Alternative ways to break Brexit deadlock

- Published

Theresa May is making a last ditch bid to save her Brexit deal after suffering a crushing defeat in a Commons vote on it.

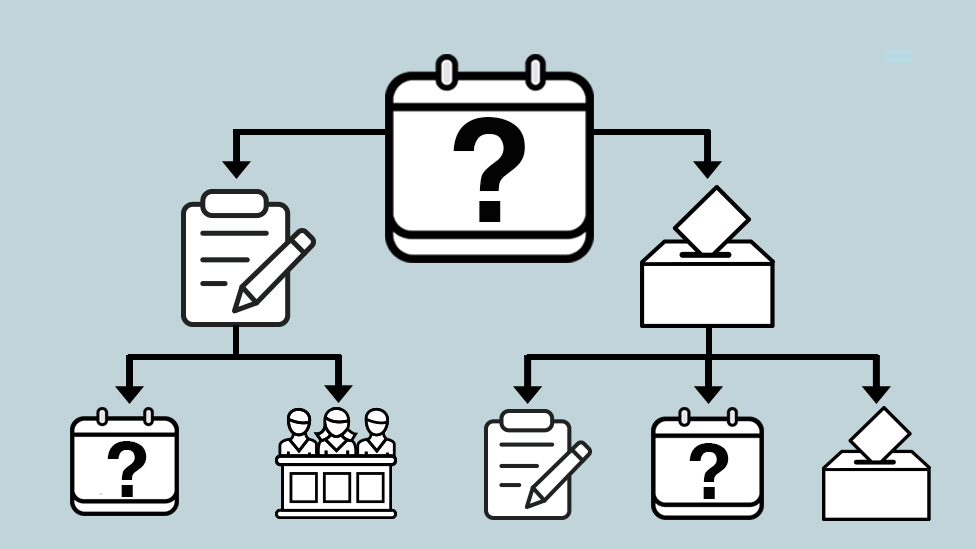

Britain is still on course to leave the EU, but nobody knows whether it will be with a deal or not, or whether there will be a general election or a second referendum.

You can read about all the likely scenarios here.

But here are some alternative ideas that a few weeks ago seemed highly unlikely but which could, in these extraordinary times, start to look like contenders.

Cancel Brexit

The European Court of Justice has ruled that Britain can revoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty - the legal mechanism taking the country out of the EU on 29 March - without the approval of the other 27 member states.

This turns previous assumptions about Brexit on their head, and gives hope to those who believe it has all been a terrible mistake.

There is some debate over how the government would go about cancelling Brexit. And given the divided state of Parliament, it is hard to see how any prime minister could get backing for such a move without a further referendum.

Theresa May ruled it out on the grounds it would be seen as a betrayal of the 17.4 million people who voted to leave in 2016.

European Council President Donald Tusk has hinted that cancelling Brexit would be his preferred option, tweeting, after Mrs May's deal was defeated by 230 votes: "If a deal is impossible, and no-one wants no deal, then who will finally have the courage to say what the only positive solution is?"

The Queen intervenes

With no apparent parliamentary majority for any single course of action - is it time to get the Queen involved?

In Britain's constitutional monarchy, this is not meant to happen. Her Majesty has always remained above the political fray and will, no doubt, want to stay that way. But she is the only person who can invite someone to form a government and become prime minister.

And if Theresa May loses a no-confidence vote in the Commons - and Labour has not ruled out tabling further such motions after Theresa May won the vote on 16 January - then this power could come into play.

There would be a 14-day period during which the Queen could ask someone to form a new government if it was clear they could command the confidence of the House. That could be Labour or another Conservative government or a cross-party government.

The Queen would not be able to exercise her own political judgement - everything would depend on whether the would-be new prime minister is deemed to have a realistic chance of getting their laws through Parliament.

The nightmare scenario, for the Queen and her advisers, is where it's not clear who has the best chance of winning a confidence vote but different people are making competing claims. If after 14 days, a new government cannot gain MPs' confidence, a general election will follow. There could be multiple confidence votes, or none, before the 14-day deadline.

One thing the Queen can't do is dissolve Parliament and trigger a general election. The monarch was stripped of that power by the 2011 Fixed-term Parliament Act.

A Citizens' Assembly

Brexit is not the only controversial issue to be put to a public vote recently - and some countries, such as the Republic of Ireland, before a referendum on overturning to its ban on abortion, have turned to a "citizens assembly" to find a way forward.

In Ireland, the body was set up to advise elected representatives on a number of ethical and political dilemmas. It is made up of 99 members chosen at random to broadly represent the views of the Irish electorate, and a chairman.

Citizens' assemblies are meant to give their members time to learn about an issue through discussions led by experts and then reach a conclusion through a series of votes.

The Guardian backs a citizens' assembly, external to sort out Brexit, arguing in an editorial that Parliament should have the right, if it chooses, to put the ideas the assembly produces to a referendum.

Left-wing campaign group Compass is another backer, and is supported by Labour MP Liz Kendall, former Archbishop of Canterbury the Right Reverend Lord Williams and Blur front man Damon Albarn, among others.

Green MP Caroline Lucas was reported to be planning to raise the citizens assembly plan with Theresa May when she met the prime minister to discuss Brexit compromises, after the PM's Brexit plan was voted down.

Liz Kendall suggests a "citizens' assembly of ordinary people", as used in Ireland, to ask UK voters about Brexit

Senior backbenchers take control

Nick Boles MP, co-architect of a plan for backbenchers to draw up a compromise plan

This was a scheme dreamed up by Conservative backbencher Nick Boles and two colleagues, Nicky Morgan and Sir Oliver Letwin, who want a softer Brexit than the one being promoted by Mrs May.

Mr Boles has put forward legislation, the European Union Withdrawal Number 2 Bill, that would give the government three weeks to seek a compromise and leave as planned on 29 March.

If his bill failed to get through the Commons, the three MPs had planned to push for a solution that takes the job out of government hands. Instead, the 36-strong House of Commons Liaison Committee, external would have been tasked with coming up with its own compromise deal.

The committee, comprised of chairmen and women of the Commons select committees and other parliamentary committees, meets periodically to give the prime minister a grilling on issues of the day. It has not previously been pressed into action to come up with policy ideas.

Its members span every shade of opinion on Brexit, from Conservative Remainers such as Sarah Wollaston to veteran Eurosceptics Sir Bill Cash and Bernard Jenkin. There are also Labour and SNP figures, and one Lib Dem.

Whether they could do a better job than the cabinet of agreeing a Brexit deal is an open question.

And they have now rejected the proposal, with the majority of members saying at a meeting on Wednesday, 16 January that they felt they were not equipped to draw up legislation.

There was also anger at what was seen as an attempt to bounce the committee into accepting Mr Boles's plan, although it is understood there are likely to be further moves to give Parliament a decisive role in deciding the way ahead on Brexit.

Two referendums

A cross-party group of MPs, under the People's Vote banner, is pushing for another EU referendum.

But what would the question be? A direct "Remain or Leave" re-run of the 2016 vote? Leave with a deal or no-deal? Or a combination of the two, with potentially three questions?

Vernon Bogdanor, professor of government at King's College, London, has suggested the Brexit impasse could be resolved by holding a further referendum - then another one. He wrote in the Guardian, external that two referendums could be held a few weeks apart - the first, a straight Leave or Remain choice. Then, if Leave won, another vote on the terms of departure.

Former cabinet minister Justine Greening has suggested an alternative - one referendum offering three choices, with people getting a first- and second-preference vote.

A government of national unity

Winston Churchill's wartime coalition with King George VI

Could a cabinet made up of different parties, usually formed during a time of national crisis, offer a solution?

It may seem like a concept confined to the history books - stirring up memories of Winston Churchill's wartime coalition or Ramsay MacDonald's 1930s national government, but it has been publicly floated as a way out of the Brexit stalemate.

Advocates of such an arrangement have included Tory pro-Remain MP Anna Soubry, who suggested Mrs May should reach out to the SNP, Plaid Cymru, Labour backbenchers "and other sensible, pragmatic people who believe in putting this country's interests first and foremost".

Her fellow Tory backbencher Sir Nicholas Soames, Churchill's grandson, has also backed the idea.

Both the Labour and Conservative front benches rejected the suggestion last summer - but it was revived by Remain-supporting Conservative MP Nicky Morgan in December.

However, Ramsay MacDonald's decision to form a national government was considered a betrayal by many in the Labour Party, in the early 1930s. And the electoral battering suffered by the Lib Dems after going into coalition in 2010 will still be fresh in many minds.

A Parliamentary Commission

A Parliamentary Commission, made up of senior figures from the Leave and Remain sides of the debate, to oversee Brexit, is another idea that has been raised by MPs. There was a lot of talk about this in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 referendum. Heavyweight figures, including Nicola Sturgeon, Lord Hague, Sir John Major and Yvette Cooper backed it.

It is probably far too late to set up such a body to oversee the UK's withdrawal from the EU, on 29 March. But the idea might regain some traction if trade talks get under way after Brexit day or if the Brexit deadline is extended.

But MPs are not meant to tell governments what to do, just scrutinise the decisions of ministers and hold them to account. So the danger is it could end up being a talking shop with no real power.

- Published7 December 2018

- Published7 December 2018

- Published13 July 2020

- Published7 December 2018

- Published7 December 2018