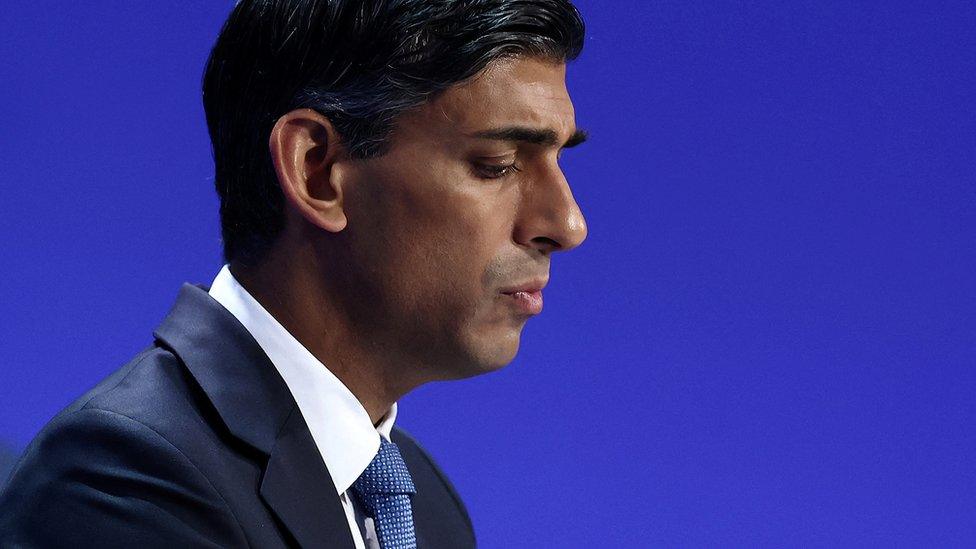

Chris Mason: Rishi Sunak is in a bind over inflation

- Published

- comments

"It's on me personally" if inflation isn't halved this year, Rishi Sunak said earlier this month.

No 10 has now described the promise as an "ambitious target" which they "remain committed to".

The economic and political consequences of inflation that is both high and seemingly wedged high are broad.

As interest rates rise to try to drag the rate of price rises down, the desire from some for government help to ameliorate the impact on people grows.

It is a clamour magnified by recent precedent - the colossal state interventions during the pandemic and after the energy price spikes caused by Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

"The thing is they were black swan events, they came out of nowhere, were a massive surprise and we were right to do something big. But you can't do that when interest rates go up to deal with inflation," one minister said to me.

And, ministers add, both privately in candid terms and publicly rather more carefully, it would be counterproductive anyway: it wouldn't help squash inflation.

In other words, what a bind.

All of which has been tempting me into the archive.

'If the policy isn't hurting...'

Let me take you to Northampton, in October 1989. It's for a speech by the chancellor at the time, John Major., external

You can easily imagine some of his words then being used by Jeremy Hunt, the current chancellor, now.

"The problem is inflation. I have no doubt that the central task before us is the reduction and the elimination of rising prices. Not only does this objective remain the same, but so do the policies needed to achieve it," Sir John said, in what was his first speech as chancellor.

But he was also rather more blunt than today's generation of politicians are usually willing to be.

He also said: "I understand the difficulties that many face with high interest and mortgage rates. But they - and the resulting slowing of the economy that we must see - are the means by which we will cure the problem. They are not the problem."

And he added: "So inflation must go. Ending it cannot be painless. The harsh truth is that if the policy isn't hurting, it isn't working."

As chancellor, John Major gave the public a blunt message on inflation

Sir John spoke then, very candidly, about a timeless economic and political trade-off, between inflation and interest rates.

Granted interest rates were then under the direct control of the government. They are now decided by the independent Bank of England, which is tasked with keeping to an inflation target set by the government.

Knee-jerk instinct

But the trade-offs remain and privately, ministers acknowledge that. And if interest rates go too high, the risk is a recession, a year or so out from a general election.

One minister told me that interest rates had been close to zero for so long that people had collectively forgotten that that couldn't possibly last forever.

Another added that it was about time that savers could get some returns on their savings, even if, for now at least, those returns remain below inflation.

Plenty I speak to in government privately are exasperated by what they see as a knee-jerk instinct for government intervention, including from some on their own side.

But politicians can never be blind to the public mood - and the realities of economic pain.

The chancellor will meet mortgage providers later this week and we can expect to hear from the prime minister on all this again too.

Labour has set out its approach. The Liberal Democrats want a Mortgage Protection Fund to help homeowners on the lowest incomes.

Oh and one final thought: Rising interest rates have an impact too on the biggest borrower of all: this government, and its successors.

That rising cost of borrowing will affect millions of households. But it will also affect what political parties conclude is affordable for them to promise.

And what is not.

Sign up for our UK morning newsletter and get BBC News in your inbox.

Related topics

- Published21 June 2023

- Published21 June 2023