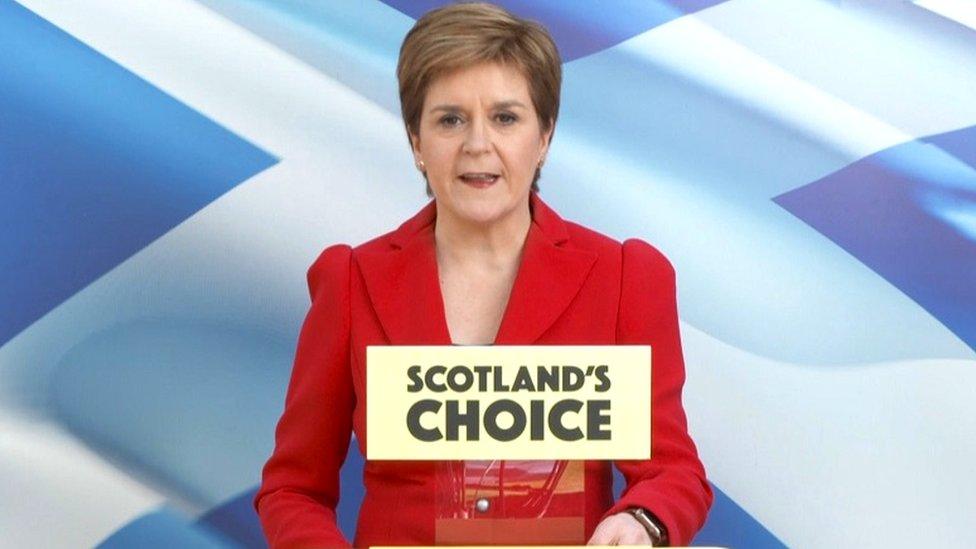

Election 2021: What do the results mean for Scottish independence?

- Published

There is one thing that Nicola Sturgeon and Boris Johnson can agree on. That now isn't the time to have another vote on a Scottish referendum.

That is just about where agreement between arguably the two most dominant political figures in the country right now begins and ends.

Beyond that, the first minister is determined before too long to push for a vote. The prime minister, is set on saying 'no'.

There is one thing they have in common too. They are both vote winners for their parties with big personal followings, who are defying political tradition, refreshing their parties' mandates to govern after over a decade in power.

But if the dispute between them over the future of the UK is ever to be resolved, only one of these winners can come out on top.

From today, Nicola Sturgeon is cranking up her rhetoric, suggesting that Boris Johnson is a democracy denier, set on turning down the desire of what she always terms the people of Scotland, who have expressed their wish for another vote.

Some of her backers, and also some of Mr Johnson's allies, believe that saying a simple blank refusal of another referendum could stoke up support for Scotland going it on its own further.

While she fell short of achieving the high bar of a majority for the SNP on its own, with the Green Party, the Scottish Party does have a majority who want independence.

The SNP is totally dominant in terms of seats. And the parties promising another referendum won. Those parties who vowed to block one lost.

Heading for the courts?

Boris Johnson will resist granting such a vote at all costs, and is keen, for now at least to keep the argument calm.

In his armoury, the legal and technical reality that the law, specifically Schedule 5, Part 1 of the Scotland Act (with which you may get familiar in the coming months, I promise) says in black and white that the constitution is a "reserved matter".

In other words, anything change to how the country is run, or who is in charge is a decision to be made by politicians from all parts of the United Kingdom who occupy the green benches in Parliament.

If you want to take a look for yourself, it's here. , external

Legal experts aren't quite sure however how this would be interpreted in the courts in the rather likely scenario that the situation ends up there one way or another.

Dread or delight

While the first minister has the Parliament on her side, and Boris Johnson has the power and the legal backing as it stands to say no, they both have difficulties too.

Nicola Sturgeon can say the Parliament of Scotland is pro-independence, but she knows very well that its people are almost exactly divided.

As Professor John Curtice, the polling guru explains, "It looks as though the SNP plus the Greens are heading for 49% of the constituency vote, and that the SNP plus the Greens and Alba may win 51% of the list vote.

"In truth, the only safe conclusion one can draw from these results is that Scotland is indeed divided down the middle on the constitutional question."

She has a reliable majority for a referendum in the Parliament, but not when it comes to the public.

The possibility of another referendum delights some voters, but it creates dread for others.

And she will be reminded again and again by unionists that in 2014, she and other figures said the referendum then was a "once in a generation".

Boris Johnson shakes and Nicola Sturgeon in 2019

Conversely, Mr Johnson might find that a flat 'no' to a request from Holyrood proves the SNP's case that the UK government just doesn't listen - that's long been a sentiment that has driven some Scots towards to the case for independence.

And while Downing Street is extremely sure that it doesn't want to grant another referendum, it's less sure how to it can increase support for the union.

The issue has been discussed more regularly than in recent years, there are promises of a new attitude, new spending, and a new focus on proving the case for the UK.

But while there does seem to be a genuine realisation in Tory circles that 'something must be done', quite what, and how compelling it might be, that's still rather vague.

Neither the prime minister, nor the first minister want to join in full battle on this now. But it's a fight delayed, not a fight that's disappeared.

Both successful leaders, both in an uncomfortable status quo, and for that to change, would mean one of them would have to fail.

The politicians who prospered...

P.s. Without question one of the things this complicated set of results has had in common, is that politicians have prospered where they made a big feature of standing up for their areas.

Whether it's Ms Sturgeon's prominent role, and her constant vocabulary about acting for the 'people of Scotland', Andy Burnham's striking words about Manchester, Mark Drakeford in Wales, Ben Houchen in Tees Valley, Andy Street in the West Midlands - the list goes on.

Perhaps, that's down in part to voters rallying behind leaders who have seen them through the pandemic.

Certainly, the emergency has demonstrated more than before the responsibilities that leaders with devolved powers have, and how they can use them.

From a purely political point of view, it's given them a platform.

But there is something else going on perhaps too. Irrespective of party, irrespective of the pandemic, politicians who define themselves against Westminster, who spend time and effort building popularity and profile among their voters are doing well.

Showing up, being visible, and shouting loud on smaller political stages is having an effect on big national results.

As Westminster politicians look on with some envy, we'll return to this theme before too long!

- Published9 May 2021

- Published7 May 2021

- Published9 May 2021