Brexit: What is Common Market 2.0?

- Published

A group of Labour and Conservative MPs is promoting what they call Common Market 2.0 as an alternative model for the UK's future relationship with the EU after Brexit.

You may have also heard it referred to as Norway Plus.

The MPs promoting it say it would go back to the sort of economic relationship the UK had with the European Economic Community in the 1970s and 80s, without having to be involved with closer political union or the direct involvement of the European Court of Justice.

They also say it could be agreed with the EU quickly and that there could be a majority for it in the House of Commons.

Critics point out that it would still involve freedom of movement, making significant contributions to the EU Budget and following EU regulations without membership of the bodies that create them.

It crosses several of Theresa May's red lines.

How would it work?

The European Economic Area, external (EEA) includes all 28 EU countries and three nations that are not members of the EU: Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, which are part of the Single Market but not the EU or its Customs Union.

They are members of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), along with Switzerland, which is not part of the EEA, having single market membership as a result of a complicated set of trade deals with the EU.

They make substantial contributions to the EU budget, and have to follow many EU rules and laws.

EFTA members are not part of the EU's Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) or the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), so they can set their own policies in those areas.

They are also exempt from EU rules on justice and home affairs.

What about the Customs Union?

EFTA members are not members of the EU Customs Union, which means they can sign their own trade deals with other countries, but they do not benefit from EU trade deals with other countries.

There have to be some customs checks on goods travelling between EFTA countries and EU countries.

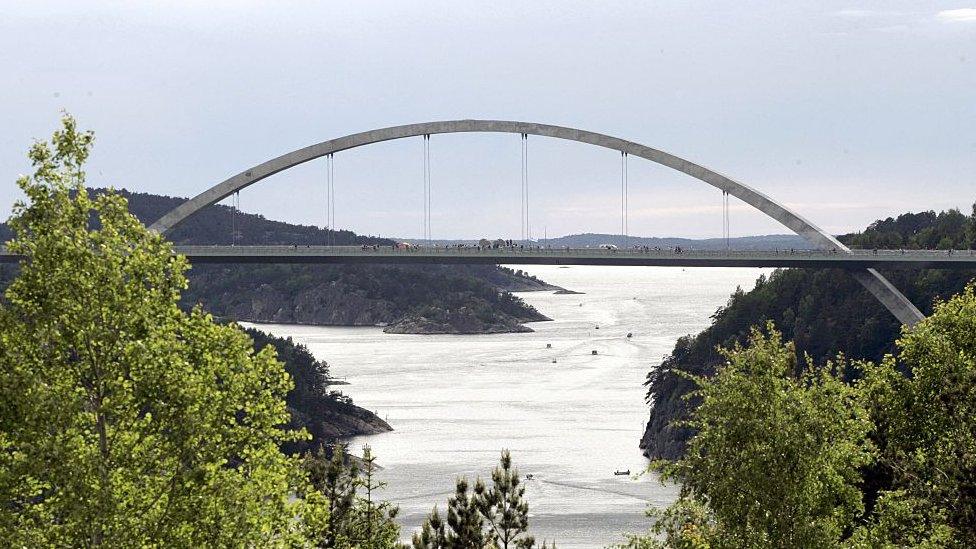

Norway's border with Sweden, for example, is one of the most frictionless in the world between two countries that do not have a customs union, but it still takes about 20 minutes on average for a lorry to pass through its main border crossing at Svinesund.

Svinesund Bridge is a border crossing between Sweden and Norway

This is a problem for the Common Market 2.0 plan because in order to prevent a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, its supporters are proposing that there should be a customs arrangement that basically mirrors the Customs Union.

It is the extra customs arrangement that makes the proposed solution a "Norway plus" deal.

But having that sort of customs arrangement would be against EFTA's current rules.

How much would it cost?

As an EFTA member, the UK would continue to make contributions to the EU Budget.

They would be calculated based on which EU programmes the UK wished to continue to be involved with.

It is likely that the bill would be considerably lower than it is as an EU member.

It's not clear exactly how much lower it would be, with estimates ranging between two thirds and 88% of the current level, which is about £9bn a year on average.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

What about having no say in the rules?

When the EU adopts a measure that is relevant to the single market, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein have to bring it into their domestic laws.

The three countries do not get seats in the European Parliament, membership of the European Council or the right to appoint a commissioner, but they do have some influence over legislation.

At the early stages they sit on committees at the European Commission, and they are entitled to submit comments on upcoming legislation.

At a later stage, they can challenge a new law relating to the single market via the EEA Joint Committee, which includes representatives of the EU as well as the three countries.

Through that body, they may secure exemptions from new laws and regulations.

Could freedom of movement be restricted?

EFTA members have to follow the four freedoms of the single market - freedom of movement of goods, services, capital and people.

That means people from across the EU are free to live and work in EFTA countries, and people from EFTA countries can live and work across the EU.

But the MPs promoting Common Market 2.0 have suggested that EFTA rules could allow freedom of movement to be restricted in exceptional circumstances.

"We would have critical new powers that we would unilaterally be able to bring in if we needed to, if a new country joined the EU, for example," Labour MP Lucy Powell told BBC News.

But imposing restrictions on migrants from new EU member states is not a new power. All the existing EU states apart from the UK and Ireland temporarily imposed restrictions on the right to work for citizens of the eight countries that joined the bloc in 2004: the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia.

The UK did the same to Romania and Bulgaria in 2007.

Ms Powell's claim is based on Article 112-114 of the EEA Agreement, external, which says countries can take unilateral action if they are facing "serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties".

The measures have to be taken in consultation with other EEA members, and reviewed every three months.

The only EEA country that has managed to use this is Liechtenstein, which was allowed a restriction on freedom of movement based on it being a very small country, with a population that would only fill about half of Manchester United's Old Trafford stadium.

There is considerable doubt that a country with the size, population and economy of the UK would be able to do the same thing.

What about the European Court of Justice?

Clearly, European Court of Justice (ECJ) rulings on single market matters would still be relevant to the UK, but the court would no longer have direct powers to rule on matters of European law arising in the UK.

Instead, such issues would be heard by the EFTA Court, which has a judge from each of the member countries, so currently it has three judges and presumably if the UK were to join EFTA it would also get to nominate a judge.

The EFTA Court tends to follow ECJ rulings closely.

Also, its rulings are not legally binding on the member states, unlike the ECJ's.

- Published28 March 2019

- Published30 October 2018