Brexit: Does the UK owe the EU £39bn?

- Published

Prime Minister Boris Johnson has told the House of Commons that in the case of a no-deal Brexit: "We would of course have available the £39bn in the withdrawal agreement to help deal with any consequences."

He was referring to the UK's "divorce bill" from the European Union (EU).

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn asked Mr Johnson if he would "acknowledge that the £39bn is now £33bn".

Mr Corbyn is right - the latest estimate from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), external says that, as a result of the delay to the Brexit date, a chunk of the money has already been paid, and that the current bill would be about £33bn.

What is the "divorce bill"?

This is the money the UK agreed to pay the EU after leaving.

Officially it is called the financial settlement (unofficially, the "divorce bill") and was negotiated as part of Mrs May's withdrawal agreement, external.

The withdrawal agreement was the deal that would have seen the UK leave the EU on 29 March, and then enter a transition period until 31 December 2020.

During this period, the UK-EU trading relationship would have stayed the same - allowing both sides to try to sort out a future trade deal.

Although no longer an EU member, the UK would have paid into the EU budget as it does now (and receive funding back).

But the deal was rejected three times by MPs at Westminster and Brexit was delayed until 31 October.

How much is it?

The withdrawal agreement (agreed in November 2018) set out calculations, rather than a figure, for how much the UK would need to pay to settle all of its obligations.

That is why there has not been an official figure for it. The OBR estimated it would be £38bn, while the government had said between £35bn and £39bn.

The biggest part of the bill was the UK contributions to the 2019 and 2020 EU budgets. The UK puts about £9bn a year into the budget, once you have deducted the rebate and money returned to the UK to be spent on public sector projects.

As Brexit was delayed from 29 March to 31 October, some of that money has been paid as part of the UK's normal membership contributions, which means it is no longer part of the "divorce bill". The OBR estimates that the bill is now £33bn.

What is the money for?

Some of the rest of the payment would come from contributions towards EU budget commitments made while the UK was still a member of the EU, which have not yet been paid.

The UK would also contribute towards EU staff pensions incurred before Brexit.

The UK would receive some money back: the £3bn of capital it had paid into the European Investment Bank, as well as a small amount of capital paid into the European Central Bank.

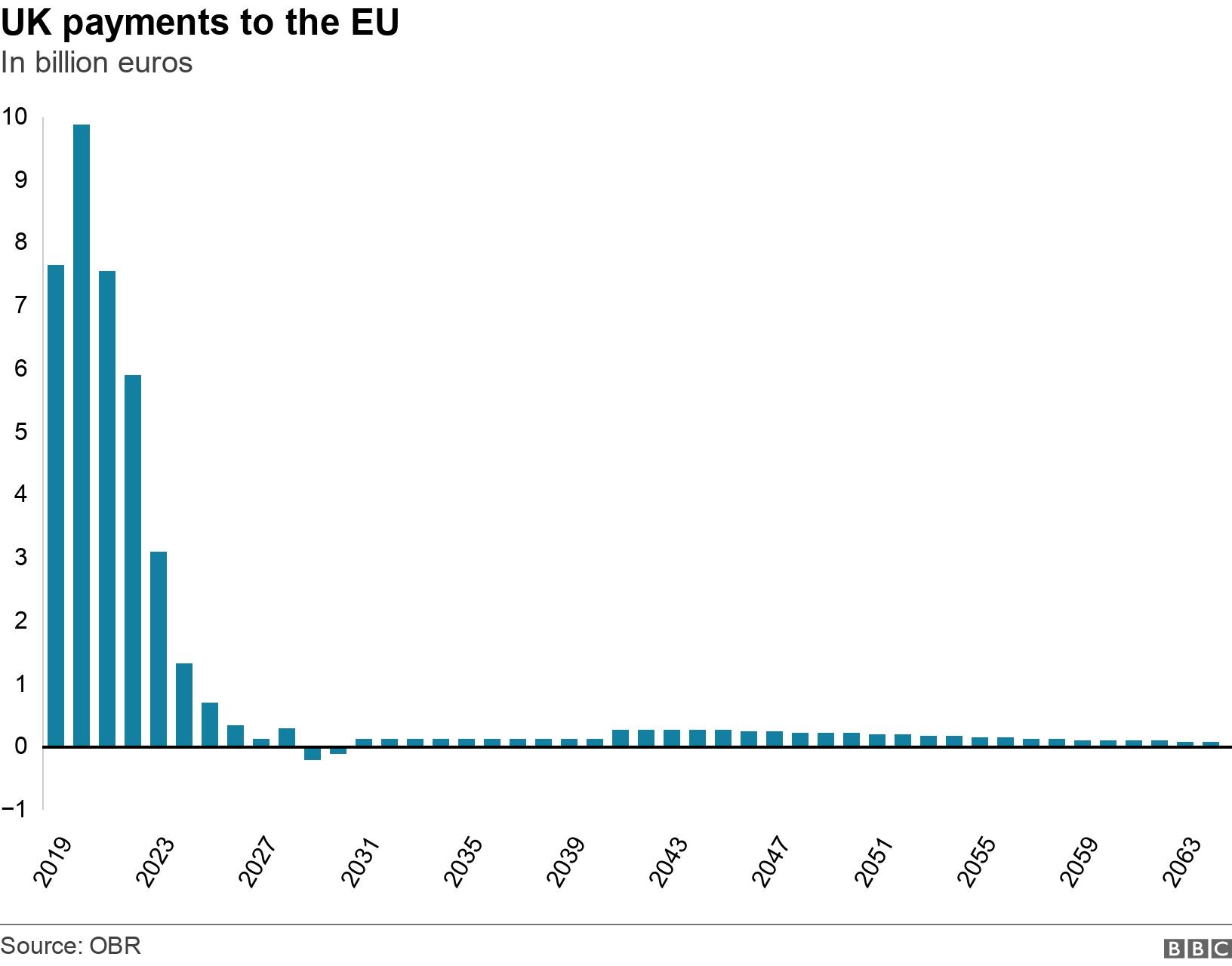

The OBR expects that most of the money - around three-quarters of the total - would be paid by 2022, with some relatively small payments still being made in the 2060s.

Can the UK withhold the money?

Mr Johnson has suggested withholding the money - using it as a bargaining chip in future negotiations with the EU, or injecting it into the UK economy to try to avert the effects of a no-deal Brexit.

This could have legal and other consequences.

The Institute for Government think tank says refusing to pay could lead to a legal challenge. It says: "The EU might seek redress through the International Court of Justice or the Permanent Court of Arbitration, both located in The Hague."

But a House of Lords report into Brexit and the EU budget, published in 2017,, external stated: "While the legal advice we have received differed, the stronger argument suggests that the UK will not be strictly obliged, as a matter of law, to render any payments at all after leaving."

Catherine Barnard, professor of EU law at University of Cambridge, says that because such a situation has never arisen before, "no-one is quite sure what might happen".

When it comes to future talks with the EU - such as negotiating a free trade agreement - withholding the money would sour relations.

The EU has said consistently that it will only begin trade negotiations once the issue of financial obligations, citizens' rights and the Irish border have been resolved.

- Published23 July 2019

- Published18 November 2016