Covid: Test and Trace failure helped Indian variant spread, report says

- Published

- comments

Failures in England's Test and Trace system are partly responsible for a surge in the Indian variant in one of the worst affected parts of the country, a report seen by the BBC says.

For three weeks in April and May, eight local authorities in England did not have access to the full data on positive tests in their area.

The number of missing cases was highest in Blackburn with Darwen, Lancashire.

A recent surge in infections there has been linked to the Indian variant.

The government said a Track and Trace "software issue" had affected a "handful" of places, but this had been resolved "as quickly as possible".

The other areas experiencing incomplete data were Blackpool, York, Bath and North East Somerset, Bristol, North Somerset, Southend-on-Sea and Thurrock.

Labour called on ministers to "explain what's gone wrong".

NHS Test and Trace - for which £37bn has been set aside - identifies people who have been in close contact with someone who has caught Covid.

Between 21 April and 11 May, the system only provided details of a limited number of positive cases of coronavirus to the eight local authorities.

Councils should be able to see Covid data - Jeremy Hunt

On 11 May, they were told by the Department of Health and Social Care that, over that period, 734 positive tests had not been reported.

According to a report by officials at one of the councils affected, the central Test and Trace system failed to notify its staff of cases, meaning their contacts could not be traced locally.

It says that "the rapid spread of Indian variant cases... may be partially or largely attributable to risks in the international travel control system", adding: "These were exacerbated by the sporadic failure of the national Test and Trace system."

Six of the local authorities affected have confirmed to the BBC that they experienced problems.

Although it is thought that the people tested were given their results, local authority staff were not provided with contact-tracing information through the central system.

First contact

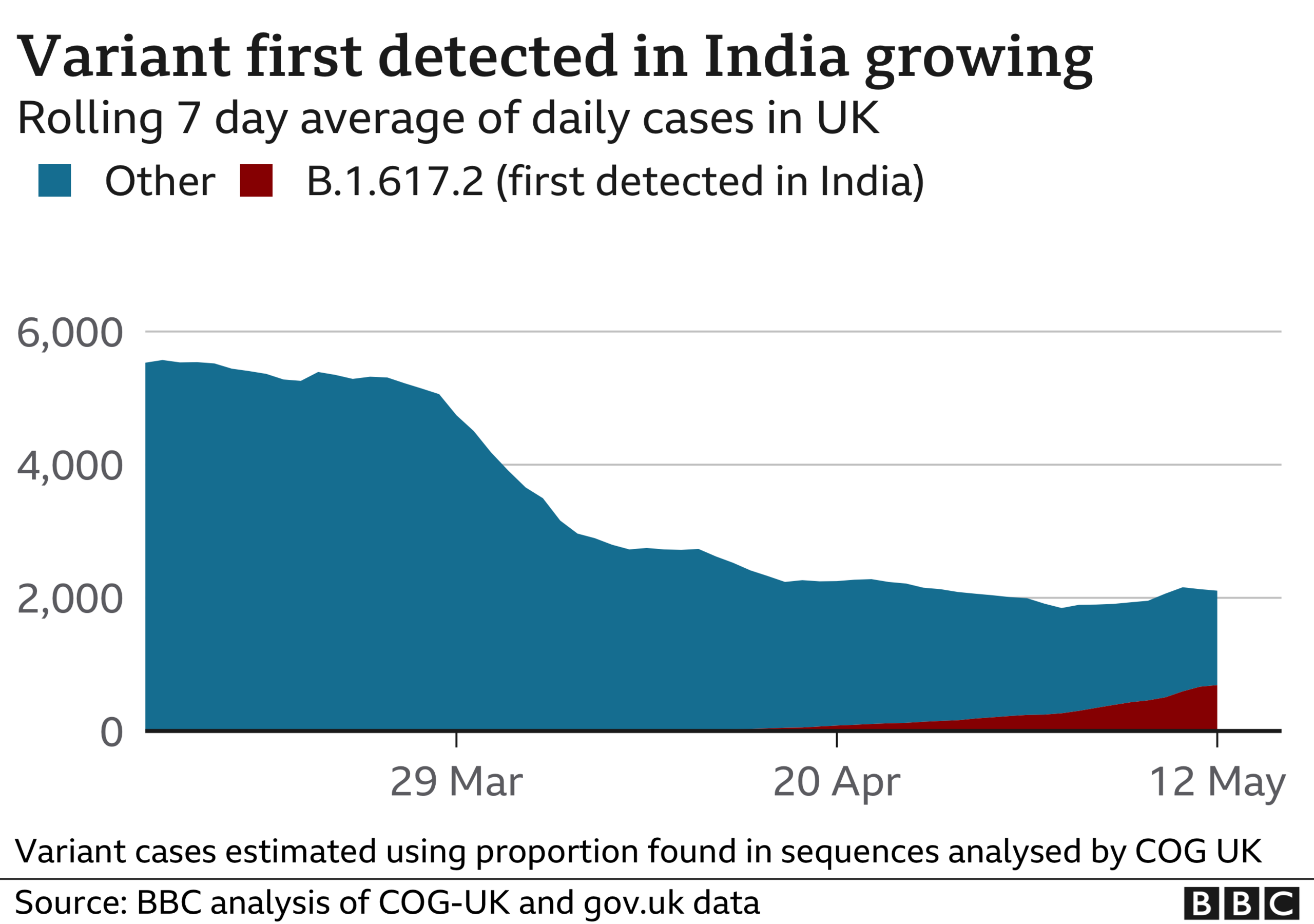

Some 3,424 cases of the Indian variant - which is believed to spread more quickly than the Kent variant that caused the winter spike in infections - have now been identified in the UK.

The government added India to the "red list" of countries, from which travellers must quarantine in a hotel on return, on 23 April - two days after the problems with Test and Trace started.

While national contact-tracing teams should take on variant cases, identifying the particular variant can take up to two weeks.

In the meantime, local authority staff are often the first to make contacts with positive cases.

Where cases went unreported, they were also in many cases unable to offer support to isolating individuals.

The Department of Health told Blackburn with Darwen Council that there were 164 cases it had been unaware of. The people affected were subsequently traced.

Another 130 cases were not reported, but, because they had passed the 10-day isolation period, could not be followed up.

Even when cases were uploaded to the system on 12 May, some key information, such as phone numbers or addresses, was incomplete.

For Labour, shadow health secretary Jonathan Ashworth said it "beggars belief" that councils had been "left in the dark for two weeks when we know acting with speed is vital to containing an outbreak".

He added: "Ministers need to explain what's gone wrong and provide local health directors with all the resources they need to push infections down."

Liberal Democrat MP Layla Moran, chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on coronavirus, said "grave errors" over Test and Trace failures had "contributed to the surge in cases of the Indian variant".

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: "NHS Test and Trace has contacted over 10 million people since the start of the pandemic, and this has had a significant impact, breaking chains of transmission and reducing the spread of the virus.

"Over the past month, we have contacted over 150,000 people to tell them to self-isolate."

The spokesperson added: "Due to a software issue, there was a delay in tracing contacts of a number of cases. This only affected a handful of local authorities and the issue was resolved as quickly as possible."

Data released by Public Health England shows there have now been 3,424 cases of the Indian variant detected - that is up by just over 2,000 on this time last week.

Cases are predominantly affecting the north west of England, particularly Bolton, and London, PHE said.

These numbers are going to continue growing - it is expected the variant will become dominant in the UK as scientists believe it is more infectious than the UK variant.

It's unclear by how much - currently experts are saying it could be anything between 10% to 50% more transmissible.

But what this means for infection levels and, crucially, serious illness remains to be seen.

Overall infection levels remain low. Even if infection levels do rise, there is no guarantee that will translate into significant numbers of hospital cases because of the rollout of the vaccines.

What will be crucial is just how more transmissible it is. Below 25% and the impact on hospital cases is expected to be minimal. Once you get to 40% it could become problematic.

It will be another week until scientists are able to give a confident estimate of what the true figure is.