How do European elections work?

- Published

The European Union (EU) has agreed a Brexit delay until the end of October and preparations have started to take part in the European elections on 23 May.

Prime Minister Theresa May says if a deal gets through Parliament before that date, the UK will not participate. But it seems likely that the UK will still be in the EU at that point.

What is the European Parliament?

The European Parliament is directly elected by EU voters.

It is responsible, along with the Council of Ministers from member states, for making laws (proposed by the European Commission) and approving budgets.

It also plays a role in the EU's relations with other countries, including those wishing to join the bloc.

Its members represent the interests of different countries and different regions within the EU.

How are its members elected?

Every five years, EU countries go to the polls to elect members of the European Parliament (MEPs).

Each country is allocated a set number of seats, roughly depending on the size of its population. The smallest, Malta (population: around half a million) has six members sitting in the European Parliament while the largest, Germany (population: 82 million) has 96.

At the moment there are 751 MEPs in total and the UK has 73.

Candidates can stand as individuals or they can stand as representatives of one of the UK's political parties.

Once elected, they represent different regions of the country, again according to population. The north-east of England and Northern Ireland have three MEPs each while the south-east of England, including London, has 18.

While most UK MEPs are also members of a national party, once in the European Parliament they sit in one of eight political groups which include MEPs from across the EU who share the same political affiliation.

Member states can run elections to the European Parliament according to their own national laws and traditions, but they must stick to some common rules. MEPs must be elected using a system of proportional representation - so, for example, a party which gains a third of the votes wins a third of the seats.

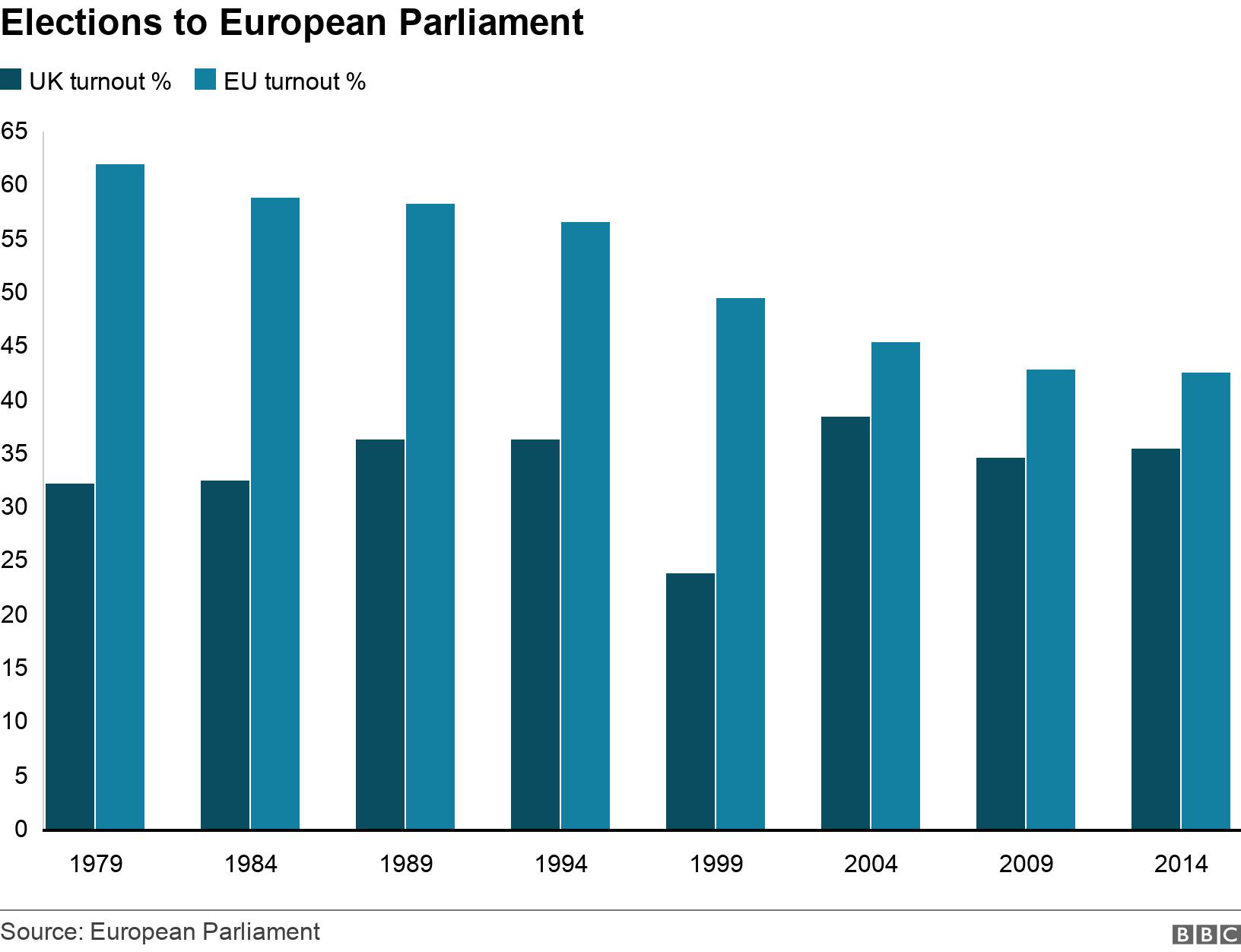

Turnout in the UK for European Parliament elections is low both by EU standards and by the standards of other UK elections.

The last time they were held in 2014, 36% of those eligible to vote did so, compared with 43% in the EU as a whole.

That compares with 66% turnout at the following year's general election.

In 2016, 56% of the electorate voted in the Scottish Parliament elections, 45% in the Welsh Assembly and 54% in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

In local elections in England, turnout varies depending largely on what other elections are taking place on the same day, sometimes dipping as low as the European elections turnout and sometimes rising close to the level of general elections.

How much do elections cost?

The last time European elections were held in 2014, the UK spent £109m on them.

The main costs were running the poll itself (securing polling stations and venues to run counts) and mailing out candidate information and polling cards.

The government has said that if the UK does not end up participating in the 2019 elections, it will reimburse local returning officers - the people responsible for running elections - for any expenses already paid.

What happens if the UK leaves?

The EU is planning to reduce the overall number of seats in the parliament from 751 to 705 when the UK leaves.

There will be a reallocation of 27 of the UK's seats to 14 other member states that are currently underrepresented. And the rest will be set aside with the possibility of being allocated to any new member states that join in the future.

The EU has already passed legislation to do this, but it does not take effect until the UK leaves.

The number of seats is capped in law at 751.

The European Commission had advised that as long as the UK made a decision to take part in the European elections by mid-April, this reallocation would be reversed.

But what if the UK elects MEPs and then passes a deal to leave the EU?

In that case, the UK MEPs would not take their seats, leaving vacancies.

The House of Commons Library says that extra MEPs could potentially be elected on "stand-by" in some member states but not take up their seats until the UK leaves the EU.

- Published28 October 2019