Leveson accused ministers of breaking promises to phone hacking victims

- Published

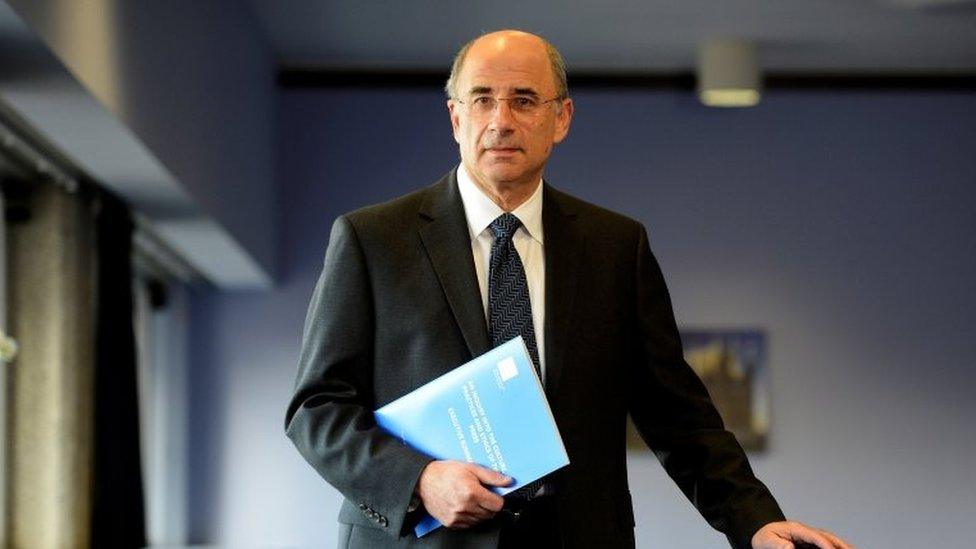

Sir Brian Leveson accused ministers of breaking their promise to phone hacking victims by axing his inquiry into media standards, it has emerged.

Culture Secretary Matt Hancock announced the move earlier, saying the press had cleaned up its act.

He said the changing media landscape meant the second part of the Leveson inquiry was not needed.

But Sir Brian said in a letter to ministers last month he "fundamentally disagreed" with that conclusion.

The judge, who is now head of criminal justice in England and Wales, said the "full truth" about the extent of unlawful behaviour at the UK's tabloid newspapers had yet to be exposed.

And he disputed the government's claim that the press was now sufficiently well-regulated to render further investigation into its culture and practices unnecessary.

'Legitimate expectation'

Part two of the Leveson Inquiry had been due to focus on the relationship between journalists and the police - and Sir Brian said it would have been broadened out to include data protection and "fake news" on social media.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In a letter to Mr Hancock and Home Secretary Amber Rudd on 23 January, he rejected press claims he had no enthusiasm for chairing part two of his inquiry.

He said he would not be available, because of other commitments, but suggested it should continue under another judge.

"I have no doubt that there is still a legitimate expectation on behalf of the public and, in particular, the alleged victims of phone hacking and other unlawful conduct, that there will be a full public examination of the circumstances that allowed that behaviour to develop and clear reassurances that nothing of the same scale could occur again: that is what they were promised," he said.

He added that he did not believe "we are yet even near that position" and urged ministers to consider pressing ahead with the "bulk" of part two "as soon as possible".

'Costly inquiry'

In his statement to MPs, Mr Hancock appeared to play down Sir Brian's objections to the axing of the inquiry.

Matt Hancock told MPs the press was now better regulated

"Sir Brian agrees that the inquiry should not proceed under the current terms of reference but believes that it should continue in an amended form," he said.

"We do not believe that reopening this costly and time consuming public inquiry is the right way forward, so considering all the factors that I have outlined to the House today, I have informed Sir Brian that we are formally closing the inquiry.

"But we will take action to safeguard the lifeblood of our democratic discourse and tackle the challenges that our media face today, not a decade ago."

Mr Hancock told MPs the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO) - set up by the UK's main newspaper groups as an alternative to state-backed regulator Impress - had "largely complied with Leveson's recommendations".

Mr Hancock also announced that the government would not put Section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act - which would force media organisations to pay legal costs of libel cases whether they won or lost - into effect and said they would seek repeal "at the earliest opportunity".

'Huge disappointment'

Labour's deputy leader and media spokesman Tom Watson accused Mr Hancock of being "brazenly misleading" about the public support for going ahead with the inquiry and about Sir Brian's own opposition to the decision to axe it.

"This kind of selective use of facts might not make a tabloid editor blush, but it is not worthy of a secretary of state," Mr Watson said.

Mr Hancock accused Mr Watson of being "tied up with the opponents of press freedom" and said Labour's proposals would "would lead to a press that is fettered and not free".

A spokesman for the lawyers who represented Kate and Gerry McCann, Christopher Jefferies, the Dowler family and other "core participants" at part one of the Leveson inquiry said: "It is astonishing that the government is abandoning it promises to victims of the phone-hacking scandal."

"In 2012, David Cameron made personal promises to the victims of press abuse that the government would implement Leveson. It is a huge disappointment to them that this government has now dropped that completely," said Steven Heffer, of law firm Collyer Bristow.

Ian Murray, executive director of the Society of Editors, welcomed the government's "common-sense approach" but warned that further challenges to press freedom remained in the shape of House of Lords amendments to the Data Protection Bill calling for Leveson part two to be implemented.

But Evan Harris, director of campaign group Hacked Off, said: "If this was any other industry the press would be demanding that inquiry must happen immediately, but when it is about them they applaud the cover-up of a cover up. The government will find it very difficult to maintain this cover-up for long."

What was the Leveson Inquiry?

Lord Justice Leveson was appointed in 2011 to carry out an inquiry into press standards, following the phone-hacking scandal.

In his original terms of reference, it was envisaged the inquiry would be split into two parts.

The first, looking at the culture and practices of the press and relations between politicians, press and the police, took place in 2011 and 2012, with a full report in November 2012.

The second part was scheduled to consider the extent of improper conduct and governance failings by individual newspaper groups, how these were investigated by the police and whether police officers received corrupt payments or inducements.

- Published1 March 2018