Coronavirus: How to help kids cope with life without school

- Published

Children across the UK will be off school for an indefinite period of time because of coronavirus. Some are likely to be anxious, so how can parents help them cope?

No school for the "foreseeable" future. Exams off. Clubs closed.

Millions of children will be looking forward to a spring, and possibly a summer, free of responsibility and routine. But these are not normal times - they're likely to have to spend days and nights indoors with parents or guardians.

They won't get much personal contact with friends and, for teenagers, the cancellation of exams will make a difficult time of year even more worrying.

"It's the perfect storm for parents and children," says Sam Cartwright-Hatton, professor of clinical child psychology at the University of Sussex.

"It's not just the fact that they're going to be cooped up together. Emotions are also going to be super-stressed because - on top of what young people are feeling - parents are worried about jobs, food supplies, paying the next mortgage bill."

Consistent routine

As households begin this forced experiment in enclosed living, Prof Cartwright-Hatton advocates setting a clear routine, particularly for younger children - such as a couple of hours of school work in the morning or a specified time for craft work in the afternoon.

She argues that pre-teenage children "turn inwards quite quickly" if they spend too much time alone.

Parents should play with them and encourage those of an adventurous nature to regard the situation as an "adventure". This approach won't work for the more sensitive children who will need extra reassurance.

Prof Cartwright-Hatton recommends keeping classmates and members of clubs like Brownies, football teams and music groups in touch via Skype, FaceTime, Zoom or other video-conferencing services. This would allow them to share details of their day and play games.

"I would worry about a child who had no-one to play with for six months. We're going to have to get creative in keeping children connected to their peer groups. Kerplunk won't work on Skype, but Cluedo or Monopoly might."

Get out, if you can

Going out won't be as easy as it usually is, which could add to a feeling of claustrophobia as spring and summer approach. Those with gardens are encouraged to use them for fresh air and exercise.

"A balance has to be struck between mental and physical health, depending on what the next piece of official information is," says Eva Lloyd OBE, professor of early childhood at the University of East London.

"If it's safe to go the park, people should do that too."

Limit the doom and gloom

It's impossible to shield all but the youngest children from coronavirus talk, particularly with parents turning on TVs at 17:00 GMT for the latest government briefing.

But Prof Cartwright-Hatton suggests not exposing under-10s to any news at all, except in tailored forms such as the BBC's Newsround, which consults experts on its likely psychological impact.

Teenagers are better equipped to make their own judgements, but they should not be left in their rooms for hours on end searching the internet or using social media unsupervised, she warns.

LIVE COVERAGE: Latest from the BBC

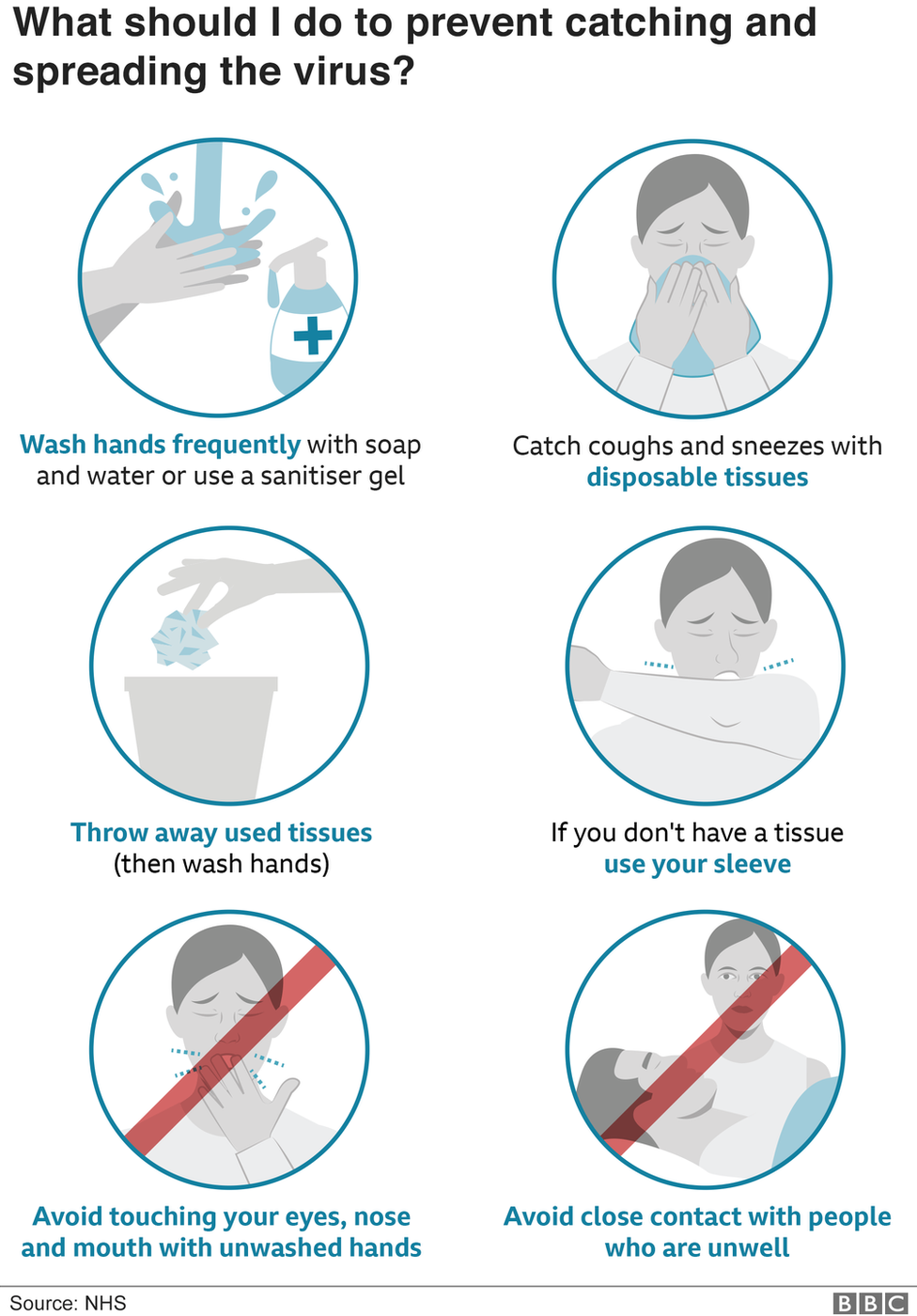

EASY STEPS: How to keep safe

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

GETTING READY: How prepared is the UK?

PUBLIC TRANSPORT: What's the risk?

Another potential outcome of so much information coming children's way - along with a great deal of advice, such as standing two metres away from grandparents to avoid possible transmission - is "guilt", says Prof Lloyd.

"I worry that they'll wonder whether this is happening because of something they've done," she adds. "It's a very strange situation for them. We've got to show them that none of this is their fault and that children throughout the world are going through the same experience."

Coronavirus news is grim for people of all ages, but parents can offer perspective.

"Downplay their fears but be realistic," says Prof Cartwright-Hilton. "Don't promise things that you can't be sure aren't true. If there's misinformation about the number of deaths from coronavirus, you can counter that.

"But, whenever you've discussed coronavirus, move on afterwards, so children don't spend too much time thinking about it."

Exam fears

Students who were due to take their GCSEs, A-levels, Highers and other exams have had them cancelled. They don't know when or if they will go ahead at a future date.

Teenagers who would otherwise be revising could now be at home wondering how they will get their qualifications.

"I'd listen and be very sympathetic," says Prof Cartwright-Hatton. "Whatever emotions the situation is throwing up, tell them you understand how awful it must be at the moment and what a shame it is.

"But let them know you can't solve this for them. If they are really catastrophising about it - worrying that they won't go to university and won't get a job - correct that, because it's not the case."

Be prepared to change

The situation the UK finds itself in is new for parents and children.

Prof Lloyd says families should hold a "review" at the end of every week to discuss how the arrangement is faring.

"It's going to be challenging," she says. "If it's not working, people will need to change it. We should include the children in discussions. From the age of about two they will want to have an input."

Discussions between parents over their own coronavirus worries can wait until after children have gone to bed, Prof Lloyd adds.

When will it end?

At the best of times, children are inclined to ask: "Are we nearly there yet?" or "Is it nearly over?" Explaining the word "indefinite" might prove problematic.

"For young children that's an emerging concept," says Prof Lloyd. "You get them to imagine the summer holidays, that it would be long like them, but not so much fun."

The upside

It's a daunting prospect for parents, taking over what the state has offered for well over a century - daytime education and childcare. But might there be another way of looking at things to ensure the coming weeks and months are more bearable?

"We often talk about work-life balance and parents not being able to spend enough time with kids," says Prof Cartwright-Hatton. "That's not going to be a problem for a lot of people for quite a while now. We've got to look for the silver lining in all this."