Who spent what on Facebook during 2017 election campaign?

- Published

Last week we learned more about the political adverts on Facebook pumped into people's feeds ahead of last year's general election.

Using the site is free but getting noticed can be expensive.

The Electoral Commission has published a detailed breakdown of party spending in the run up to 8 June.

The figures show the Conservatives spent far more than Labour on Facebook - but their posts reached fewer people.

How much cash?

The figures break down how parties spent almost £40m during last year's general election campaign period:

Conservative and Unionist Party: £18,565,102

Labour Party: £11,003,980

Liberal Democrats: £6,788,316

Scottish National Party: £1,623,127

Best for Britain: £353,118

National Union of Teachers: £326,306

Green Party of England and Wales: £299,352

Women's Equality Party: £285,662

UKIP: £273,104

Theresa May's party paid Australian strategist Lynton Crosby's firm, CTF Partners, £4m to run their campaign, as part of £5.3m spent overall by the party on "market research/canvassing".

The Liberal Democrats spent £1.29m on market research/canvassing, while Labour spent just half that amount.

Spending on "unsolicited materials to electors" - things like leaflets - was more evenly split between the parties.

Lots of money went on various things classed as "advertising" - £5.3m overall spent by the Tories, £3.1m by Labour, £840,000 by the Liberal Democrats, £320,000 by the SNP, and amounts below £80,000 by the Green Party, Plaid Cymru and UKIP. Much of this went on things like billboards.

But an increasing amount is being paid to companies like Facebook and Google for online advertising, and to smaller companies which help parties target voters effectively online.

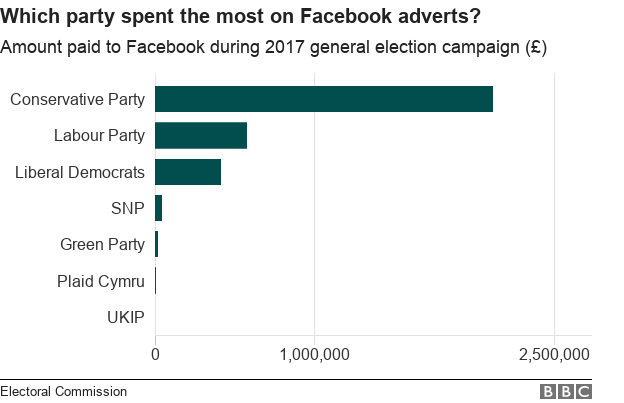

Of the £40m, parties spent around £3m directly on Facebook - and it wasn't evenly distributed. The Conservatives spent twice as much as all the other parties combined on Facebook.

Back in 2015 the Conservatives secured an unexpected victory after spending £1.2m on the social media site, about ten times more than Labour. Although it's hard to prove a direct link, clever use of Facebook advertising in marginal seats was one of the things credited with helping David Cameron's surprise win.

This time the Tories spent even more, but the party ended up going backwards, losing their majority in parliament.

Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party got far more views and shares online despite spending barely a quarter of the amount the Tories did. Labour only spent a little more than the Liberal Democrats who made far less of an impact online. So how did this happen?

The Liberal Democrats reached far fewer people than Labour on Facebook despite spending almost as much money

During the campaign BBC Trending ran a project called Filter Bubbles of Britain which tried to shed light on social media campaigning.

The project analysed parties' use of Facebook tools to target people with precise, localised messages based on their age, location and political affiliation. This is known as "microtargeting".

"It's a pattern we noticed in this election that wasn't really there, or we didn't really notice, in previous ones," says Mike Wendling, who headed the project.

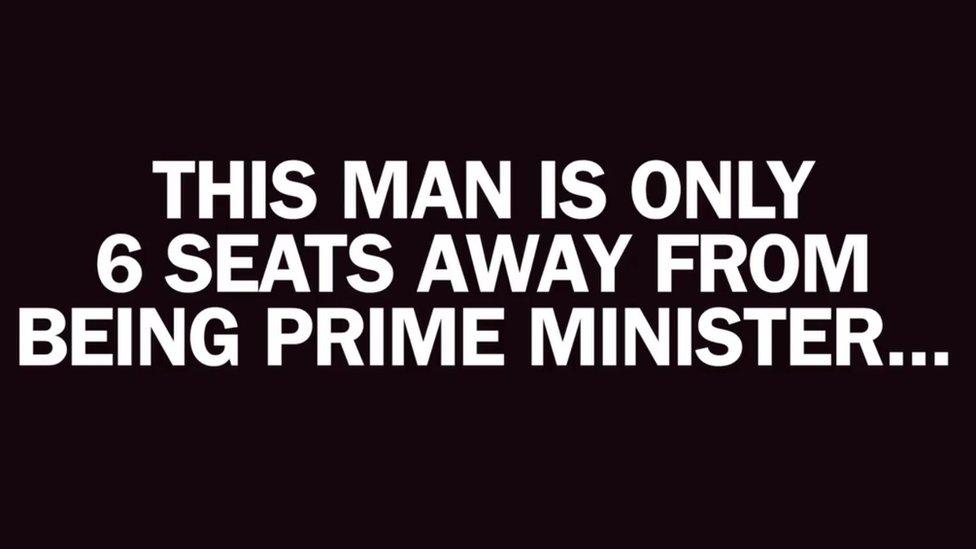

Wendling's team spotted one clear trend in particular: the Conservatives paying for numerous adverts attacking Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn or his close allies, particularly John McDonnell and Diane Abbott.

The most viewed video made by a political party during the campaign was a Conservative video attacking Mr Corbyn for being weak on defence. It was viewed more than 8m times.

A Conservative advert accusing Jeremy Corbyn of being weak on defence

The most watched video posted by the official Labour page - giving 10 reasons to vote for the party, a couple of days before the 8 June vote - got half as many views.

An election video posted by the Labour Party

Overall though, Labour's page posted far more videos, and they got far more views overall than videos posted by the Conservatives or other parties. Labour videos were often reposted multiple times, a tactic the Conservatives barely used.

Mark Wallace, editor of the website Conservative Home, has published a lengthy, critical account, external of how the operation which succeeded in 2015 failed to do so two years later.

"Lots of the data gathered for the 2015 election had been allowed to go stale, and the machine was caught off-guard," he told the BBC. "They had been letting people go in late 2016 on the assumption that the next election was still four years away."

Away from the parties' official pages, analysis by Buzzfeed News, external found that pro-Labour, anti-Tory news stories were far more widely shared online than articles supporting Theresa May's party.

While much of the mainstream print press was critical of Labour and its leader, several left-wing websites like Evolve Politics and The Canary were pushing the opposite view online.

Issues like fox hunting and the ivory ban did particularly well on social media, and were particularly likely to paint the Conservatives in an unfavourable light.

Since the election Environment Secretary Michael Gove has unveiled a raft of policies aimed at protecting animals,.

Disproportionate enthusiasm

Posting on Facebook is free of course, as is watching and sharing videos. Money just helps push videos in front of more people - but isn't always necessary for posts to do well.

Both parties paid for Facebook advertising, but Labour posts were far more shared widely by supporters and activists, a very effective form of free publicity. The Conservatives did not benefit from this "organic reach" in the same way.

Much of the Conservatives' messaging focused on the two leaders, arguing May would be better at negotiating Brexit

"Organic reach is the number of people who see a message without anybody paying for it," says Mike Wendling. "It's distinct from paid reach, which as the name implies is paid for."

There was "a disproportionate level of enthusiasm for Labour messages", says Wendling. "It's clear from the figures that organic reach was a crucial factor in mitigating the Conservative Party's large advantage in paid reach."

As well as posts from the official Labour page and Corbyn's personal one, the party benefited from lots of other content that pushed the party's message on social media but wasn't funded or directed by the party.

One example is the video "no one spits bars like Jeremy Corbzy", uploaded by JOE Media, an online digital publisher. It shows Corbyn's face superimposed onto that of rapper Stormzy, appearing to rap a list of policies.

A video of Jeremy Corbyn appearing to rap a list of policies got almost 9m views

Although it seems a trivial example, the video clearly distils many of Labour's key policies into a 38 second long video, and was aimed a young audience unlikely to watch a conventional political broadcast.

It has been viewed almost 9m times - more than any video posted by a major party during the campaign - and didn't cost Labour a penny to make or distribute.

If it had been aired by a broadcaster rules would likely have required it to be part of a balanced range of views. That is not the case online.

This video was also aimed at a group which is hard to reach through conventional political messaging. Young voters have been said to have played a significant role in last year's surprising result, although some recent research suggests reports of a surge in youth turnout may have been overstated.

There are many more examples like this. "Inside the Conservative campaign, they concede that they did not see this red tide coming," says Mark Wallace. "However, some of those involved did start to notice it as the campaign went on, and began to worry about whether it was having an impact."

Dark ads

Advertisers have always targeted things at particular groups - just flick through a magazine aimed at older women and one aimed at younger men to see the difference in ads - but the internet allows for more precision.

Everyone sees different Facebook adverts depending on their friends, location and demographic details like age and gender, as well as the things they 'like'. This makes it hard to track exactly what adverts people are seeing.

The organisation Who Targets Me, external tried to track political advertising during the campaign by crowdsourcing material from more than 10,000 users across the country.

"We had just launched our project when the general election was announced," said Maeve McClenaghan of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, which helped analyse the data during the campaign.

"We were well aware that everyone was talking about how this was going to be the 'dark ads' election."

Dark ads are tailored messages which can only be seen by a targeted audience. Whereas 'microtargeting' can simply refer to a public post being pushed prominently to a specific audience, "dark ads" will not be seen by anyone not targeted by it, making them very hard to track. They're perfectly legal.

In London the Conservatives were targeting voters with ads accusing Jeremy Corbyn of supporting a "garden tax" which would hit expensive homes in the capital the hardest.

Different messages were used in other parts of the country. In Derby, home to a Rolls Royce plant which works with nuclear material, voters saw adverts accusing Mr Corbyn of risking jobs in the nuclear industry.

An example of a hyper-targeted Conservative advert seen in Derby North. Labour won the seat

Closely targeted adverts are often negative according to Sam Jeffers of Who Targets Me. "If a party knows it can put their ads in front of people who will respond to them, but keep them away from people who won't, that's a great temptation."

Facebook says it is making advertising more transparent. In October the company announced new tools, external that will allow users to see all the ads a page is running, including "dark ads".

The tools are being tested in Canada with the intention of being ready for the US midterm elections this November. Facebook says it will provide details about election adverts including how much was spent promoting them, how many Facebook users they have reached, and the demographics of those people.

Facebook also says political advertisers will have to verify their identity under the new rules. Before and after the 2016 US election, Facebook said, about 80,000 posts were uploaded by Russia-based operatives.

In the UK last year, although much of the media attention during the campaign focused on Tory "dark ads", Labour used the same tactics according to an analysis by Buzzfeed News, external.

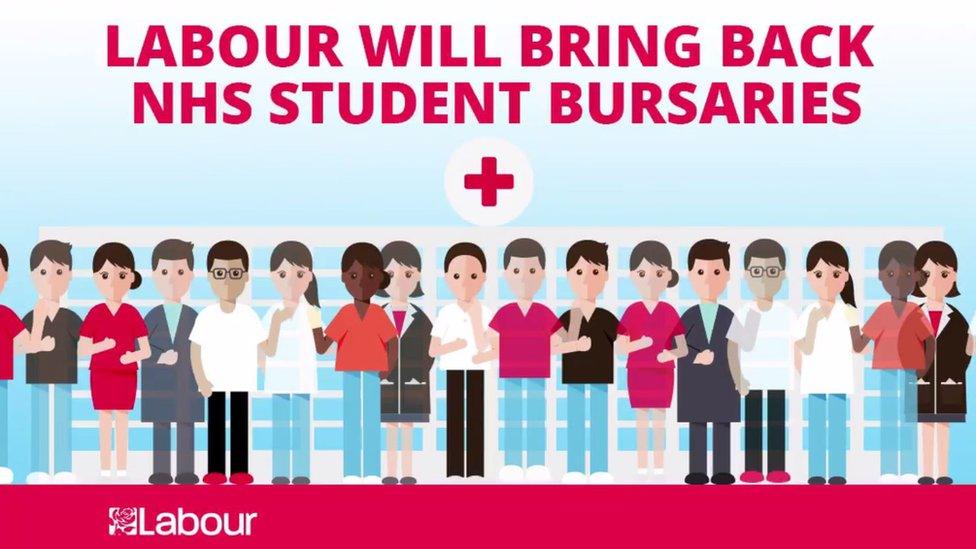

Buzzfeed cited a Labour source as saying that potential voters who raised concerns about the NHS on the doorstep would then have that information fed into voter databases, and the voter would then receive targeted Facebook posts.

Labour targeted voters who expressed concern about the NHS with relevant videos and posts

Psychological profiling?

Compared with broadcast media, online political messaging is far less regulated. Broadcasters are under strict political balance rules. The same model does not apply online.

Sam Jeffers of Who Targets Me thinks the rules should be tightened up: "There is very little visibility of the data being used to target people."

At the moment tech giant Facebook and data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica are at the centre of a dispute over the harvesting and use of personal data, and whether it was used to influence the outcome of the US 2016 presidential election or the UK Brexit referendum. Both sides deny any wrongdoing.

There is no suggestion Cambridge Analytica had any involvement in the 2017 general election.

"[Parties] seemed to be targeting people based on location, age and quite broad 'likes', rather than the Cambridge Analytica stuff where the suggestion is they can do very heightened psychological profiling," the Bureau of Investigative Journalism's Maeve McClenaghan told the BBC.

Not just Facebook

Money paid directly to Facebook does not give the full picture - parties also paid consultancies and agencies to help better target voters via social media and email as well as traditional methods like door-knocking and sending leaflets.

Cash was also paid to other tech companies including around £1m to Google. The Conservatives spent about £500,000 with the company, Labour about £210,000, and the Liberal Democrats around £170,000.

A lot of this went on adverts on YouTube, which is owned by Google. All the main parties were running adverts on the video sharing site during the campaign. However Labour, the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats pulled their material after an investigation by the Times, external revealed adverts were being promoted next to videos of Islamic extremists.

Not very much was spent on Twitter advertising - just £56,500 by all parties combined.

One of the more unusual pieces of electoral expenditure shows up in the Electoral Commission database as two separate payments from Labour to 'Snap Group Limited' in the final week of the campaign, totalling around £64,000.

This money went on a Jeremy Corbyn Snapchat filter and other adverts on the picture-sharing app which is popular with teenagers.

A spokeswoman for the Labour leader told the BBC the Corbyn filter was viewed 9m times according to data provided to the party by Snapchat.

Labour used Snapchat as a campaigning tool during the election campaign

The Corbyn filter was UK-wide but conventional adverts - videos that pop up between your friend's posts - were geographically targeted, the spokeswoman said. "The adverts were in places that made sense, like universities."

The Conservatives filed an expense for £17,800 to Snap Group Limited a month after the election, but the party's activity on the app does not seem to have had nearly as much reach as Labour's.

Other groups

Aside from the parties, other groups played a big role too - such as Momentum, a pro-Jeremy Corbyn grassroots group which has shifted the centre of gravity within the Labour Party from centrist MPs to left-wing activists.

The group racked up huge numbers of views on Facebook during the campaign with eye-catching adverts such as one called "Tory Britain 2030", external painting a gloomy picture of a country struggling after successive Conservative election wins. It was viewed 7 million times in one week.

Videos posted by Momentum, a pro-Jeremy Corbyn grassroots group, during the election campaign

Although Momentum videos were viewed millions of times on Facebook, the group declared less than £4,000 in payments to the company and less than £40,000 overall. Momentum is currently being investigated by the Electoral Commission over allegations it broke finance rules. The group says it is cooperating with the investigation which it says refers to "administrative errors that can be easily rectified".

Last week's Electoral Commission figures, external list the seven political parties which spent more than £250,000 in the year before election day (on everything, not just online advertising).

It also gave details about two other groups. Best for Britain is a pro-EU campaign group which spent £350,000 supporting candidates opposed to a "hard Brexit". Like the big parties, Best for Britain used different adverts for different audiences according to Maeve McClenaghan of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, external.

An advert featuring the photograph of a middle-aged woman appeared in the Facebook feed of a 46 year-old in Tynemouth in the North East, while one featuring a young woman was seen by a 24-year-old woman in Wimbledon, South-West London.

The Best for Britain campaign used different adverts for different demographics

The other organisation to make the list was the National Union of Teachers (NUT). It spent £326,306 in the year up to the 8 June 2017 poll, more than UKIP and the Greens.

The NUT campaigned heavily on the issue of school funding - and education rose in prominence during the campaign according to Ipsos Mori, a polling firm, external.

Most of the money spent by the NUT went to printing firms - presumably for leaflets, flyers and other old-school methods of political communication.

But about a third went to an agency called Small Axe Communications, which built an interactive map, external showing people "the scale of school cuts in their constituency and where Parliamentary candidates stood on the issue."

The company claims to have "reached 3,180,321 people across the country through targeted Facebook ads in target constituencies".

School funding increased in prominence as an issue during the campagin

An NUT explainer video titled "The Truth About School Cuts" was viewed 4.8m times on Facebook. It used images of Theresa May and was critical of Conservative policies on education - so presumably benefited opposition parties, especially Labour.

Both the NUT and Best for Britain are under investigation by the watchdog for allegedly submitting an incomplete spending return, while Best for Britain is also facing questions for allegedly not returning a £25,000 donation from an "impermissible" donor within the 30 days required by electoral law.

"Best for Britain's audited spending return was filed on time, together with supporting documentation and the requisite auditors report," a spokesman said. "We are dealing with the questions raised with us by the Electoral Commission, some of which have already been answered, and will offer whatever further assistance they may require."

What about next time?

If these examples seem a bit imbalanced, it's because the digital election campaign last year was imbalanced. Official Labour content tended to do better than Conservative content, with organic shares and outside groups overcoming the difference in cash spent on Facebook advertising.

However just because Labour seemed to benefit last time, that won't necessarily always be the case, says Mike Wendling.

The Conservatives used Facebook very effectively in 2015, and examples from abroad show it is not always left-wing parties which benefit from digital campaigning.

"The same pattern could be seen in the US 2016 Presidential election, where memes and posts in pro-Trump groups were widely shared among really enthusiastic people," says Wendling.

The next general election - whether it is in May 2022 as currently planned, or earlier - will be fought on very different turf. The social media landscape has changed dramatically even since last June, so who knows how it'll look in four years' time.

Maeve McClenaghan says the 2017 general election campaign was very unusual because of the way it started - Theresa May announced it on April 18 with absolutely no warning.

"The snap election took everyone by surprise, including the Tories' social media team," she told the BBC. "It may be that next time we have an election, things are more sophisticated."

Conservative Home's Mark Wallace agrees: "Last year's pretty dire experience has delivered a wake-up call to the Conservative Party that is very hard for anyone to deny."