Modern slavery: What has Theresa May done to tackle it?

- Published

As one of her last acts as prime minister, Theresa May is promising money to help end modern slavery, something she has described as the "great human rights issue of our time".

It became a focus of hers during her time as home secretary, as she sought to highlight the more than 10,000 people in the UK estimated to be living in domestic servitude, labour exploitation or having been trafficked for sex.

Others have put the figure much higher.

The Modern Slavery Act 2015, introduced by Mrs May before she became prime minister, brought together existing offences into one law. It also created new duties and powers to protect victims and prosecute offenders.

It introduced a new defence for victims of slavery and trafficking who have been forced to break the law.

It gave the police more power to stop boats where trafficking is suspected, and the courts the power to hand down a maximum life sentence for offenders or to place restrictions on people they believe may commit a human trafficking or slavery offence.

It also required businesses with an annual turnover of at least £36m to publish an annual statement setting out the steps, if any, they have taken to prevent modern slavery within their supply chains.

And the law created an anti-slavery commissioner to oversee this, a post currently held by former head of the National Police Chiefs Council Sara Thornton.

How successful has it been?

There has been a considerable increase in tackling modern slavery offences at every stage since the law was introduced. The police are referring more cases to be prosecuted, the Crown Prosecution Service is making more decisions to charge, and there are more convictions.

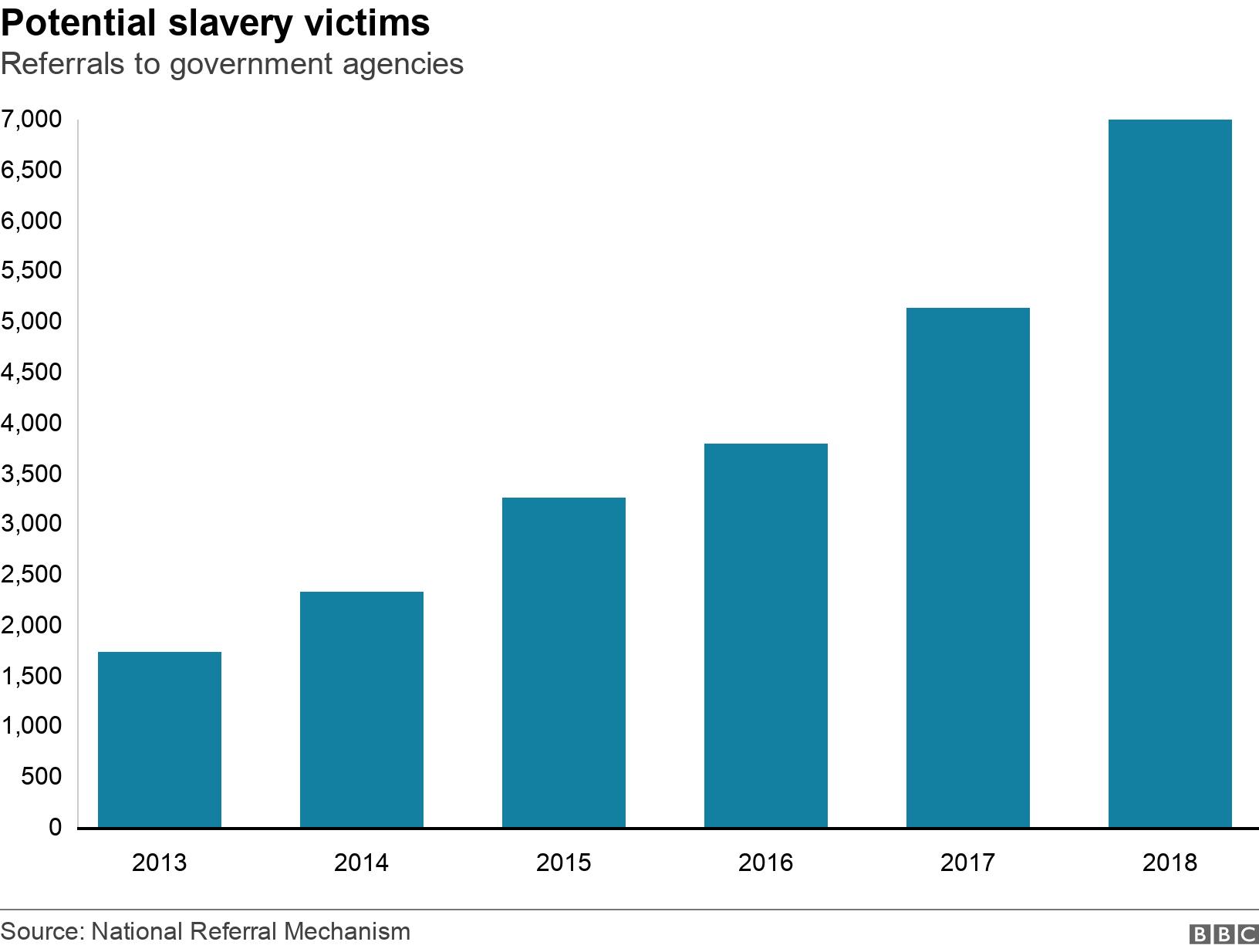

Referrals to the UK's system for identifying and supporting victims of trafficking, the National Referral Mechanism, have increased year-on-year since it was created in 2009.

In 2018, it received 6,993 referrals of potential victims, including six suspected cases of organ harvesting. The most commonly claimed types of crime were labour exploitation of an adult and domestic servitude of a child, followed by sexual exploitation.

This was an increase of more than a third on the year before when there were 5,142 reports - which itself represented an increase of more than a third on the year before that.

The government's annual report on modern slavery for 2018 said this was likely to be down to increased awareness of the crime and increased police activity to tackle it. It did acknowledge some of this may be due to an increase in the crime itself, though.

The National Crime Agency says: "Although it is impossible to know exact numbers of victims, we do know that modern slavery has been on the increase."

In the year to March 2018, police across the UK recorded 3,428 modern slavery crimes, about a 50% increase on the year before.

This translated to an increase in people being charged in the courts. In 2017-18, 239 suspects were charged with modern slavery offences, up 27% on the year before, according to the Crown Prosecution Service, from 188 to 239.

An increase in prosecutions and convictions began before the law was introduced.

When the law was first introduced, although there were more convictions overall, the conviction rate fell - more people were being charged with a crime but the number of successful prosecutions didn't keep up.

This gap has started to close and last year the conviction rate was 65% - up from 61% the year before.

What are the concerns?

An independent review was positive about the intent of the modern slavery law, describing it as "an innovative piece of legislation that has influenced parliaments across the world".

But it pointed out that the section targeting businesses has had limited impact because of a lack of enforcement or consequences.

There are no direct penalties for not complying with the law.

And there is a loophole allowing businesses to produce statements saying they have taken no steps to address modern slavery in their supply chains and still be compliant with the legislation.

Another, perhaps more fundamental, concern arises when efforts to protect victims of modern slavery come into conflict with another of Mrs May's main focuses during her tenure as home secretary - immigration.

Theresa May worked with the UN on international goals on tackling slavery

Once someone has been confirmed to be a victim of slavery, their nationality and immigration status can affect both what support they receive while their case is being processed, and what happens to them afterwards.

In the first three months of this year, 70% of potential victims referred to the authorities were not British nationals.

A select committee inquiry into modern slavery in 2017 said that having escaped from slavery in the UK, victims were treated differently from refugees fleeing ill-treatment overseas.

"While recognition as a refugee grants an initial period of five years' leave-to-remain in the UK, recognition as a victim of slavery... confers no equivalent right-to-remain, for any period," the report said.

This means victims can face deportation, "destitution or even a return to their enslavers because they have no ongoing access to support".

Both the select committee report, and the independent review published this year, recommended reforms.