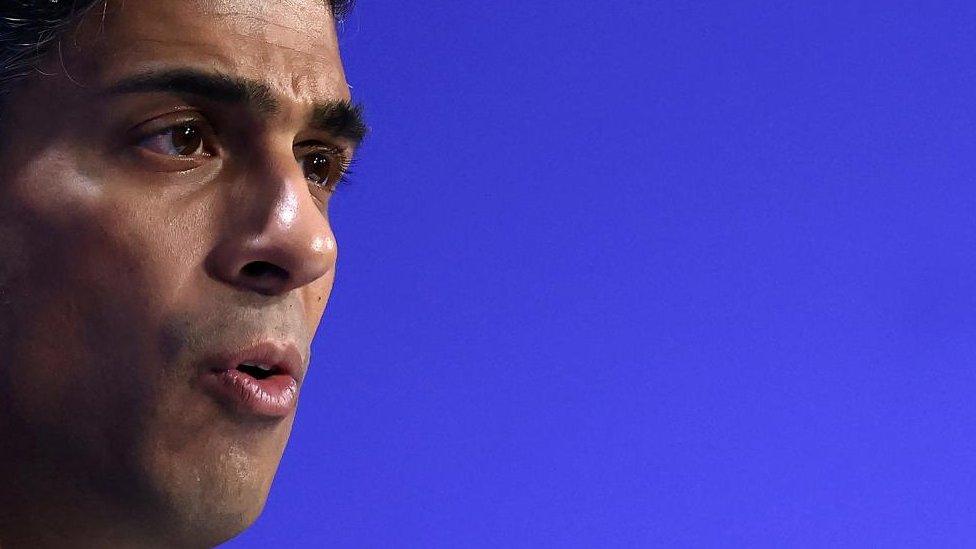

What can Rishi Sunak do to tackle inflation?

- Published

- comments

"Halving inflation this year" is one of the prime minister's top five priorities.

It's currently stuck at 8.7%.

When Rishi Sunak is asked how he'll meet his goal, he points to raising interest rates.

Something the Bank of England, not the government, controls.

The truth is there are some short-term levers government could pull.

The problem is they - as well as interest rates - all involve unpalatable political choices.

Interest rates

The Bank of England and government's argument for hiking interest rates - which some economists dispute - is that it makes borrowing more expensive.

That means people and businesses have less disposable income, less ability and incentive to spend, which pushes down the demand for goods and services.

If there's less demand for something, or more of it, the price usually goes down.

The downside of raising interest rates is it inflicts financial pain on anyone with loans, mortgages or credit card debt.

It means government debt, which is paid off by our taxes, also becomes a lot more expensive.

Raising interest rates also doesn't impact everybody equally - and so the impact on inflation is staggered.

ONS data, external shows more households own their home outright (37%) than with a mortgage or loan (26%).

So that 37% won't have less cash to spend.

Any of the 26% who are on a fixed rate mortgage that isn't up for renewal won't be hit just yet either.

The rest of the population privately rent, or are in social rent, so could well end up spending less due to rising rents.

Balancing act

Another question around rising interest rates is what it means for Rishi Sunak's second priority: growing the economy?

The strategy to get inflation down relies on stopping people from spending as much.

What does that mean for businesses? If people spend less in businesses, what does that mean for jobs? If people end up out of work, what does that mean for the government's welfare bill? And, therefore, for that third priority of the prime minister's: reducing national debt.

The increased cost of borrowing from high interest rates can also disincentivise investment in business, which can also lead to lower economic growth.

The tricky balancing act between inflation and recession is getting worse.

So what is in the government's power?

Taxes and spending

One quick lever the government can pull is taxes.

Raising taxes is another way to stop groups of people from spending more.

But that's an unpalatable political choice too.

Mr Sunak has previously made it clear, and pledged in the past, that he wants to cut - not raise - taxes before the next election.

Some Tory MPs have been repeatedly calling for tax cuts.

Governments can also reduce spending.

While we do hear ministers talk about making "efficiencies", departments talking about making cuts is - again - an unpalatable narrative ahead of an election.

Mr Sunak has said, for now, that he wants to make sure government is "responsible" with borrowing.

Another quick lever would be price controls - the government setting limits on price increases.

Mr Sunak says ministers are "looking at" supermarkets to make sure they are behaving responsibly, for example.

But Number 10 have been clear they are not introducing price caps and any such schemes would be at retailers' discretion.

Wages

The governor of the Bank of England has suggested workers shouldn't ask for excessive pay rises.

The government has also been very reluctant to hike public sector wages, especially if funded by more borrowing.

Both argue giving people more money in their pockets could fuel inflation: if people's wages keep up with rising prices, they can buy the same things, so demand (and prices) remain similar.

In blunter terms - their strategy of reducing inflation by reducing demand means people need to be able to afford less.

This argument has led to strikes in multiple sectors, with unions arguing this is unfair for workers.

Watch: Sunak makes five pledges on the NHS, economy and migrants

This is also a tricky balancing act here for the economy.

If people can afford less: what does that mean for growing the economy? And jobs?

Potentially putting people out of work has a government price tag too.

Supply

So what about pushing supply up, rather than demand down, to lower prices?

Supply-side reforms are, in simple terms, decisions that could make industries more productive to increase the supply of goods and services - and grow the economy too.

Free-market examples include things like cutting business taxes, regulation, red tape, or even certain worker protections or welfare benefits. Or increasing migration for certain sectors.

State-intervention examples could be building more houses, investing in infrastructure, or investing in homegrown energy supplies like nuclear power or renewables.

Clearly, any of these involve political choices too.

But they also take time to come into effect.

In short...

The government - and Labour - have ruled out direct support to help people with mortgages, saying this would fuel inflation - and instead point to existing benefits for the most vulnerable.

Ministers are continuing to point to interest rates as the solution, though most are reluctant to admit that involves a lot of pain for it to work.

It's important to remember when the government says it can't do something that what they're usually referring to is a choice.

Each choice comes with its own shade of political thorniness, and potentially means trading the prime minister's priorities off against each other.

Related topics

- Published21 June 2023