Revealed: Letter that stopped Jeremy Thorpe giving evidence

- Published

Gay rights campaigners protested about the way homosexuality was treated in the trial

It was dubbed "the trial of the century" - a dashing, charismatic political leader accused of conspiring to murder his former gay lover in a bizarre, ill-fated plot.

But why did Jeremy Thorpe - leader of the Liberal Party and pillar of the Establishment - not go into the witness box to defend himself from charges he vehemently denied?

The BBC has obtained a document that sheds new light on the decision by Mr Thorpe's lawyers not to let him give evidence at the Old Bailey in 1979, seen at the time as a high risk manoeuvre that might have led to a lengthy prison sentence for their client.

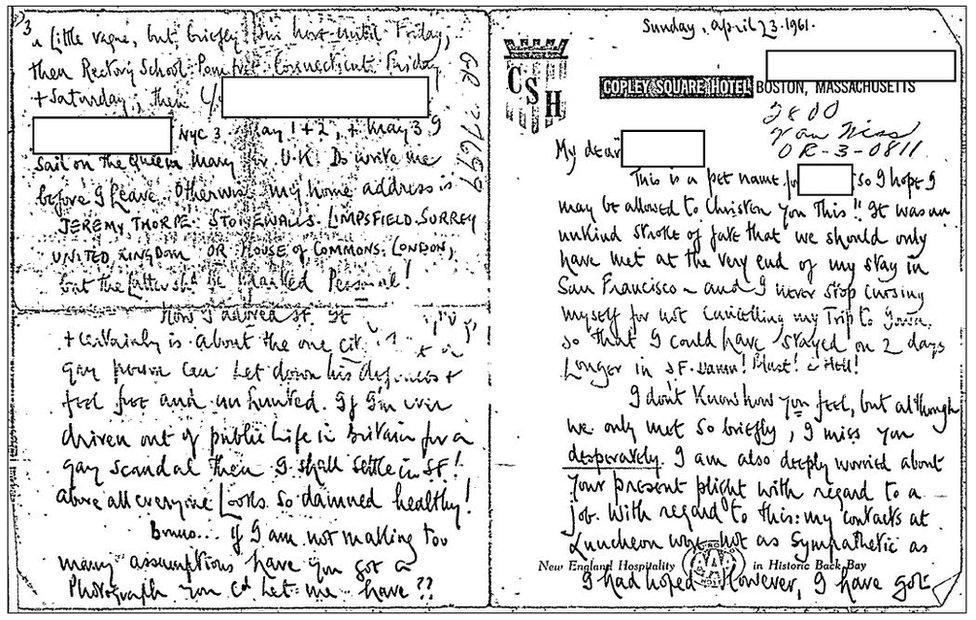

It is a passionate four-page letter from Mr Thorpe to an American man called Bruno sent after they had met in San Francisco in 1961, which Mr Thorpe wrote is "the one city where a gay person can let down his defences and feel free and unhunted".

The prosecution at the trial had a copy, and if Mr Thorpe had given evidence he would have faced questioning about his sexuality which he wanted to avoid.

I received the "Bruno letter" and connected records from the US Federal Bureau of Investigation after making an FOI request under American Freedom of Information law.

In it, Mr Thorpe also said of San Francisco: "If I'm driven out of public life in Britain for a gay scandal I shall settle in SF!"

He asked Bruno to write to him at the House of Commons "marked Personal!", and discussed how they could meet again, adding: "I must get on to SF on some mission, which the British or American taxpayers will pay for!!"

Pages one and three in the FBI's copy of Thorpe's letter to "Bruno"

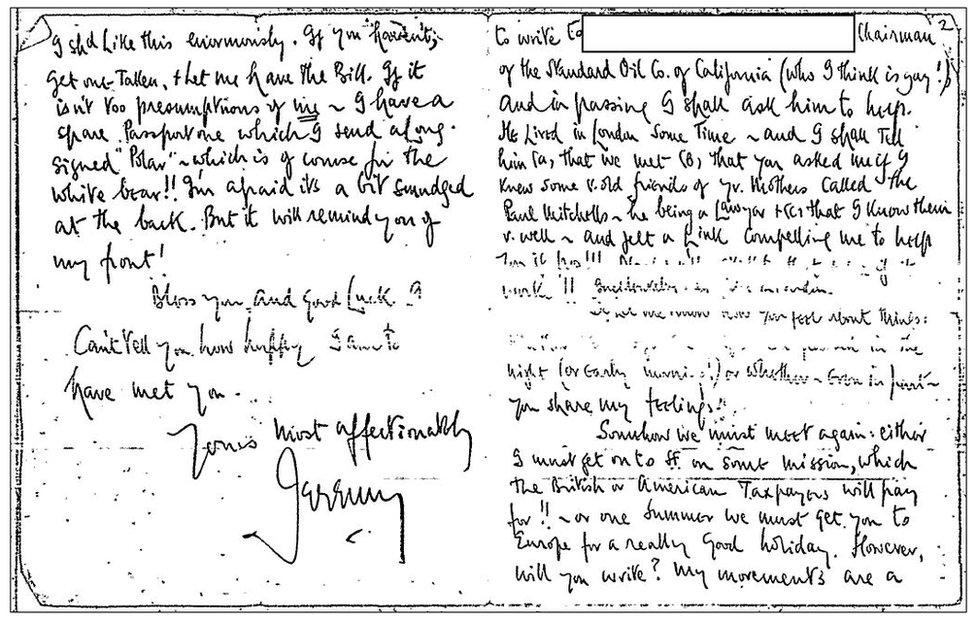

Pages two and four in the FBI's copy of Thorpe's letter to "Bruno"

Mr Thorpe, a former leader of the Liberal party, and three others were acquitted of conspiring to murder his former lover, Norman Scott, in one of the most famous court cases in British political history.

The trial arose from a bizarre incident on Exmoor in which Mr Scott's dog Rinka had been shot dead.

The prosecution asserted that the real plan had been to kill Mr Scott himself, whom Mr Thorpe wanted to silence because he was telling others about their past relationship, a relationship which the former Liberal leader persistently denied.

During the court case, many observers were stunned when Mr Thorpe's legal team announced he would not give any evidence in his own defence.

This meant that he avoided being cross-examined by the prosecution and personally having to respond to a range of uncomfortable topics.

They included evidence of mysterious financial transactions and remarks he had made about wanting Mr Scott dead, which were part of the alleged conspiracy; but also evidence of his affairs at a time when, until 1967, male homosexuality had been illegal.

Prosecution lawyers had notified Mr Thorpe's barrister George Carman and solicitor Sir David Napley that they had significant information on his other gay relationships, including the missive to Bruno.

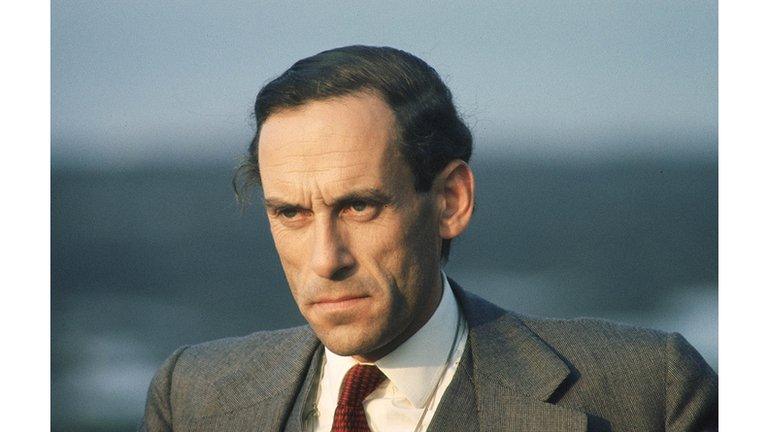

Jeremy Thorpe arriving for his trial

According to the biography of Mr Carman, written by his son Dominic, the barrister was already inclined to think that Mr Thorpe should not give evidence and the Bruno document "removed any doubt" he had that it was the right decision.

The significance of the letter is confirmed in an earlier book on the Thorpe affair, Rinkagate, in which the journalists Simon Freeman and Barrie Penrose state: "Any lingering doubts that Carman and Napley might have had were removed when the prosecution showed them a sexually explicit letter from Thorpe to a friend called Bruno... Carman and Napley agreed it would be a catastrophe for Thorpe if the letter became public, which would definitely happen if he gave evidence."

The decision not to go into the witness box was Mr Thorpe's legal right.

The reason he later gave in his own memoirs was that giving evidence "would have prolonged the trial unnecessarily for at least another 10 to 14 days".

Hugh Grant plays Mr Thorpe in a new BBC drama

After the not-guilty verdict, it was widely considered to have been a clever strategy from his legal team.

The three key prosecution witnesses all faced significant doubts over their credibility, and they failed to convince the jury.

However, in public relations terms it was much less successful.

Mr Thorpe's acquittal did not seem to clear him in the court of public opinion.

His reputation never recovered from the allegations in the case and the widespread feeling they had not been satisfactorily answered, until he died in 2014.

Interest in the trial has recently been reawakened by the forthcoming BBC One series, A Very English Scandal, which dramatises the events of the Thorpe-Scott affair and the ramifications of their falling out.

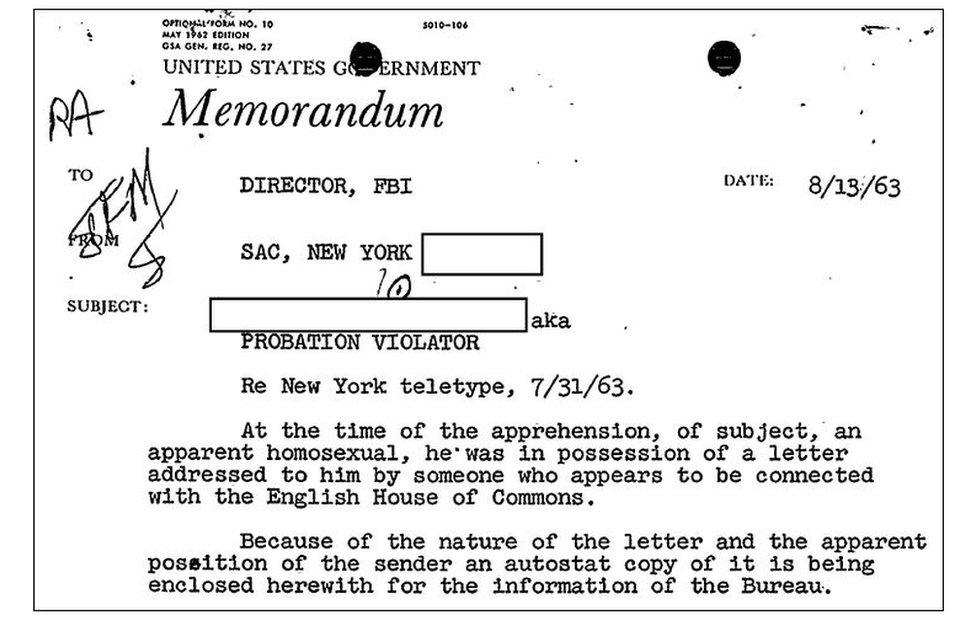

The FBI found the letter in Bruno's possession when they arrested him in 1963 for breaking a probation order he had earlier received for theft.

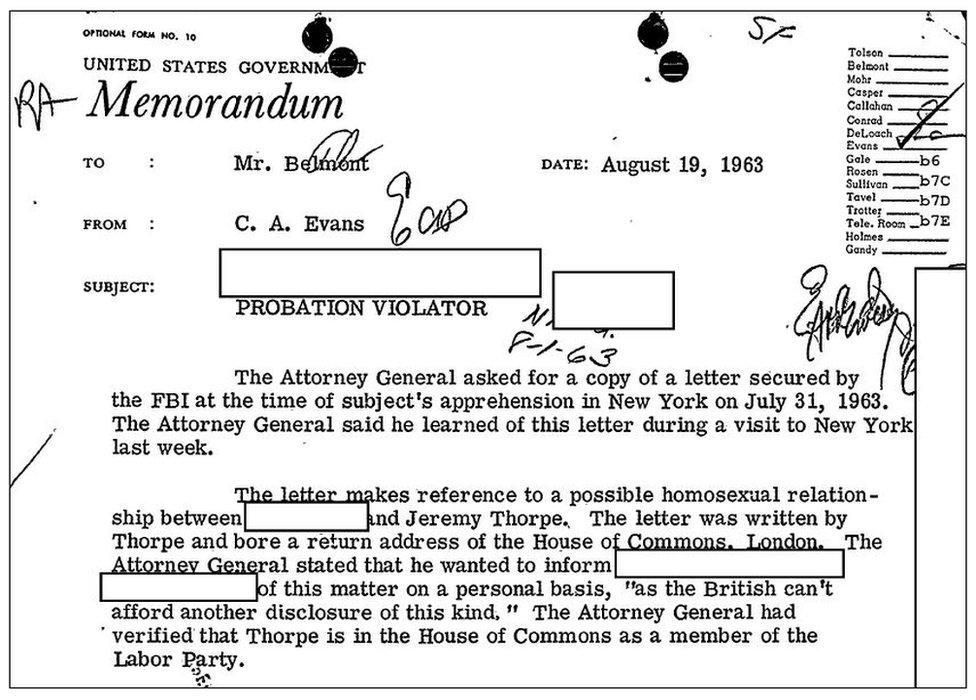

As it indicated the writer was a British member of parliament, the document was passed to the authorities in London, although the FBI's files show they mistakenly thought Mr Thorpe was a Labour rather than a Liberal MP.

The US Attorney General, Robert Kennedy, brother of the then president, wanted personally to inform someone whose name is redacted from the FBI's release but given the context, was probably in the UK government.

According to the FBI records, Mr Kennedy said: "The British can't afford another disclosure of this kind."

This was presumably a reference to the Profumo and Vassall sex scandals which had shaken the British establishment at that time.

War Secretary John Profumo resigned after the disclosure of his affair with Christine Keeler, a young model also involved with a Russian spy.

British diplomat John Vassall was caught after years of passing secrets to the Russians, having been blackmailed by the KGB because of his then illegal homosexuality.

In due course the Thorpe scandal was to become equally sensational.

You can follow Martin Rosenbaum on Twitter as @rosenbaum6, external

- Published4 December 2014

- Published4 December 2014

- Published6 December 2014