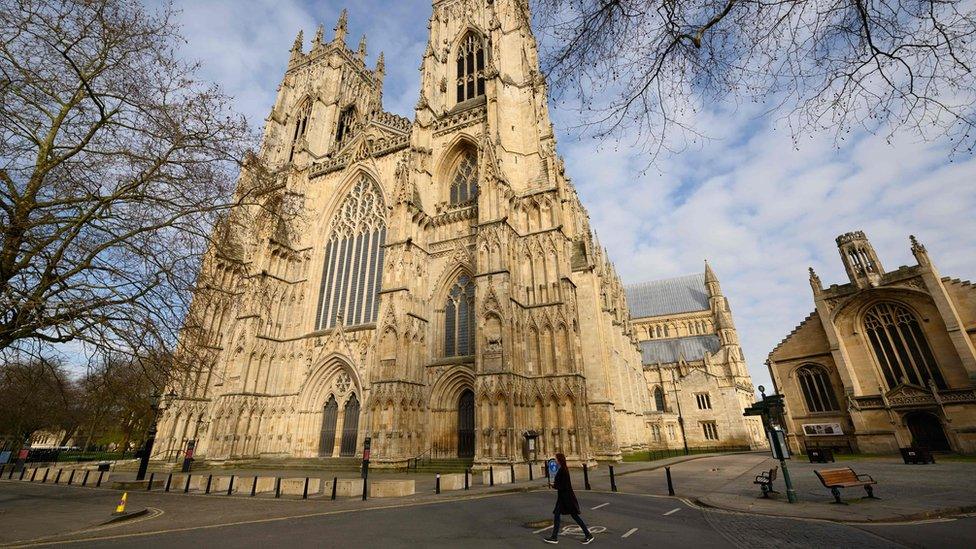

House of Lords: Will the chamber really move to York?

- Published

York here we come?

Might MPs and peers, or maybe just the peers, move to some suitable location in York for several years, while the Victorian home of Parliament is refurbished?

Much depends on how that refurbishment will proceed.

Last year, MPs and Lords agreed they would move out when the work began and legislated to create the Parliamentary Works Sponsor Body, to work up an outline business case (OBC) for R&R, the Restoration and Renewal project, to be agreed by both Houses of Parliament.

The government now wants this decision rethought, which might mean a scaled-down programme focussed on ensuring Parliament does not burn down, or a partial emptying of the building, with some parliamentarians remaining in situ.

The options listed by Boris Johnson in his letter to the Sponsor Body include moving Parliament to nearby buildings, or to York, to sit alongside a new "government hub," for a few years.

Given earlier proposals from Downing Street, this might be a step towards the Lords staying there in the long term.

Or it might not. Boris Johnson has a track record of floating eye-catching ideas - a new "Boris Island" London airport in the Thames Estuary, a garden bridge across the Thames. Is this another example?

All the prime minister's letter really says is that every option is up for grabs, if the place doesn't burn down first.

Could peers soon be taking a ramble down the Shambles?

Having re-opened what had seemed to be a firm decision by Parliament, there's a debate today to take the voices, allowing the Commons class of 2019 to give their view.

One strand of that might be to explore the political attraction of shifting a high-profile institution (Their Lordships' House) out of London - but if the idea is to try and reconnect politics with "left behind Britain" why not put it in Sunderland or Newcastle, rather than prosperous York?

Given that 55 per cent of peers live in London, the South East and the East of England, there is indeed a strong case that the Lords is not geographically representative - but is moving the same people to a different city going to change that?

It might shake out a few peers who are unwilling to travel - but it might also usher in more virtual working, allowing the usual suspects to continue to participate from home.

Scrutiny concerns

A deeper question is what such a move would do to the institution.

One of the core functions of Parliament is to scrutinise the government, which is why Parliament is next door to Whitehall and the great departments of state. And one of the lessons of the virtual parliament during the pandemic was that it gave ministers a much easier ride.

Those moments in the chamber where a minister faltered and opinion crystallised against them are much more elusive if the minister is on a screen rather than standing at the dispatch box.

This is not a trivial point - question times with online participants are necessarily more scripted and less searching, and so ministers are not challenged as effectively. Scrutiny suffers if Parliament is physically separated from government.

Awkward territory

So who decides? Theoretically, these are "House Matters" not party matters, to be decided by MPs and peers.

In practice, the government controls the Commons, and if it whips its MPs to back a particular option, it can expect to get its way.

The Restoration and Renewal programme is on the awkward territory between House Matters and the government's completely legitimate concern about a possible bill of several billion pounds, as well as their natural interest in the manner in which they are scrutinised.

But the hard fact remains; however splendid the outward appearance, the Victorian Palace of Westminster is a mess, with dodgy wiring, leaky roofs, cranky (and smelly) plumbing and crumbling stonework.

It could fall down, burn down or flood. Which would be an embarrassing fate for one of the two or three most recognisable buildings on the planet.

- Published19 January 2020