Brexit: Will it be a Canadian or an Australian ending?

- Published

A large Commons majority will make it easier for the PM to withstand the inevitable trade-offs ahead

First "Brexit meant Brexit". Then it was the "exact same benefits". Then it was "frictionless trade".

Then it was a reluctant acknowledgement that to get a deal done with the EU, there would have to be some friction, some customs checks, but the promise was they would be minimal.

And never fear, there was still the claim during the election that there was "absolutely zero" chance of failing to get a trade deal by the end of the year, that would guard against some of the risks of leaving the EU.

Now today, as the prime minister acknowledged, "we have made a choice".

With a thumping majority in his back pocket, he wants a Canada-style deal with the EU, a free trade agreement where the two sides - after many years - agree not to charge taxes on imports or to restrict the amount of business that can be done. And, oh, he wants it wrapped up by the end of the year.

It is a significant understatement to say that the Tory Party has been on a journey when it comes to what it wants in the long term from Brexit for how we trade with the EU.

Theresa May was accused by her former chief of staff, Nick Timothy, as always seeing Brexit as a damage limitation exercise.

Whether that's fair or not, it is certainly the case that for the first couple of years after the referendum, the government's agony was largely because the then prime minister was on a quest to avoid too much disruption and it drove Brexiteers round the twist.

But Boris Johnson's team are looking through the other end of the kaleidoscope.

They seem to prioritise the potential, if uncertain, wins of Brexit over protecting against the guessable losses. The ability to do things differently is, for them, the point of having left. And that's why, at the moment, the prime minister is adamant the UK, newly sovereign at the end of this year, simply would not contemplate letting anyone else tell the country what to do.

Australia has been negotiating with the EU for 18 months - while the UK wants its deal wrapped up in less than a year

This philosophy, which was absolutely obvious during the election, smacks headlong though into the EU's opening gambit in these vital trade talks.

It's simple from their point of view as well. The further the UK tacks away from the EU the more complicated it will be to do business, and the less willing they will be to preserve access to their vast market.

Even though Boris Johnson suggested it was outrageous to imagine that the UK was behind the rest of the EU on standards, Brussels does worry about the UK undercutting their businesses, becoming a more nimble competitor ready to grab billions from across the Channel.

So if they're to play nice in terms of doing a deal, they want the government to give legal guarantees that they will stick to the letter of EU rules. If Boris Johnson sticks and says 'no', they might say 'non' to a deal altogether.

Of course there is lots of hard bargaining ahead. The kind of deal that is reached or not reached could have an impact on millions of jobs here and across the continent and billions of pounds of business. And yes, it is in both sides' interests to get a deal done (you'll have heard that before).

But gone today was Boris Johnson's previous breezy optimism about there being "zero chance" of there being no deal by the end of the year. In its place a new claim that if there is no "Canada" deal, there could instead be an "Australian" deal.

Let's be clear about one thing. There is no Australian free trade deal with the EU. Negotiations started on one last year, and at the moment the two sides trade under a decade old much looser partnership while trying to thrash through issues from fuel emissions to what producers on opposite sides of the world should be allowed to call their cheese.

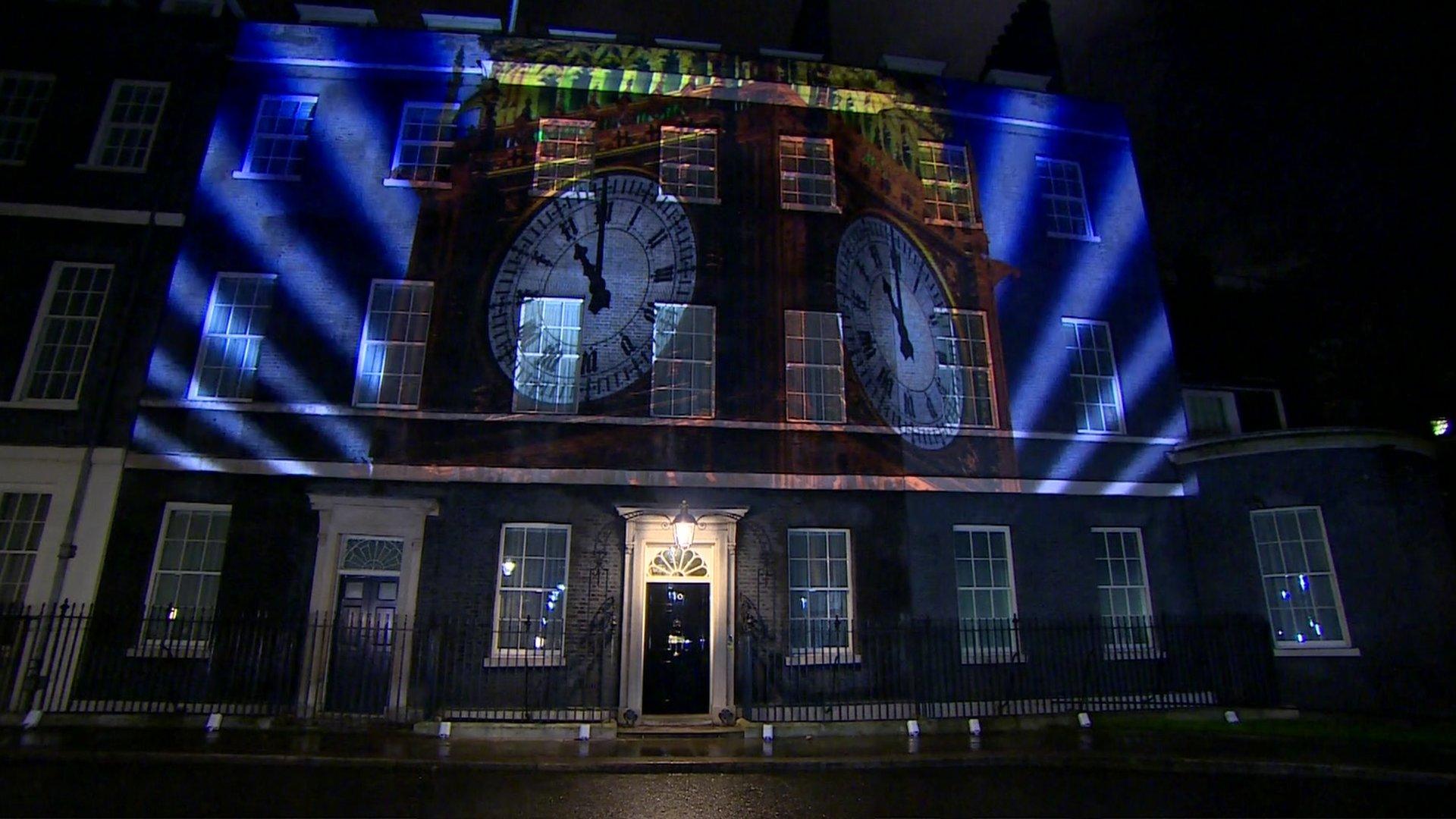

And for Number 10, this sudden reference to an "Australian deal" seems to be an effort to rebrand what the government's written statement later said was a relationship "based simply on the Withdrawal Agreement deal agreed in October 2019, including the Protocol in Ireland/Northern Ireland".

In other words, if there isn't a comprehensive trade deal by the end of the year, the UK would move to a situation trading with the EU on World Trade Organisation terms. This would mean taxes on exports and customs checks which, if it came to pass, could be massively disruptive for businesses and very costly for the economy.

An "Australia-style deal" sounds a lot less scary than the "no deal" circumstance that politicians have talked about for so long. And yes, the issues on paying the EU bill, citizens' rights and the Irish border were all settled in the last few years and the overall divorce deal agreed before our departure last week.

But when it comes to the trade arrangements, it is not the case that as one government official tried to suggest "no deal is not a concept" .

There is no substantial agreement on how the UK will do business with the EU in the years to come. It will take time. There will be big political rows ahead. Right now it seems like the two sides are very far apart.

But don't expect either Number 10 or the EU negotiating team to be particularly rattled by the tough talking by their opponents across the table. It's not surprising that there is a certain amount of chest beating going on. It will be a while before the talks properly begin.

And the EU cannot, this time around, accuse the UK of not being clear about what it wants. That common claim was made repeatedly during the early stages of Theresa May's negotiation. That can't be made this time. There is an obvious approach and a tight deadline.

And however definitive the prime minister was today, the Tories' approach to the kind of deal they will ultimately strike may have more evolutions yet.

With a majority of 80, Mr Johnson doesn't have to worry, like his predecessor, about being able to cope with trade-offs. But he'll be all too aware that the kind of deal he can do, and how long it takes to do it, will be a big factor in defining his political success or failure.

P.S. One former minister suggests waspishly that by suggesting we could leave with a relationship just based on the Withdrawal Agreement, that the government has already got its capitulation in early. Under their interpretation, just basing it on the Withdrawal Agreement would mean prolonging the status quo of the transition period, where we pay into the budget and follow the EU rules.

This, of course, is the opposite to what the government says it is after. But these trade talks will go through many, many machinations and on both sides, smoke and mirrors may apply!

- Published1 February 2020

- Published1 February 2020