How to win the private members' bill battle

- Published

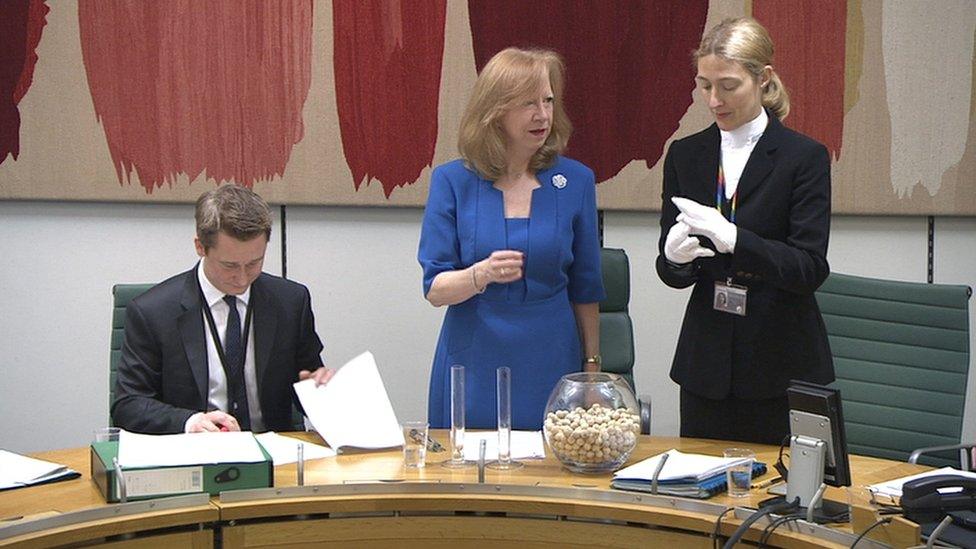

Deputy Speaker Eleanor Laing drew the ballot

A new Parliamentary year means a new set of private members' bills, and the ballot (more like a prize draw, really) which gives 20 MPs a chance to bring in a bill has been revealed.

What they're really winning is debating time - any MP can introduce a bill anytime they like.

But the magic ingredient for success is the allocation of time for a second reading debate, the debate in which MPs are invited to approve a measure in principle and send it off for detailed scrutiny.

In top place this time is Labour's Mike Amesbury, followed by Labour MPs Darren Jones and Anna McMorran.

The highest place Conservative is newcomer Laura Trott, followed by another new Tory, Chris Loader, and Paula Barker from Labour's new intake. Seventh is a relative veteran, the former health minister, Philip Dunne.

These top seven MPs are guaranteed a debate - they get the opening slot in one of seven sitting Fridays in the Commons, which will be reserved for second readings of private members' bills.

Labour MP Mike Amesbury has come first in the ballot but there's no indication yet what his bill will deal with

Those further down the list can claim second place on the Order Paper for those days, but the sting in the tail is that, if the debate on the first bill rambles on too long, they may not be reached at all, and then they go to the back of the queue for priority…

So a key problem for MPs later in the list is to gauge which bills ahead of them on a particular day might go long, and crowd them out of debating time.

Remember that the preferred method of killing off private members bills is "talking out," using up the available debating time, by droning on interminably, and so preventing the bill being put to a vote.

So if the top bill on the agenda is one that will attract the attentions of filibusterers, try to avoid being the next bill on that day's list; you won't get enough time to make progress.

Some private members' bills are pretty uncontroversial - the Conservative Wendy Morton had a bill to ensure Great Ormond St Hospital continued to enjoy the royalties from JM Barrie's Peter Pan in perpetuity.

Others will attract determined opposition - assisted dying, legalisation of cannabis or votes at 16.

So the winning MPs will have to choose between safe subjects that will allow them to get a law onto the statute book, and controversial measures that will require solid support and tactical streetsmarts to succeed.

Like folk in ancient times making a sacrifice to placate the dark powers, MPs with a bill that might attract opposition from those who regard most private members' bills as vexatious flabby nonsense are well advised to try and persuade those sceptics not to block their proposal.

That might entail making concessions or simply explaining their case - but it is foolish not to try and defuse the likes of Conservatives Sir Christopher Chope and Philip Davies at an early stage.

Otherwise they may need to persuade a hundred or more colleagues to make the supreme sacrifice of attending the Commons on a Friday, to vote through a "closure motion" which would force their bill to a vote on its second reading - and if won, get it past that dangerous first parliamentary hurdle.

Plenty more obstacles will then lie in wait - a deluge of amendments when the bill returns from committee consideration, for its report stage, and then the vagaries of the Lords private members bill process. But most controversial private members' bills are killed off in their infancy, unless their promoters are very smart.

Already the phones of the winning MPs in the latest ballot will be ringing incessantly. Pressure groups like Macmillan, the Taxpayers' Alliance and the homelessness charity St Mungo's are already contacting them to offer up their own reform proposals - suddenly they are very popular.

It is completely up to the winning MP to decide what they want to do with this opportunity; but it is an important chance to win friends, impress influential people, and make a name for themselves, as well as a bit of actual law.