No breakthrough in 'tetchy' Northern Ireland Protocol talks

- Published

- comments

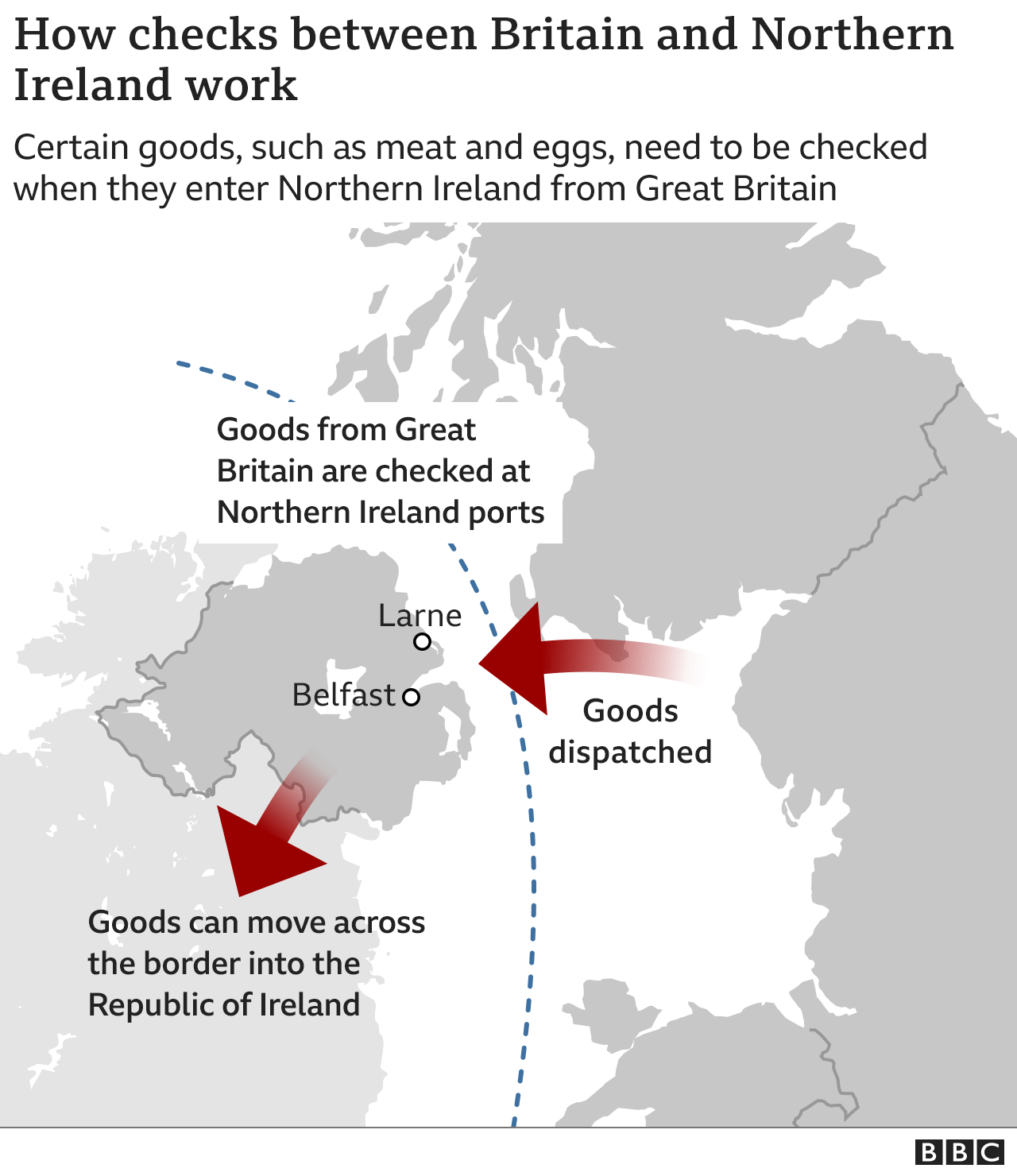

The protocol imposes checks on goods between Britain and Northern Ireland, which angered unionists

The foreign secretary has warned the UK will have "no choice but to act" if the EU does not show enough "flexibility" over post-Brexit checks on goods going from Britain to Northern Ireland.

A call between Liz Truss and the EU's Maros Sefcovic was termed "tetchy".

New legal advice to the government has suggested it would be lawful to override parts of the arrangements, known as the Northern Ireland Protocol.

The EU has warned it could retaliate by introducing trade sanctions.

Following last week's elections to the Northern Ireland Assembly, the DUP are refusing to enter a new power-sharing administration with Sinn Fein unless there are significant changes to the protocol, which governs trading arrangements with the EU after Brexit.

On Thursday morning, Ms Truss spoke to European Commission vice president Mr Sefcovic.

The Foreign Office said Ms Truss said the UK's "overriding priority" was to protect peace and stability in Northern Ireland, and the protocol had become "the greatest obstacle" to forming a new executive at Stormont.

The UK said Mr Sefcovic had again insisted there was "no room to expand the EU negotiating mandate or introduce new proposals to reduce the overall level of trade friction".

'Not acceptable'

In a statement, Mr Sefcovic said the UK's threat of "unilateral action" was "simply not acceptable".

He said Brussels had put forward wide-ranging solutions that would "substantially improve the way the protocol is implemented".

And he warned that acting unilaterally would "undermine the conditions which are essential for Northern Ireland to continue to have access to the EU single market for goods".

Asked later if the wording of the protocol needed to be changed, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said the institutions of democracy in Northern Ireland had collapsed.

He said that was because the unionist community would not accept the way the protocol was working, adding: "We've got to fix that."

Downing Street said Brussels' position was "disappointing", but no decisions had been taken on the government's next steps.

"We will continue to see what, if any, progress can be made," No 10 added.

So what now?

Essentially UK ministers need to make up their minds.

Liz Truss is said to be among the more hard-line cabinet ministers on this matter. Her allies say she is genuinely frustrated by what London sees as EU intransigence.

Remember, she started off by trying to charm the Commission's Maros Sefcovic at her grace and favour mansion in Chevening. Months later, with little progress, Brussels suspects Britain is reverting to hardball.

EU diplomats are also quick to point out that this agreement was one that Boris Johnson's government signed just over two years ago.

I understand that if the UK does go ahead with legislative plans to try and scrap parts of the protocol, the government doesn't regard it as a cut off point for talks.

The legislation, I'm told, could take the best part of a year.

That's something that Brussels is well aware of and its infringement proceedings may likewise be slow-burn.

So it's possible the talks continue but with even higher stakes if they still can't agree.

The Northern Ireland Protocol has been a contentious element of the Brexit treaty, signed by the UK and the EU in December 2020.

The arrangements were designed to avoid the need for a hard border with the Irish Republic - which remains part of the EU - and customs checks on that frontier after Brexit.

Many believed that could have threatened the peace in Northern Ireland ushered in by the Good Friday Agreement.

But unionists argue the protocol created a border in the Irish Sea instead, causing Northern Ireland to be treated differently from the rest of the UK.

The EU proposed changes to the protocol in October, focused on reducing inspections of food products in particular, but Ms Truss has rejected this plan.

Because of grace periods, the protocol is not yet being fully implemented, so the UK has argued that the changes being put forward would actually increase checks and controls, leading to "everyday items disappearing from the shelves".

Mr Sefcovic has previously called on the UK to "dial down the rhetoric" and to "be honest" about what it committed to when it signed up to the protocol.

The Times, which first reported the change in legal advice, external, said the attorney general argued that signs of violence - such as a hoax bomb attack targeting Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney in March - justified the UK overriding the deal to keep the peace.

Asked about the possibility of a trade war, Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney said Brussels wanted a compromise, but warned the EU could not ignore a breach of international law.

At the moment it's not clear what the government intends to do: trigger Article 16 or something more dramatic?

Article 16 is part of the Northern Ireland Protocol and allows either party to suspend parts of the deal if it's causing serious problems.

Some of what has been briefed by the government sounds like they have taken legal advice on Article 16; phrases like "diversion of trade" and "societal difficulties" refer directly to justifications for using Article 16.

But the Times story also refers to legislation, external which would "scrap" or "override" the protocol.

If the government is going down a separate legislative route to remove parts of the protocol in UK law, it's not clear why they would bother sounding out justifications for Article 16.

Not using Article 16 would be a bigger step as it would involve stepping well outside the bounds of the deal and be seen by the EU as a breach of the treaty and of international law.

A few months ago, the idea was floated that Article 16 could be used alongside domestic legislation which could provide legal clarity to business.

Perhaps that's back in the agenda.

A stand-off over the issue has emerged from last week's Northern Ireland Assembly elections.

The Democratic Unionist Party - which came second in the poll behind Sinn Féin and backs continuing the union between Great Britain and Northern Ireland - is refusing to nominate ministers to help form a new executive until its issues with the trade protocol are tackled.

The election established a majority for assembly members who support the protocol, with the republican party Sinn Féin as the largest party for the first time.

But under the rules of the Northern Ireland Assembly, Sinn Féin cannot nominate a first minister without a unionist deputy minister.

THE DARK SIDE OF FIGURE SKATING: How enormous pressure can lead young skaters to eating disorders

FROM WILD GARLIC PESTO TO RISOTTO PRIMAVERA: 20 delicious recipes for the perfect spring feast

- Published10 May 2022

- Published11 May 2022

- Published9 May 2022

- Published9 May 2022

- Published13 October 2021