Jeremy Thorpe: Memories of infamous Liberal politician strong in Devon

- Published

Through his rise and fall, Jeremy Thorpe put North Devon on the political map

Jeremy Thorpe was elected leader of the Liberal Party in 1967. In the decade which followed, he put North Devon, his constituency, on the map.

I was born there and grew up "where Exmoor meets the sea", as travel guides like to describe my village and the area around it.

Jeremy Thorpe was our local MP; impossible to ignore, not because of the trilby hat or his Edwardian suits - which, even in a place not known for being cutting edge, were regarded as old-fashioned - but because of his charisma.

One of the biggest political scandals of the century destroyed his leadership. In 1979, he was put on trial at the Old Bailey, accused of inciting, and conspiring with others, to kill Norman Scott, a former lover. He, and the other defendants, were all acquitted.

This is the story told in A Very English Scandal, a three-part drama which begins on BBC One which starts on Sunday, at 21:00 BST. It stars Hugh Grant and Ben Wishaw as Thorpe and Scott.

Until his defeat at the general election, weeks before the trial began, Thorpe had held his constituents spellbound. One local vicar was so admiring that he held a special church service after Thorpe's acquittal, calling the MP "blessed". The local Archdeacon was horrified, denouncing the service as "unfitting, unseemly and unsavoury".

I hadn't heard the late Reverend John Hornby's voice for decades, but it took me right back to my childhood. Melanie, his wife, was my primary school teacher.

Thorpe had political opponents, but even they acknowledged that having him as the local MP had made a difference.

Sir Nick Harvey, who eventually won the seat back for the Liberal Democrats in 1992 and held on to it for another 23 years, told me that many of the big employers operating in North Devon today were first lured down there by Thorpe's indefatigable sales pitch, lubricated by grants from Harold Wilson's government in the 1960s.

Thorpe was acquitted after a sensational trial in 1979 but spent the next 25 years in political exile

He helped to save one of the three rail branch lines that used to serve the area, and lobbied for the road link to the M5 which was approved just before he lost his seat.

Trawl images of Jeremy Thorpe and you'll quickly see why he stands out. Whilst many of his fellow politicians were as stiff and formal as their collars, Thorpe was a natural show off. During one of his three general elections as Liberal leader, he hired helicopters and hovercraft.

There's a photo from 1966 of him, broom in hand, outside a village post office and general stores. The owners hadn't had a holiday for years. When he found out, he offered to run the store for a week so they could have a break. He did just that, but of course made sure that he got publicity for it.

Remember David Cameron and Nick Clegg sealing their coalition pact with a gushing news conference in the rose garden at No 10? That could have happened in February 1974.

Both Edward Heath, the Conservative prime minister who had just lost his parliamentary majority, and Thorpe wanted a coalition, but talks foundered over reform of the voting system.

It's not hard to see why Thorpe might have convinced himself that the Liberals, who hadn't held any government office in peacetime since the 1920s, were on the brink of a breakthrough. Perhaps that explains, though it certainly doesn't excuse, his increasingly desperate attempts to silence Norman Scott.

To have a homosexual relationship was no longer a crime, but there still weren't any openly gay MPs. Thorpe, widowed after the 1970 election, had re-married, tempering his political radicalism with domestic conventionality.

Yet, as documents recently discovered by the BBC revealed, the gay side of Thorpe's life was messy. The MP had been reckless.

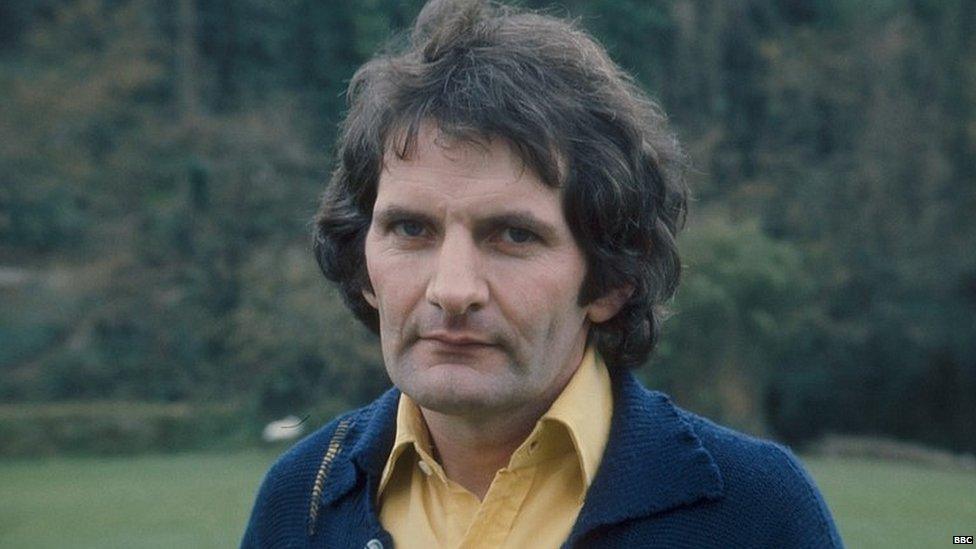

As played by Hugh Grant in a new BBC drama, the Liberal politician had a distinctive sartorial style

On my visit to north Devon, I met Stella Levy, at the art gallery she co-owns in Barnstaple. In the late 1960s, she was a model, worked with Norman Scott, and has been friends with him ever since.

By coincidence, Stella and her late husband bought a holiday home in North Devon. Eventually, when they left London altogether, they bought a house in Cobbaton, a tiny village outside the town. She was astonished to discover that one of the neighbours was the local MP.

Stella says she had always believed Norman Scott when he told her of the affair with Thorpe, but had some doubts about some of his more lurid anecdotes. She found Thorpe charming, and attended some of the fund-raising coffee mornings at the MP's home.

In the years since the Thorpe trial, she's kept her views to herself, conscious that many people locally remain passionately loyal to Thorpe's memory. That changed, though, when a release of government papers under the 30-year rule revealed a letter sent by Thorpe to Harold Wilson, then prime minister.

Increasingly desperate to discredit Scott, Jeremy Thorpe suggested that the Levys, with whom Scott sometimes stayed, were running a vice ring. His "evidence" was that the Levys had installed a sunken bath.

Some of Thorpe's constituents, as well as a prime minister with a 1920s Yorkshire Methodist upbringing, might have thought that a bit unconventional.

Stella laughs at the idea that a spare bathroom, used on visits by the three children from her husband's first marriage, could be mentioned by Thorpe in this way. What she doesn't find at all funny, though, is his duplicity.

Although she now feels no sympathy for a man who chose to play with fire and got burnt, she accepts that many locally will simply refuse to believe what they see on their television screens.

Thorpe had a sniff of power in 1974 when he held talks with Edward Heath on forming a government

Were it not the story of a man who spent more than a decade being threatened, hounded and abused, and who came to live in fear for his life, A Very English Scandal could be told as farce.

There's the murder plot itself - if there was one, which the jury didn't believe - which involved dropping Scott down the shaft of a disused mine; there's a vicar who conducted exorcisms in a local health centre; a would-be assassin who went looking for Norman Scott in Dunstable in Bedfordshire rather than Barnstaple in Devon.

Most bizarre of all is the case of the dead dog in the night.

Rinka, Scott's dog, took the bullet on a storm-lashed night on Exmoor in October 1975.

This incident was the catalyst for the destruction of Jeremy Thorpe's career; the trail of animal blood would lead inexorably to court number one at the Old Bailey.

It was the off-duty AA man from my village who stumbled on Scott after the dog killer had driven off.

Mouldering away somewhere in my dad's garage are the scrapbooks, in which I preserved the story, cutting out pages from The Daily Mirror and the local paper, the North Devon Journal Herald.

The trial, election defeat and the effects of Parkinson's disease condemned Jeremy Thorpe to exile from public life but not entirely from politics.

Details of the plot that culminated in the killing of Norman Scott's dog Rinka took years to fully emerge

Sitting in Barnstaple's Liberal Club, Sir Nick Harvey tells me the man he met in 1990, when he was first selected to fight the seat, remained fully engaged locally.

He threw himself into fundraising and strategising for Sir Nick's ultimately successful first election campaign here.

Arriving to inspect the boards to be erected in gardens, front yards, and - in this large constituency with its scattered communities - fields, Thorpe asked whether they were flammable, He well knew some of the tricks enthusiastic campaigners sometimes got up to.

The photographs on the wall in the Liberal Club include the torch-lit victory parade the night after Sir Nick was elected. Stooped but instantly recognisable is Thorpe, walking side by side with his successor.

The procession mirrored the way Thorpe had celebrated his first election, an idea Thorpe had hit upon after hearing from local veterans that this was how Barnstaple's Liberals had celebrated the Liberal Party landslide of 1906.

Tradition mattered to Jeremy Thorpe. He was the only party leader of the Twentieth Century never to be offered a peerage. Sir Nick says Thorpe, though loyally supported by party members locally, felt acutely the national party's unwillingness to honour him. "For Liberals, we weren't very liberal," is Sir Nick's verdict.

There was one more public appearance, on the floor of the Liberal Democrat party conference in 1997.

He also attended the unveiling of his portrait at the National Liberal Club, in London, putting him alongside William Gladstone, Liberalism's grand old man, Henry Asquith, the last prime minister to lead a Liberal Party government, and David Lloyd George, his own political hero.

I only met him once, when he was the guest of honour at our village's annual children's party. That he turned up in the frozen gloom of a Saturday afternoon in January, bringing a splash of celebrity and colour, was something even a little boy not quite ten years old recognised was special. Jeremy Thorpe swept into the hall, smiling and shaking hands, sharing jokes and scones with jam and cream.

Then he went away and our little corner of the world was back in black and white again. I still think we've not quite got over it.

Listen back to Shaun's feature on Radio 4's The World Tonight