Reality Check: Do we really know the scale of UK migration?

- Published

Estimates suggest 630,000 immigrated to the UK last year, but how accurate is that number?

Latest figures show that net migration from the European Union is at its lowest level since 2012 - but how are the numbers gathered, and how reliable are they?

The system the UK used to use to estimate long-term migration was, in the words of the Office for National Statistics, "stretched beyond its purpose".

The system's critics have been a little harsher. They say it offers at best an educated guess - and at worst is deeply flawed.

Every three months the Office for National Statistics (ONS) publishes a migration update. And at the heart of that report is the International Passenger Survey, external (IPS).

This enormous exercise was launched in 1961 to help the government better understand the impact of travel and tourism on the economy - but over the years, it became a rather useful way of estimating who was coming and going for broader political purposes.

When the David Cameron government set a net migration target of tens of thousands in 2010, the IPS projection became a very public measure of policy failure.

So how does the IPS come up with its figures, and why is it so controversial?

Limits to the Passenger Survey

For 362 days a year, IPS staff leap in front of travellers at 19 airports, eight ports and the Channel Tunnel rail link. They ask them for a bit of their life story: where they're from, why they're in the UK and how long they might be staying.

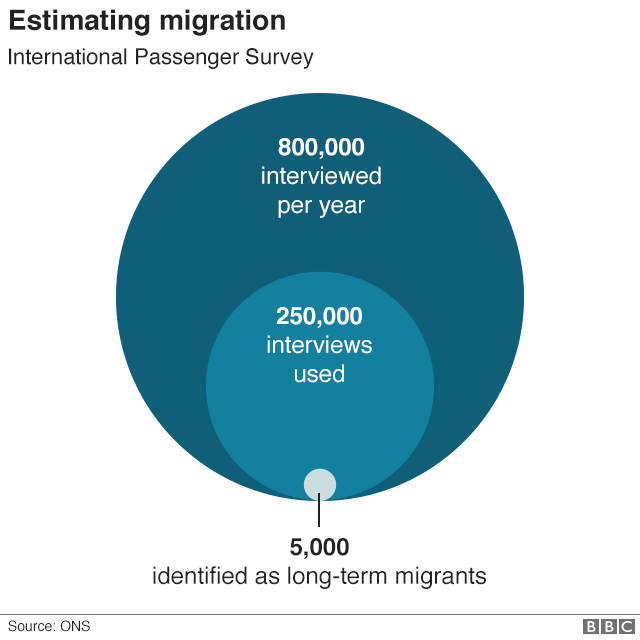

Up to 800,000 people a year take part and about 250,000 of those results are put through the statistical mixer to come up with an estimate for the number of people either arriving to live in the UK, or leaving the UK for at least a year - the internationally-agreed definition of a long-term migrant.

But the IPS doesn't cover all the ports, all of the time. Take Dover, for example. There are up to 51 ferry arrivals a day - and the IPS only covers four days' worth of them over an entire year. The nationwide sample works out at just over 1% of Heathrow's annual traffic of 78 million people.

Within the sample, the number of known migrants is about 5,000. So they are an incredibly small group, within an already small sample, upon which statisticians are expected to give ministers some big answers.

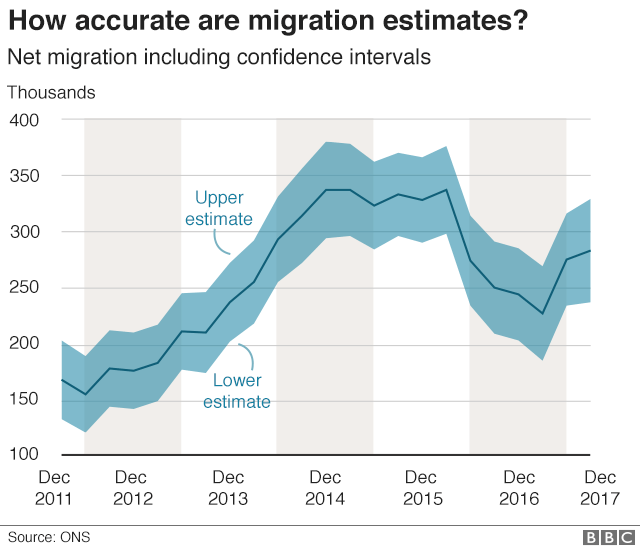

The ONS publishes figures that, in layman's terms, show how confident it is in the estimates.

Here's how it works. Last July the ONS estimated net migration to be 282,000 a year. But there is a large margin of error. The figure could be wrong by 47,000 either way. So net migration could be as low as 235,000 or as high as 329,000.

That is the statistical problem with surveys the world over. And two parliamentary committees in just over a year have concluded that the IPS is now next to useless, on its own, for what ministers need it to do.

In 2015, a gap between the number of international students arriving and leaving prompted accusations that a lot of students were illegally over-staying their visas.

"The fact is too many [students] are not returning home as soon as their visas run out," Theresa May told that year's Conservative Party conference. "I don't care what the university lobbyists say. The rules must be enforced. Students, yes; overstayers, no."

It turned out there was no mass over-staying. The first ever experimental deep dive into departure gate data (more on that in a moment) revealed 97% of students went home on time. The gap was all down to the limitations in the IPS.

Last year the Lords' Economic Affairs Committee, external was more scathing still, saying the statistics were so poor that ministries were "formulating policy in the dark".

Using new data

Earlier this year, the ONS says,, external it began to use other data sources in its migration estimates. These new sources include Home Office administrative data and National Insurance numbers. "Taken together", the ONS says, these "provide a better indication of trends that any single source alone".

National Insurance numbers can be used to count foreign nationals - but having a number doesn't prove someone is in the country. People don't cancel them when they leave.

Then there is Home Office entry clearance data - the official data from visa applications. That's helpful for most of the world - but it doesn't count EU nationals or British nationals who have been living overseas.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) captures the nationality of people working in the UK. But it doesn't capture people in communal accommodation and doesn't cover short-term migration. And there have been claims that the LFS has been undercounting migrants in specific sectors, such as hospitality.

Visa data can be used to measure migration, but not for EU citizens who have visa-free access to the UK

What about the UK census? It's the most definite physical count of people we have - so reliable in fact, that the 2011 exercise added almost 350,000 to the net migration estimates for the previous decade.

But it's a mammoth undertaking, costing close to £500m. And given it only happens once a decade, it's not going to tell you much in an age of mass and rapid migration.

What do other nations do ?

A lot of the UK's peers are more advanced in how they come up with migrant counts. New Zealand makes travellers fill in entry and exit cards - including their own nationals - which gives a precise measure of who's where. You can't get in or out of the country until you fill in the card. The UK had a similar system until it was scrapped in the 1990s.

Many countries have population registers. Italy, for example, requires migrants to register with their local authority.

The big problem with a register? People forget to remove themselves from the list if they move on.

Ways to measure migration:

Passenger survey: interviewing people at borders, but sample sizes can produce large confidence intervals. Used in the UK and Malta.

Visas: the number of people applying for visas to a country, but this does not count those with visa-free travel, such as citizens of the EU. Used in New Zealand, Australia, Canada.

Register: making all new migrants to an area register with a municipal hall. But some people don't do it or simply forget to say when they move on. Used in most EU countries.

Census: almost all countries do this, but it is expensive, so done at long intervals.

The Danes and the Swedes try to resolve that by matching registers with other official sources - and it's this use of "administration data" which is now seen as the holy grail of understanding migration.

The UK's long, long delayed electronic replacement for exit and entry checks is now operational - although the immigration watchdog recently found the Home Office guilty of "wishful thinking" in suggesting it was delivering all it was claimed to do.

The prize for statisticians is to take this kind of data and mash it up with new sources, such as those already being used in Denmark and Sweden.

And that's now the official plan in the UK.

Denmark and Sweden are both seen as countries with better ways to capture migration

In the autumn, the Office for National Statistics will publish its first thoughts on how a new far more reliable count of migrants could work. In an ideal world, it would link the movement of real people to tax records and information about their whereabouts from other sources, such as registrations with schools and GP surgeries.

Such an approach could give us accurate information on both short-term and "circular" migration - people who come and go a number of times.

If this system could be made to work, the International Passenger Survey would no longer be the primary source upon which so much policy - and political hot air - is based.

We would finally have some accurate numbers which could properly capture migration to and from Britain - information which will be critical if control of immigration remains vitally important to voters after Brexit.

Correction: This piece has been amended to reflect recent changes in how the ONS uses other data to draw up migration estimates.

- Published30 July 2018

- Published2 May 2018

- Published16 July 2018