the UK to contribute roughly €20bn (£17.9bn) to the EU budget in 2019 and 2020, so that no-one else would be out of pocket.

And - crucially - she went on to say that "the UK will honour commitments we have made during the period of our membership".

But EU negotiators - under clear instructions from the member states - want to know exactly what that means in practice.

The prime minister said the UK would "honour commitments"

Looming large in the background is something called the Reste à Liquider (RAL) - EU money that has already been committed to projects in the long-term budget but has not yet been spent.

The RAL is currently running at an eye-watering €239bn, which could mean a UK share of more than €30bn.

Much of it is due to be spent on big infrastructure or development projects that have been delayed. There are also pensions and contingent liabilities, such as loans to other countries, to consider.

The EU isn't asking for a figure to be agreed - but for a guarantee within the negotiating process, probably in writing, that "honouring commitments" means "all commitments."

'Time pressure'

The UK position, on the other hand, is that the prime minister made a substantial gesture in her Florence speech, and it is in no position to move further unless it gets something in return.

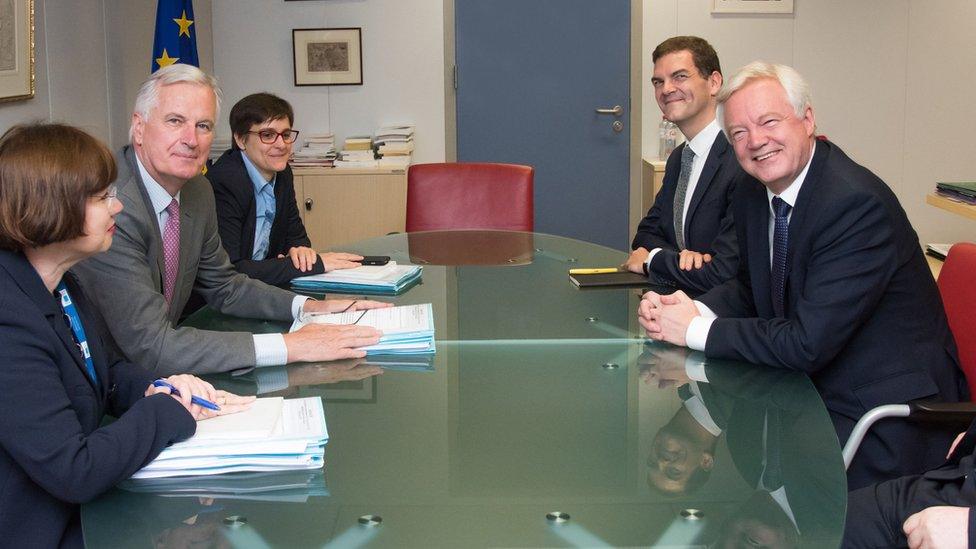

"They are using time pressure to get more money out of us," the Brexit Secretary David Davis told the House of Commons this week. "Bluntly, that is what's going on."

It sounds like deadlock, but that's not necessarily the case. Three more rounds of negotiation have been suggested between this week's summit and another one in December.

The hope is that a way will be found to move forward, even if it takes a moment of crisis to get there.

"The EU27 don't believe the UK is too far off 'sufficient progress'," says Mujtaba Rahman, the managing director for Europe at the political consultancy Eurasia Group.

"They want Mrs May to be able to leave Brussels with a win that will enable her to strike a deal by December."

That's why both sides have said they want to accelerate the negotiating process, and prepare for discussions about the future.

If the language of the current draft of the summit's conclusions doesn't change much, the EU27 will agree to begin internal discussions about a transition period and the nature of a future relationship.

They won't talk directly to the UK about these issues until December at the earliest. And only then if "sufficient progress" has been made on all the "divorce" arrangements, including money.

It doesn't sound like much. But it's a start, and it is seen in Brussels as a carrot for the UK negotiating team.

So what might the EU be likely to decide in internal discussions over the coming weeks?

For EU officials involved in the negotiating process one thing about transition is clear: the more you keep things the same, the easier it will be to agree.

That's why the internal deliberations among the 27 on transition could be concluded very quickly. They will probably offer to prolong all existing EU rules and regulations (the body of law known as 'the acquis') - or, to put it another way - to extend the status quo.

That means that after Brexit - for "about two years" (ie for the length of a transition period) - the UK would be outside the EU's political institutions, but inside its economic arrangements.

It also means the UK would have to accept EU budget payments, EU regulations and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice.

To put it in the formal language of the European Council's Article 50 negotiating guidelines, external: "Should a time-limited prolongation of Union acquis be considered, this would require existing Union regulatory, budgetary, supervisory, judiciary and enforcement instruments and structures to apply."

Difficult to stomach

The details of what that means are difficult for some Brexit supporters in the UK to stomach. But the prime minister, in her Florence speech, has already accepted that the framework for any transition (she prefers to call it an implementation period) would be "the existing structure of EU rules and regulations".

Problems would arise, however, if the UK tried to argue for exemptions or exceptions. Take, for example, one idea that has been floated (forgive the pun): leaving the Common Fisheries Policy at the same time as the UK leaves the EU in March 2019.

That doesn't really tally with the kind of transition that EU officials have in mind. Once you start unpicking the offer, all sorts of complications begin to arise. So it's not quite take it or leave it. But it's not far off.

Unpicking the agreement, such as leaving the Common Fisheries Policy, could lead to further complications

There are other potential problems with a transition period that will need to be resolved. What, for example, does it mean for trade agreements with third countries, when it makes a difference whether products (or parts of products) are manufactured in the single market or not?

But agreeing upon the terms of a transition will be much easier for the EU27 than agreeing on the outline of a final deal - on everything from trade to security. The 27 member states are a little more nervous about those discussions because differences of opinion are bound to emerge between them.

Many countries have obviously been thinking hard about this already. One internal German government paper has been reported here, external.

Finding a compromise

But there is another issue that overshadows debate about Brexit in capitals across the EU - what exactly is it that the UK wants? Every change of emphasis in London adds to the confusion.

As Finland's Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Samuli Virtanen, put it this week: "It seems that at the moment the EU 27 is more unanimous than the UK 1. And that is one of the main problems here."

But it all rests on finding a compromise on money. And that really has to happen before the end of this year. Otherwise time is going to start running out.