Coronavirus is here. What else should we be worried about?

- Published

Covid-19 is here - but what other dangers are looming?

The government always knew a pandemic was the most serious threat to the UK - more so than terrorism or a huge cyber-attack. So what else should we be worried about?

Anyone who thinks the coronavirus pandemic came as a complete surprise to the UK should read the National Risk Register., external

The little-known Cabinet Office document is effectively a catalogue of the country's worst nightmares. The existential threats detailed across its 71 pages are hard to take in at one sitting.

Solar flares knocking out the communications grid, cyber attacks causing electricity blackouts, terror attacks on crowded places, riots, extreme weather. The list goes on. Each one is graded according to its severity and likelihood.

Since the register was first published in 2008, it has identified a pandemic as the most serious threat facing the country.

The wrong kind of pandemic

In the most recent edition, from 2017, a pandemic is rated as being as deadly as a large-scale nuclear, biological or chemical attack - and more likely too.

Crucially though, the warning is about a flu pandemic, not a new respiratory disease like coronavirus - although some have argued there is little practical difference between the two when it comes to preparing a response.

New infectious diseases, including respiratory infections, are not ignored. They "may become more frequent", notes the register, but the chances of one spreading within the UK is "assessed to be lower than that of a flu pandemic".

Pandemic flu could cause up to 750,000 fatalities in the UK, says the register, while an emerging infectious disease could lead to up to 100 fatalities. Little supporting evidence for these estimates is offered.

It is perhaps no surprise that the new edition of the National Risk Register has been delayed until the lessons of the coronavirus pandemic have been "fully absorbed," according to Cabinet Office minister Lord True., external

Predicting the future is always a thankless task. But serious questions are being asked about whether the government's current risk assessment process is up to the job.

The National Risk Register is just the tip of a very large iceberg and much of the planning for future emergencies goes on in secret.

It is actually based on a classified document, the National Risk Assessment (NRA), meant for official eyes only.

David Alexander, professor of risk and disaster reduction at University College, London, was given a peek at the NRA by a government official a couple of years ago. He says it runs to 300 pages.

"I was allowed to look at three pages of it, with someone looking over my shoulder, but I was told not talk about what I saw."

Prof Alexander questions the need for such secrecy. He argues ministers cannot be properly held to account.

How much money should we waste?

Planning for emergencies means telling political leaders what they don't want to hear - that they will have to spend money they can't afford on preparing for events that probably won't happen.

Emergency planning is all about resources

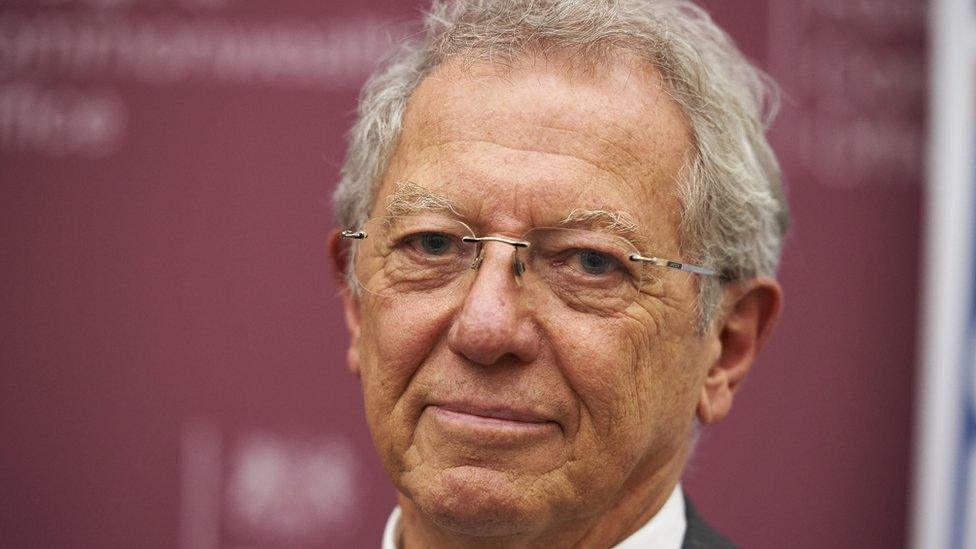

The Astronomer Royal, Lord Rees, who has written two books on the existential threats facing humanity, says attitudes need to change at the top of government.

He cites the example of Tamiflu antiviral medicine, stockpiled by the UK in 2009 at a cost of £473m, for a swine flu pandemic but never used. "The relevant minister was grumbled at, having wasted money stocking up on vaccines. Of course he was quite right to do that."

The peer, who is one of the world's leading astrophysicists, is hopeful that the coronavirus crisis will concentrate minds in government. "What we have got to ensure is that the public encourages them, as it were, to pay an insurance premium," he says.

That still leaves the question of what you insure against, of course.

'A wide variety of experts'

Lord Rees has warned about the need for the risk register, external to look beyond its current five year horizon. There is also concern that it fails to look at the bigger picture.

The register is drawn up, we are assured, by a "wide variety of experts" in government departments, industry, academia and the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The likelihood and severity of the risks are scored by experts on a scale of 0 to 5. The information is passed down to local authorities and agencies to help them plan for the worst.

But the National Risk Register is an internal government process and like all such exercises, it can fall into the trap of putting everything into neat categories.

"It tends to treat risks separately," says Prof Alexander. "[But] what happens when you get a whole slew of risks at once?"

Despite worries, Lord Rees says it is 'hard to imagine anything that could wipe us all out'

This is the doomsday scenario that Lord Rees has spent the past few years warning about. A "cascade of disasters", as he puts it.

"It is hard to imagine anything that could wipe us all out," he says, but a series of catastrophes could "send us back, if not to the Stone Age, then to the Middle Ages or before".

"Maybe a pandemic, which was as fatal as Ebola and as transmissible as Covid 19, spreading worldwide, which would destroy the economy, affect food supplies and general order. That is the kind of thing that could lead to disruption of the social order," he says.

Other scenarios might include an epidemic of cyber attacks, which according to Lord Rees, could mean "modern industry has to be abandoned".

He has also warned of the threat posed by autonomous "killer robots" powered by advanced Artificial Intelligence and the possibility of deadly new infectious diseases being engineered in laboratories by malign forces.

Things we don't worry about any more

And then there those risks that are so crazy that they cannot be predicted. Or risks we don't talk about so much but that haven't gone away, such as nuclear war and the threat of climate change.

Apart from climate change, which falls under the category of a long-term threat, none of these is mentioned in the register.

Only scenarios deemed plausible by government-selected experts make the cut. Disasters must have "at least a one in 20,000 chance of occurring in the UK in the next five years", says the register - although a different system is used for calculating the risk of a terror attack.

There is no mention of asteroid strikes, which were briefly taken seriously by Tony Blair's government, as set out in a 2000 report, external.

Dominic Cummings takes a keen interest in forecasting and emergency planning

So what do we do?

The myriad, interconnected threats facing humanity can only be tackled effectively by international action - but that does not mean we can't do things better in the UK.

Lord Rees has set up a special inquiry in the House of Lords, external into the way the National Risk Register is put together.

"The UK is at risk from a multitude of hazards, some of which could change life as we know it," said Conservative peer Lord Arbuthnot, who is chairing it.

"We need to know what these risks are; we need to prevent what we can; and we need to plan for the arrival of those we cannot prevent."

The committee aims to spend the next year taking evidence from expert witnesses to ensure "to the extent that we can, that our country is protected from any significant harm," he added.

How to handle politicians

The prime minister's closest adviser, Dominic Cummings, also takes a keen interest in forecasting and emergency planning, and has written voluminous blogs on the subject, external.

He believes politicians and civil servants are singularly ill-equipped to understand the risks - and he argues for a more scientifically rigorous, data-driven approach to planning for the future.

Sir David King, who was Tony Blair's chief scientific adviser during the 2001 foot and mouth epidemic, believes government scientists are up to the job. But he says they need to know how to handle politicians.

He launched the Foresight programme, external - still the UK government's main forecasting tool - which has a roving brief to examine future risks, opportunities and emerging trends.

It has examined everything from rising obesity to how artificial intelligence could transform mental health. In 2006, it produced a very prescient report on infectious diseases, external, warning of a pandemic of an acute respiratory illness originating in animals.

Sir David King says climate change is 'the biggest worry of all'

The key to good forecasting, argues Sir David, who also chairs Independent SAGE, a group of scientists set up to critique the government's response to coronavirus, is to get politicians on board at an early stage. Otherwise, he says, "these wonderful reports sit on library shelves and get no response at all".

The scientists need to present a range of scenarios, that don't all involve the imminent collapse of civilization, says Sir David.

He says ministers "get drawn in by the sense of excitement - 'wow let's look at Britain in 50 years' time' - it's a very attractive way to think. We have to project forward to potential gloomy outcomes and climate change is the biggest worry of all.

"But, nevertheless, there is no point in projecting a gloomy outcome if you can't also project a much more satisfactory way forward."

But he is not convinced that the coronavirus crisis will lead to a revolution in planning at the heart of government. The test, he says, will come in the government's response to climate change, which, he argues, dwarfs all other risks in the long term.

'The plan won't work'

In the short term, argues Prof Alexander, the government could make a big difference by paying more attention to emergency planning experts.

Sage and the government's other emergency committees are dominated by medical experts and behavioural scientists, with apparently no room for experts in his field.

He says the first piece of advice he would offer ministers, and what he teaches his students, is that when catastrophe strikes "the plan won't work".

It is about having the correct systems in place - accountable, flexible and robust - to know what to do next.