Poor quality university courses face limits on student numbers

- Published

- comments

The OfS says nearly three-in-10 graduates do not progress to highly-skilled jobs or further study 15 months after graduating

Universities in England could be restricted in recruiting students to poor quality courses, under new government plans.

Ministers will ask the independent regulator to limit numbers on courses that do not have "good outcomes".

Education Minister Robert Halfon said imposing restrictions would encourage universities to improve course quality.

Labour said the move would "put up fresh barriers to opportunity in areas with fewer graduate jobs".

The advocacy group Universities UK said university was a great investment for the vast majority of students.

A spokeswoman for the organisation warned any measures must be "targeted and proportionate, and not a sledgehammer to crack a nut".

Are you a student or recent graduate with a view on this story? Get in touch.

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803, external

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

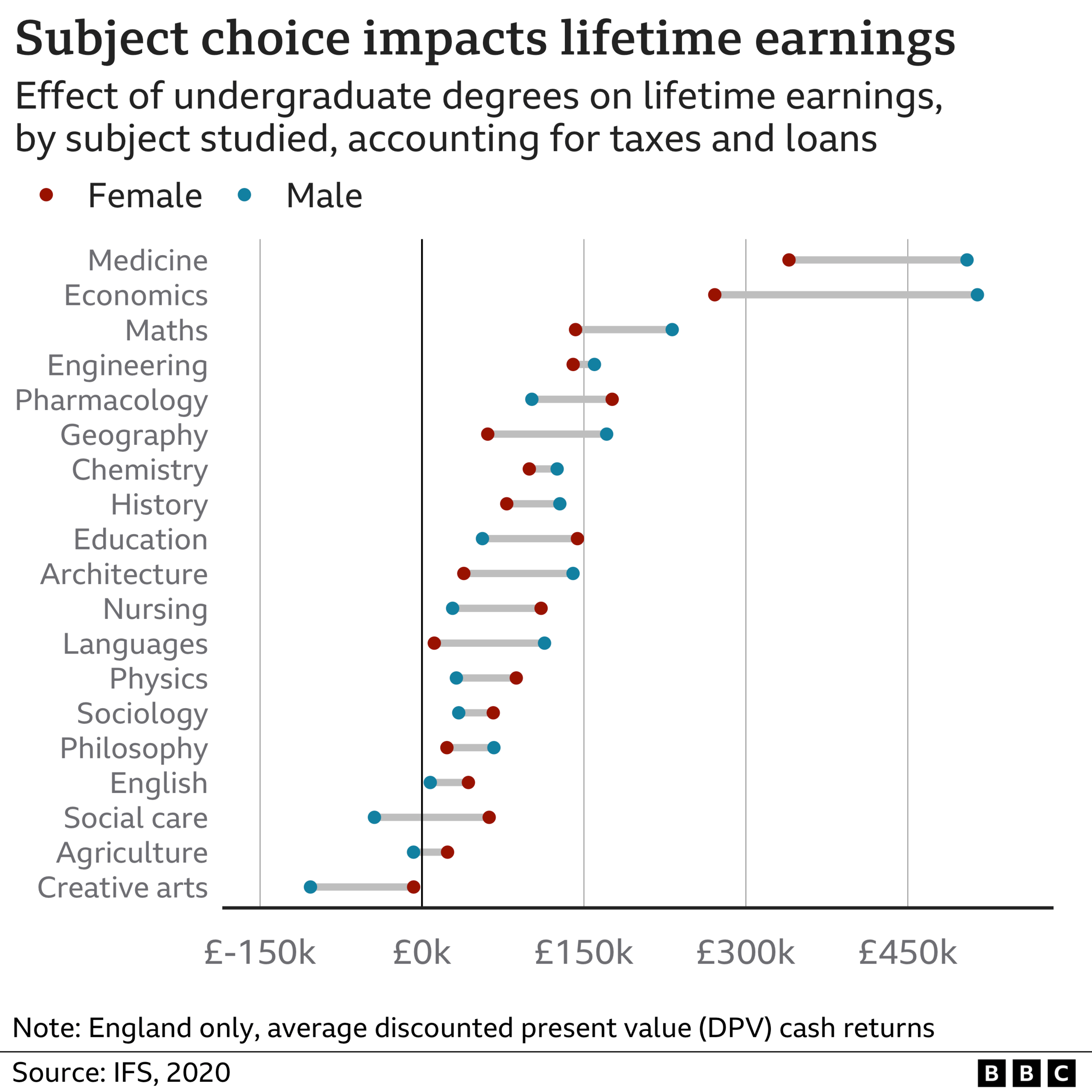

The government said courses that do not have "good outcomes" for students would include those that have high drop-out rates or have a low proportion of students going on to professional jobs. It will also look at potential earnings when deciding if a degree offers enough value.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said: "The UK is home to some of the best universities in the world and studying for a degree can be immensely rewarding. But too many young people are being sold a false dream and end up doing a poor-quality course at the taxpayers' expense that doesn't offer the prospect of a decent job at the end of it."

Nearly three-in-10 graduates do not progress into highly-skilled jobs or further study 15 months after graduating, according to the regulator, the Office for Students (OfS).

The OfS already has the power to investigate and sanction universities in England which offer degrees falling below minimum performance thresholds - but the new rules would permit the regulator to limit student numbers for those courses.

The current thresholds for full-time students doing a first degree are for:

80% of students to continue their studies

75% of students to complete their course

60% of students to go on to further study, professional work, or other positive outcomes, within 15 months of graduating.

This announcement does not change these criteria, and other aspects of the policy are unclear, such as how many students may be denied a place at university in future and which subjects would be most affected.

The Department for Education would not say which courses would be at risk of recruitment limits as this would be for the OfS to determine.

Speaking on Radio 4's Today programme, Education Minister Mr Halfon said putting limits on underperforming degrees would mean those courses "will then improve".

"Students will be able to make informed choices," he said. "If a course has poor outcomes they might choose to do another course at university, they may still decide to do that course but will have the recruitment limits on it."

He suggested the OfS would use "existing powers" to look into poor quality courses, saying: "We can't order the Office for Students to do anything."

Labour's shadow education secretary Bridget Phillipson said the announcement was "an attack on the aspirations of young people".

Rishi Sunak says apprenticeships are an “equally high alternative to universities”.

But Mr Halfon dubbed that accusation as "nonsense".

"The Labour party has been obsessed with quantity over quality and had been party of poor standards in education," he said.

Liberal Democrat education spokesperson Munira Wilson said the prime minister was "out of ideas" and had "dug up a policy the Conservatives announced and then unannounced twice over".

She said: "Universities don't want this. It's a cap on aspiration, making it harder for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds to go on to further study."

Universities UK said the UK had the highest completion rates of any OECD country and overall satisfaction rates were high.

"However, it is right that the regulatory framework is there as a backstop to protect student interests in the very small proportion of instances where quality needs to be improved," a spokeswoman said.

The idea originated in a 2018 review set up under then-Prime Minister Theresa May. The same review also suggested that more money needed to be pumped into education and that tuition fees needed to be cut - but these are not being implemented.

The new pledge comes ahead of three by-elections in Conservative-held seats on Thursday.

The government also announced it would reduce the maximum fees universities in England can charge for classroom-based foundation-year courses, from £9,250 to £5,760. In 2021/22, 29,080 students across the UK were studying a foundation degree.

Foundation year courses are designed to help prepare students for degrees with specific entry requirements or knowledge, such as medicine and veterinary sciences.

However, the government said research suggested too many people were encouraged to take a foundation year in some subjects like business, where it was not necessary.

University Alliance, which represents professional and technical universities, said cutting fees for foundation year courses was "disappointingly regressive" and "makes them financially unviable to deliver".

Chief executive Vanessa Wilson said: "Disadvantaged students and the 'Covid generation' will lose out if this provision is reduced or lost."

She added that the government had chosen "to berate one of the few UK sectors which is genuinely world-leading".

Update 28 July 2023: This article was amended to make clear government plans apply to universities in England only.

Related topics

- Published20 April 2023

- Published1 July 2020