Boris Johnson: What is his Brexit plan?

- Published

Boris Johnson is the UK's new prime minister and will now begin the task of trying to deliver Brexit.

The former foreign secretary has pledged the UK will leave the EU on 31 October, "do or die", accepting that a no-deal Brexit will happen if an agreement cannot be reached by then.

He has called the withdrawal agreement "dead" but says he will "take the bits that are serviceable and get them done" - such as guaranteeing the rights of 3.2 million EU citizens in the UK.

The withdrawal agreement (WA) is the deal negotiated by the UK government and the European Union (EU) to settle the basis on which the UK will leave. As part of it, the UK agreed to pay the EU a "divorce bill" (estimated to be £39bn), guarantee EU citizens' rights and sign up to the Irish backstop - an insurance policy designed to avoid a hard border in Ireland.

The deal allowed for a transition period after Brexit, during which things like UK-EU trade would stay the same, while both sides worked out their future relationship. But the withdrawal agreement was rejected three times by MPs - leading to Theresa May's downfall.

Irish border

Solve the problems of the Irish border where they properly belong, in the context of the free trade agreement, that we will do after we come out on 31 October.

After Brexit, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland could be in different customs and regulatory regimes, which might mean products being checked at the border. To avoid border posts (which some believe could threaten the peace process), Mrs May and the EU agreed on the backstop. In the event that no free trade deal was agreed that avoided a hard border, this insurance policy would effectively keep the UK and EU in a customs union. This proved controversial because it would stop the UK doing some of its own trade deals.

Mr Johnson is saying the Irish border can be dealt with after the UK leaves the EU, instead of as part of the withdrawal agreement.

Obstacle: The EU has said the Irish backstop cannot be removed from the withdrawal agreement - the deal to delay the UK's exit until the end of October specifically prohibited its renegotiation. If the UK leaves with no deal and seeks a free trade agreement, the EU has said it will not begin negotiations until the issue of the Irish border is settled.

Would you notice if you crossed the Irish border? (Video from 2017)

Irish backstop

There are abundant, abundant technical fixes that can be introduced to make sure that you don't have to have checks at the border.

Boris Johnson wants to ditch the Irish backstop - he's called it "a prison". He has said there are "abundant, abundant technical fixes" to avoid checks at the border. He concedes there is "no single magic bullet" but points to a "wealth of solutions" instead.

Obstacle: The UK and the EU have previously looked for technological solutions to the Irish border without success. EU deputy chief negotiator Sabine Weyand said in January: "We looked at every border on this Earth, every border the EU has with a third country - there's simply no way you can do away with checks and controls." There are "alternative arrangements" which could help: trusted trader schemes (where businesses are certified to make sure they meet certain standards) and ways of making customs declarations away from the border, but they wouldn't eliminate the need for checks altogether. After Brexit, the EU would still require inspections of things like animal and plant products entering its single market, and the new entry point to that market would be at the Irish border.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

£39bn

I think that the £39bn should be kept in a state of creative ambiguity.

Boris Johnson has said he is prepared to withhold the money the UK has agreed to pay the EU and use it as a negotiating tool to get a better deal. Settling the UK's financial obligations (which include previously agreed contributions to the EU budget and funding things like EU staff pensions) was agreed by Theresa May as part of the withdrawal agreement. The figure for those obligations has been calculated at £39bn.

Obstacle: The EU has said it will not start future trade talks until the issue of money (along with citizens' rights and the Irish border) is settled. Refusing to pay would almost certainly sour relations between the two, and could lead to a legal challenge from the EU.

No deal

It's vanishingly inexpensive if you prepare.

While accepting that a "disruptive... badly handled" no-deal Brexit would be costly, Mr Johnson said it was "vanishingly inexpensive if you prepare" and added that "much of this work has been done".

Obstacle: Mr Johnson's view of the cost of a no-deal Brexit is at odds with the vast majority of economists, a significant number of his own backbenchers, and organisations such as the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), which calculates the government's forecasts for the economy. The OBR said no deal would push the UK economy into recession.

Zero tariffs

“There will be no tariffs, there will be no quotas, because what we want to do is get a standstill in our current arrangements under GATT24

Mr Johnson has said he would mitigate the effects of no deal on the UK economy (which he admits would cause "disruption") by relying on a piece of trade law known as Article 24. He originally said this would allow the UK and the EU to have zero tariffs (taxes on imports) on trade while the two sides negotiated a trade deal. This would, in theory, help keep trade flowing and would stop the EU imposing tariffs on goods being imported from the UK (cars, for example, are subject to a 10% import tax from non-EU countries, and on agricultural produce it's even higher).

Obstacle: Boris Johnson was wrong to say Article 24 would automatically allow for a standstill in trade relations, and indeed - when challenged in interviews - he later accepted that it would require the agreement of both sides. Also, Article 24 only covers the trade in goods (not services) and it does not cover non-tariff barriers such as regulations. The EU has ruled out signing any Article 24 agreement immediately after a no-deal Brexit.

What is the timetable?

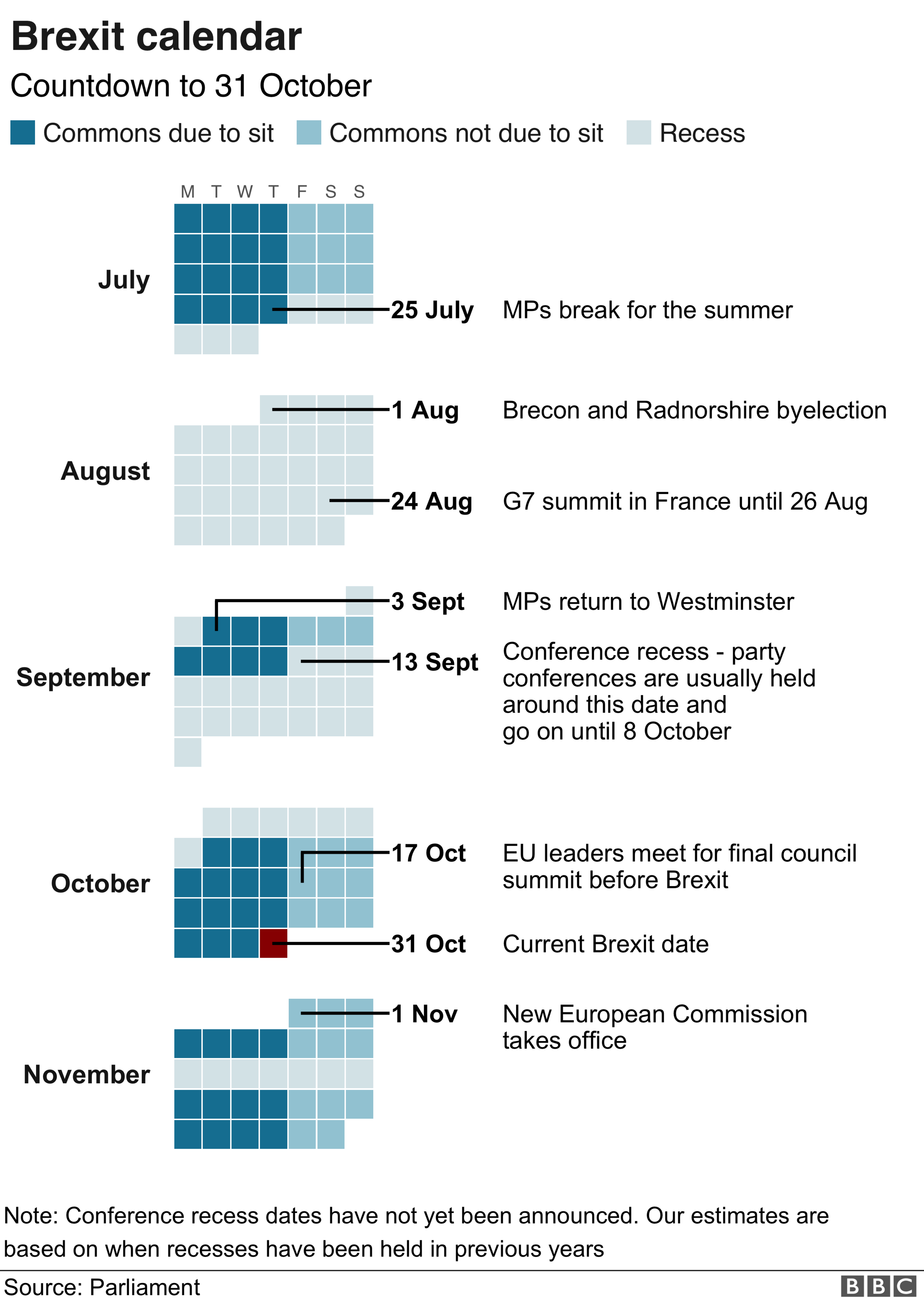

Mr Johnson has just over three months until Brexit day. He will become prime minister on 24 July and Parliament begins its summer recess the following day.

A week later there will be a by-election and the rest of August will be pretty quiet, both in Westminster and Brussels. Parliament returns at the start of September but will take another recess later in the month for party conferences.

On 17 October there will be a summit of EU leaders. Brexit is scheduled for 31 October, the day before the new European Commission takes office.

If you are reading this page on the BBC News app, you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website, external to submit your question on this topic.