Coming for Camelot: The battle to land the UK's National Lottery

- Published

Lauren Rowles is worried about the future of the lottery

Camelot - the company that has run the UK's national lottery since it was launched - is in a battle to keep its licence. What is at stake for the millions of us who play the lottery every week and the good causes it funds?

"My generation doesn't play the National Lottery. It's my nan, it's my mum. Those are the people who play the National Lottery."

Like many British athletes, Lauren Rowles, 23, says she would not have reached the top of her chosen field without lottery funding.

But the double gold medal-winning Paralympic rower is not alone in worrying about the future of the lottery.

The transformation of Great Britain from Olympic and Paralympic also-rans to medal table superstars is down, in no small part, to the steady stream of lottery cash that has been funnelled into training and facilities in the past 30 years.

Medal-winning athletes at this summer's Tokyo Paralympics were under strict orders to mention the lottery in post-event interviews.

"You are constantly reminded that the National Lottery funds this," Rowles told a select committee last month.

But, she added, money for elite sport is still "spread thinly" and there is anxiety among athletes about where the lottery goes next and whether funding can keep pace with Britain's international competitors.

Where your lottery money goes

For every £1 of National Lottery ticket sales in 2019/20:

23p to good causes

12p to the government in lottery duty

55p to winners in prizes

4p to ticket retailers

6p retained by Camelot to meet costs and returns to shareholders

1p kept by Camelot in profits

Olympic sport is just one area of national life to have benefited from the £43bn raised for "good causes" since the lottery was launched in 1994.

The biggest chunk of funding - 40% - goes to "community projects", with 20% to the arts, including the British Film Institute, 20% to "heritage" projects, and 20% for sport. These are mostly things that the government can't, or won't, fund from taxes.

Camelot, which has run the lottery since it was launched in 1994, has nothing to do with the way the money is parcelled out. It is purely concerned with devising the games, selling the tickets and awarding prizes. It likes to boast that it has created more than 6,000 millionaires.

But the lottery giant, which is owned by a Canadian teachers' pension fund, has not done too badly out of it either, even though it is only allowed to keep 1% of the money generated from players.

In the year to March 2021, it made a pre-tax profit of £95.2m, external on sales of £8.4bn (the good causes got £1.8bn).

Little wonder that the contest for the fourth 10-year lottery licence has reportedly been fierce.

But because it has been held behind closed doors by the Gambling Commission, which is not commenting on the process, it is difficult to assess what Camelot's three rivals would do differently. The winner will be announced in early 2022.

Here is what we know about the challengers:

Allwyn

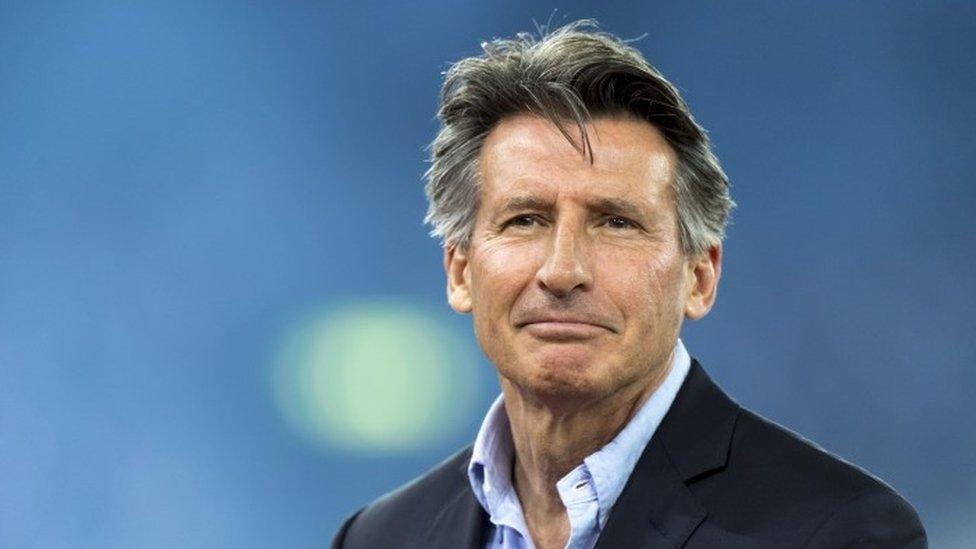

Lord Coe is advising Europe's largest lottery operator

Europe's largest lottery operator Sazka - owned by Czech oil and gas tycoon Karel Komarek - signalled its intent earlier this year by launching a UK-based subsidiary, Allwyn, to front its National Lottery bid.

It has raided the London 2012 Olympics organising committee, including Lord Coe and entrepreneur Sir Keith Mills, to sit on its advisory board, and claims to be "ahead of the curve" on using technology to breathe new life into the lottery.

Sisal

Lady Brady is one of Sisal's star signings

The Italian lottery operator has also assembled a well-connected team of advisors, including Lady Brady, of Apprentice and West Ham football club fame, and fellow Tory peer Lord Vaizey, the former culture minister.

It has announced a partnership with children's charity Barnardo's and telecoms giant BT, with the aim of using new technology to widen the appeal of games.

Northern and Shell

Richard Desmond has vowed to bring the lottery "back into British hands"

Former Daily Express owner Richard Desmond is already a big name in the UK lottery business.

His Northern and Shell empire is behind the Health Lottery, which was launched in 2011. To avoid falling foul of the Gambling Act, which allows just one national lottery, it is organised as 12 regional draws, with 20% of takings going to local health-related causes.

Desmond has accused Camelot of losing its way and vowed to bring the National Lottery "back into British hands".

Camelot's track record

Camelot, which has seen off previous challengers, including Richard Branson's People's Lottery, claims to run one of the most efficient and robust lotteries in Europe.

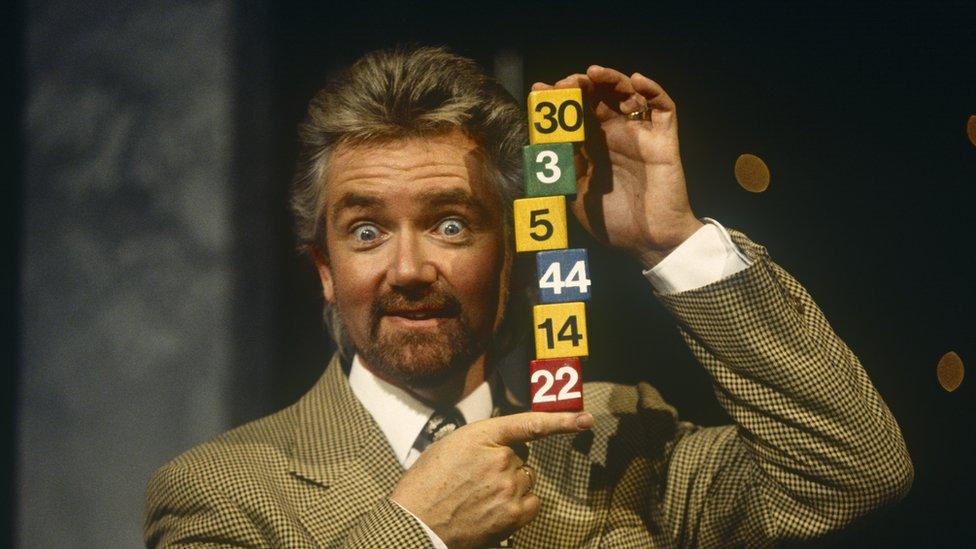

Noel Edmonds hosted the first National Lottery draw in 1994

It says it wants to offer "something for everyone", with people able to access games on any device.

Its rivals have accused it of allowing the lottery to stagnate, by relying too much on a slowly dwindling cohort of older players. The excitement and novelty value of the weekly lottery draw is long gone, and it disappeared from our TV screens in 2017.

Camelot has responded to declining sales by launching new products, such as Euromillions, with huge rollover jackpots, and Set for Life. where players can win £10,000 a month for 30 years.

It has also sought out new markets with scratchcards and online instant win games, which give players a much greater chance of winning small amounts of cash.

These games have proved popular, but because more money is handed out in prizes, a smaller percentage of the ticket price goes to good causes.

Winning the Euromillions jackpot can change your life

In 2018, MPs on the Public Accounts Committee were highly critical of Camelot for increasing its funding to good causes by 2% between 2009-10 and 2016-17, while its profits had increased by 122%.

The company has taken steps to reduce the gap, but the next lottery licence, which starts in 2023, will force the operator to keep profit growth in line with donations.

Do we need a lottery at all?

Camelot has always maintained that the main lotto draw is more about funding good causes than gambling. The odds would seem to bear that argument out.

The chances of winning are 1 in 45,057,474. In other words, it could be you, but it almost certainly won't be.

You stand a much better chance of winning a few quid with a scratchcard or online draws, but critics say the instant hit provided by these games can fuel gambling addiction, particularly among young people.

Camelot has responded to these concerns by raising the minimum age of lottery players from 16 to 18 and tweaking some its games to make them less attractive to potential problem gamblers.

The athletes giving evidence last month to the select committee were pragmatic about the role the lottery has played in their lives.

Adam Peaty bagged another gold medal at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

Olympic swimmer Adam Peaty, who no longer relies on lottery funding, said it had given people like him, from working class backgrounds, an invaluable leg-up, but it was no substitute for proper government funding of grassroots sport.

Some of the MPs on the committee could not hide their distaste for lottery cash.

The SNP's John Nicholson told the athletes: "I was very uncomfortable when I heard that you had to pay homage to greedy Camelot, the fact that you're instructed to be obsequious to them on camera.

"It made me feel terribly uncomfortable because at the end of the day, this is funded by gambling."

The National Lottery is clearly here to stay, but for some it will always be an immoral enterprise, a tax on the unrealistic dreams of the less well-off.

The companies vying for the next licence will be under pressure to show how they will protect vulnerable players.

But, at the same time, they are also competing to inject fresh excitement into the games, to generate more cash for the causes, and, of course, themselves.