How often do ministers change jobs?

- Published

Boris Johnson with the current cabinet. The cabinet secretary is sitting on his right.

Ministerial resignations (often over Brexit) became so commonplace in the past couple of years you could be forgiven for starting to think they were not that big a deal.

But ministers run government departments - and regular changes of direction are challenging, according to Lord O'Donnell, who was cabinet secretary, the head of the civil service, between 2005 and 2011.

"When David Cameron asked me in 2010 what he could do for me, I told him my number-one priority would be to keep ministers in post for as long as possible," he told BBC Reality Check.

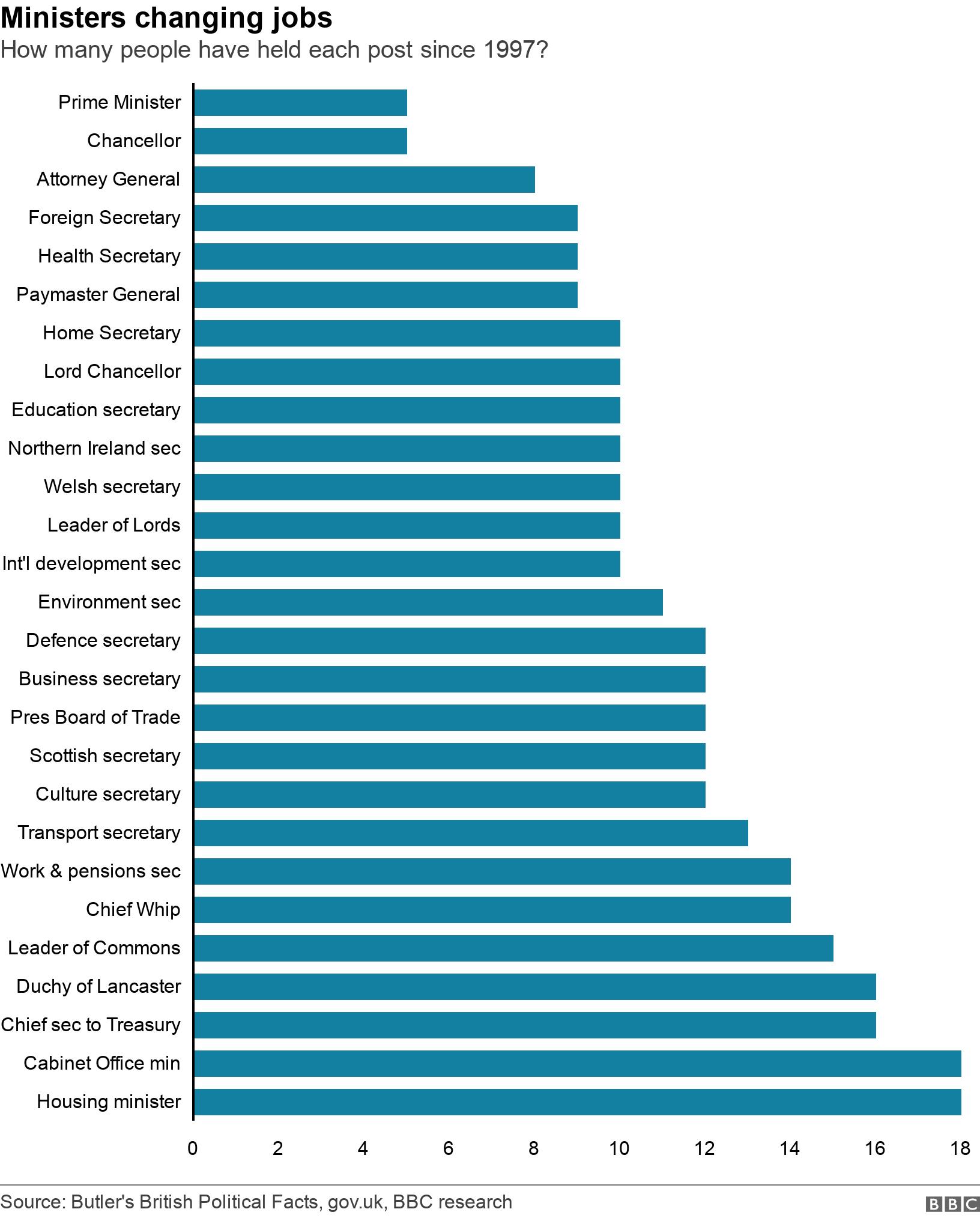

To see why he was concerned, we looked back at how many people had held cabinet posts since 1997 - we decided to look at the jobs of all the ministers who currently attend cabinet meetings.

Not all of those posts have existed since 1997, as prime ministers have changed departments and created new ones.

There was no secretary of state for exiting the European Union or secretary of state for justice in 1997, for example, and there was no paymaster general between 2007 and 2009.

There are many jobs that have clearly been continuous since 1997 though.

In that time, we have had five prime ministers and five chancellors of the exchequer.

At the other end of the scale, there have been 18 ministers with responsibility for housing and 18 Cabinet Office ministers.

Hilary Armstrong was the first housing minister under Tony Blair and was followed by Nick Raynsford, who said the number of housing ministers had been a problem.

"Successful housing policies require long-term investment and continuity," he told Reality Check.

"If ministers think they are only going to be in post for a few months, they will inevitably only focus on short-term initiatives, which may earn them a good headline but are unlikely to to deliver substantial and lasting benefits."

Meanwhile, organisations concerned with housing complain they constantly find themselves rebuilding relationships, while targets for new houses have been missed and the need for new affordable and social housing has not been met.

Christine Whitehead, professor of housing economics at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), gave an example of the problems of fast turnover from the time of the Grenfell Tower fire, on 14 June 2017.

"The previous minister had been moved on 9 June and Alok Sharma took over on the day of the fire," she said.

"All other housing issues were completely forgotten as he concentrated on the aftermath and putting in place the social-housing Green Paper - but he was moved on in January 2018, before any effective policy ideas could be put in place."

Martin Wheatley, from the Institute for Government (IFG), said this kind of rapid turnover meant housing policy tended not to be decided in the housing department at all.

"The combination of the political salience of housing and the high turnover of secretaries of state and ministers in the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government and its predecessors, tends to mean that policy is prone to end up largely being steered by the Treasury and 10 Downing Street," he said.

Ministerial churn

There have been extreme examples of ministers being in jobs for short periods.

David Laws was chief secretary to the Treasury for just over two weeks in 2010 before he resigned over his expenses claims.

Andrew Mitchell's tenure as chief whip lasted from 3 September until 19 October 2012, when he resigned over an argument with police officers in Downing Street.

In just over a decade, Margaret Beckett was business secretary, leader of the House of Commons, environment secretary, foreign secretary and housing minister

And we're not even counting Greg Clark, who was accidentally appointed president of the Board of Trade for four days in Theresa May's government in 2016.

There were 40 ministerial resignations from Mrs May's government before July 2019, a rate of departure unmatched even in the later days of Margaret Thatcher, for which Prof Jessica Adolino, from James Madison University, blamed, external Mrs May's attempt to balance her cabinet between leavers and remainers.

Laura Kuenssberg: May was just overwhelmed by the job

At the other end of the scale, Prime Minister Tony Blair and his Chancellor, Gordon Brown, spent just over 10 years in post, while Dawn Primarolo was paymaster general for more than eight years and Tessa Jowell was in charge at Culture Media and Sport for six years.

And in 2010, when Lord O'Donnell asked David Cameron to keep ministers in post for as long as possible, his wish was granted.

"The coalition government had the unexpected side-effect of raising ministerial tenure," he said.

"Because it was harder to find Lib Dem ministers, we did everything to avoid moving the key players."

Helen Liddell was transport minister for just two months, in 1999, before being moved to trade and industry

While there had been eight work and pensions secretaries between 1997 and 2010, there was only one in the following six years - and another five in the following three years.

The IFG has long been campaigning for less churn among ministers, partly blaming it for the constant upheaval in further education policy, which has seen five major reorganisations in the past 20 years and a succession of institutions, such as the Quality Improvement Agency and the Learning and Skills Improvement Service, it says have not been given long enough to prove their worth.

Much of the churn in ministers is because of how and why they are appointed, according to Andrew Turnbull, who was cabinet secretary from 2002 to 2005.

"Ministers get appointed to new jobs not on the basis of how good they are at doing their current job - it's more about visibility. Being good at media work is crucial as is having lots of eye-catching initiatives," he said.

"It's a dysfunctional system but it's there because politics is a competitive game and control of promotions is a key source of power for prime ministers."

But, he added: "Tony Blair eventually realised that each time he promoted someone, he had to push someone out, which meant that by the end of a parliament the backbenchers were increasingly disaffected."

And there has been even more turnover in junior roles, which the IFG has also criticised, external, as certain posts can be seen merely as a career stepping stone.

In one of the great exchanges in 1980s BBC political sitcom Yes Minister, two senior civil servants explain why it is right for them to stay in their jobs for much longer than ministers.

"Power goes with permanence," they say, "impermanence is impotence," before concluding it was high time the ministers "all had a little spin".